The Free Press

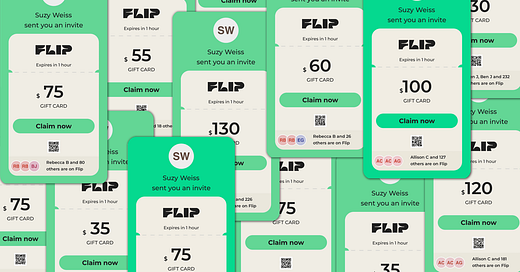

It started a few weeks ago. Texts from friends, and then acquaintances, with a coupon for $120 and a simple declaration: “Add me on Flip.”

I scoffed. “What is this?” I texted back. “Have you been hacked?”

Eventually I clicked and was taken to a site called Flip, where I read that it was “For the stories told over transactions.”

“For everyone who understands that shopping is not just about acquiring, but about coming together,” it read.

Then I was not only confused but disturbed.

I noticed a Flip fever taking hold of The Free Press offices. Everyone under 35 told me they were on the site, scrolling and scoring anything from skincare to lamps. A co-worker offered, “It’s like TikTok for shopping.”

Flip’s app launched in 2021 and they’ve since secured nearly $95 million in venture funding, including cash from the sovereign wealth fund of Abu Dhabi. It’s climbed the charts to number fifteen in the shopping category of Apple’s app store with some 2 million users. To get people to sign up, Flip awards users a credit of up to $140 for each new friend lured onto the site. (The more contacts a friend already has on Flip, the more credit they’re worth.) If you bag a friend, you both get a windfall to spend in-app.

The total amount you rake in is limited only by the number of contacts you have. Flip shows me that if I got everyone in my contacts list to sign up, I’d get $40,730 in credit. It’s like a Ponzi scheme except, it seems, we’re all just spending Abu Dhabi’s money.

On the app are thousands of brands including home goods, accessories, and every cosmetic item you can think of. There are clothes, there are gadgets. There’s endless crap for your pet.

Ten evenings ago, a friend, Rebecca, sent me yet another invite. “Everyone is texting me this!” I responded. “Is it a Ponzi scheme?”

“Hope not,” she texted back. I cracked, and clicked the little card Rebecca sent me, and was whisked to the app store, where I downloaded Flip, and set up an account.

And that’s where the trouble starts. Once you’ve impatiently agreed to give away your data, access to your camera roll, your location, who knows, who cares, you’re delivered to the Flip feed. There you encounter video after video of mostly women, your new “Flip Fam,” trying out a new product—a stainless steel saucier, a gel eyeliner pencil, tweezers, a rice cooker, blush, workout clothes, a bergamot candle, an anti-anxiety journal—behind a banner where you can click to buy it.

The people in the videos are mostly not professional influencers whose job it is to project an aspirational lifestyle and sell product placement on their feed. But they’ve spent so much time watching influencers hawking wares they’re able to regurgitate the ubiquitous technique on demand.

“Hi guys,” an off-screen voice will purr, doing her best Kim Kardashian, steadying the camera while she burglarizes a cardboard box. “I’m super excited to show you my new bedsheets from Sheets & Giggles in the color lilac.” If a Flip user buys those sheets through her video, the creator earns even more money to spend on Flip. (You also accrue rewards for just viewing and interacting with content. Reviews are usually summed up with “obsessed.”)

And on and on it goes; an ouroboros of stuff, a perfect and terrifying infinity of advertisements whose by-product is content and packaging. The whole thing would give Marshall McLuhan a headache. It gave me a cookie sheet, three skin serums, kitchen shears, and a serving spoon. Within a day, I was sending out my own invitations, begging people to sign up with my code. So was everyone else, it felt like.

“Add me on Flip,” I implored a high school classmate who I hadn’t spoken to in a decade. I texted invitations to exes. I offered my code to someone only to sheepishly follow up with “Also, happy birthday.” I was chasing the high of more credits, pestering friends to spend theirs so I’d get mine, the $40,000 constantly blinking in neon somewhere in my imagination.

The app founders clearly believe—and maybe they’re right—that this is the future of shopping.

But really, it’s the past.

In the early aughts, I used to watch QVC on my grandmother’s television while she slept, that channel where the commercial is the whole show. You’d listen to the coiffed ladies go on and on about Tupperware or sterling silver jewelry or limited-edition Beanie Babies. They’d spend hours pointing out observable facts about the products like, “This Tupperware is a little smaller than that one, for snacks.” The joke, of course, was on the customer, who’d slowly become convinced that not only should they buy the product being sold, but that they deserved it. That they earned it. That it would change everything.

Like with all social media, Flip—and in this case, QVC—eliminates the middleman. The shopper becomes the reviewer, saleswoman, and advertiser all at once, fused into a single over-incentivized being who only ever wanted free charcoal toothpaste but ended up with a new set of silverware. Flip understands that in the digital age, shopping online and “adding to cart” is where the adrenaline rush comes in. Especially if you think you’re getting a deal.

As a journalist, I cannot be bought. But as a private citizen, I will fork over my entire contact list for $35 in credit. And apparently my Saturday night, which I spent ferociously clicking through the various brands on Flip to assure myself I was spending my free money wisely. I scrolled until my eyes crossed and my thumb hurt. A friend and I joked about Flip Wrist—carpal tunnel from hours of swiping. We fantasized about saving up all our credits from our contacts to buy a house.

According to its site, Flip is for people whose “standards are serious,” as if it’s an advanced condition. And it is. By the time you place your order for the thing you didn’t need, the upgrade you’d never really thought about, you’ve already bookmarked eighty other products on your wishlist. My Flip Fam—which includes an eight-year-old who exclaimed about a mascara,“It’s gluten free and vegan!”—reminds me that this is a form of self-care. That I deserve this. That this will change everything.

By now it’s been a week and the Flip boxes are arriving. The cookie sheet was tiny, basically built to fit an Easy-Bake Oven. A co-worker’s electric kettle had dead spiders rolling around in it. Luckily for us, Flip does free returns.

Suzy Weiss is a Free Press writer. Read her last piece about the people who race 3,100 miles in 52 days to achieve world peace, and follow her on Twitter (now X) @SnoozyWeiss.

Kiran Sampath contributed to the reporting of this story.

Subscribe to The Free Press today:

We would laugh at my mother-in-law who got boxes from QVC every day. Now, we see boxes from Amazon everyday and wonder "what's the difference?" Am going to avoid this Flip craze as long as possible!

I laughed so much at this, thanks, and hard pass.