Opening Day is here, ushering in another season of America’s so-called national pastime.

Across the country, fans will don their jerseys, munch on overpriced hot dogs, and settle in for nine innings of what is—depending on who you ask—either poetry in motion or an excruciating slog.

For some, the sport elevates simple things, like throwing, hitting, and catching, to something close to a religion. For others, it’s a snoozefest out of step with an era of shortening attention spans that lacks the drama of football or basketball.

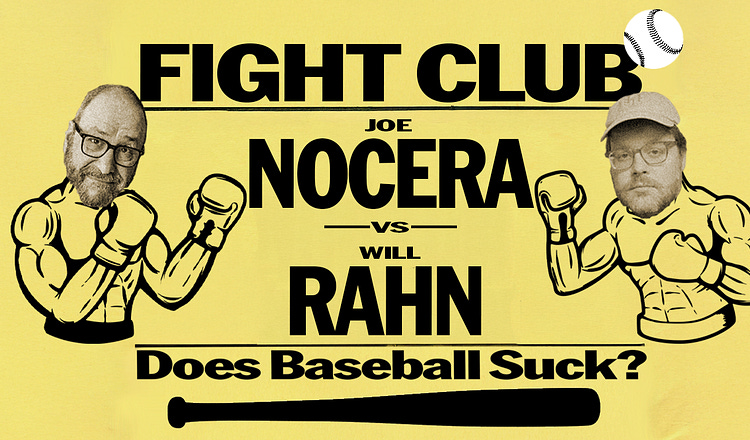

The benches were cleared over this question in The Free Press newsroom recently. And so we decided to settle things with a special Opening Day installment of Free Press Fight Club. Will Rahn believes that baseball is unlike any other sport—a transcendental experience, filled with drama, heartbreak and, occasionally, a miracle or two. Joe Nocera argues that the games are too slow, the richest teams too dominant, and that reforms to fix the sport are too little, too late.

So—does baseball deserve to be a national treasure, or should it go the way of rotary phones and dial-up internet? Play ball!

—The Editors

Stepping up to the plate first, Will Rahn:

Baseball is like love in that it’s essentially impossible to say something new about it. The crack of the bat, the smell of the field—that’s all been covered at length. Great writers, for whatever reason, tend to love baseball. Maybe it’s the rhythm, the slower pace that lets the mind wander. Watching a baseball game is a form of meditation—albeit one you hope will be interrupted by hugs and cheering and high-fiving strangers.