The Free Press

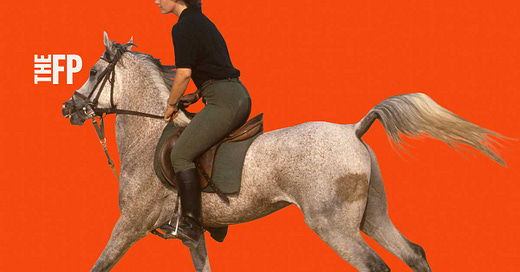

Welcome back to our summer series, “What School Didn’t Teach Us,” where six writers—one for each day this week (except Sunday, that’s Douglas’s day)—share the lessons they’ve learned outside of formal education. Yesterday, Kat Rosenfield explained why Gen Z should loosen up and discover the joys of alcohol. Today, Larissa Phillips—who you might remember from her piece, “What City Kids Learn on My Farm”—tells us why she went to horse-riding school at the age of 53, and why she kept going, even though she found it utterly terrifying.

It seemed like a simple task: Just get the pony in the pond. One step, even. Just get her hooves wet. But the pony was afraid of water—and I was afraid of the pony’s fear.

On a trail ride a few weeks earlier, this pony, Clover, had refused to cross a stream—rearing and lunging and terrifying me in the process. I’d summoned the courage to push her, only for her to take a massive, panicked jump, dumping me on the ground and galloping off. Now, my instructor and I were on a mission to desensitize her, using the pond behind the barn.

But the closer Clover and I got to the pond, the more she threatened to explode. From the ground, my instructor told me to use my leg to ease the pony forward, but I was paralyzed. The 600-pound creature was tossing her head wildly, rearing slightly. My stomach dropped every time she did this; my instinct was to soothe her, dismount, and sidle away. Don’t make it worse.

But if I let her off the hook, I’d only confirm the pony’s fears and reinforce her behavior. Plus, the real problem wasn’t her. It was me. Horses can invariably sense when you’re afraid—and fear is the one thing I hadn’t mastered when it comes to riding.

I started riding seriously two years ago. I was 53. Although I’d adored horses growing up in my Connecticut suburb, my frugal parents were uninterested in indulging my obsession. If only I’d taken up riding as a child, I used to think, perhaps I wouldn’t be so paralyzed by fear.

But the truth is, grappling with fear is one of the most rewarding things about riding. And, perhaps, about life.

Though I abandoned my dream of learning to ride as a teenager, at age 40 I moved from New York City to a farm upstate—and realized I finally had a chance to fulfill it.

The trouble is, I have never been a risk-taker. As a kid, I would only ride on roller coasters or jump off cliffs (a tiny one, once) when the social costs of not doing so outweighed my crippling fears. In riding, there are four speeds: walking, trotting, cantering, and galloping. When I began my first round of riding lessons a decade ago, I loved trotting, but I found cantering fast and scary. And jumping seemed insane.

When I eventually quit, I was relieved. My daughter, aged 12, had begun riding competitively; I no longer had the time or the money for lessons of my own. I gave up riding the way you walk away from your last swim of the summer, secretly grateful that September has arrived and you no longer have to strip down to a bathing suit and plunge into icy water.

Then, two years ago, my daughter got a summer job leading trail rides—and she kept insisting I come riding with her. So on her last day of work, in late August, we rode through the woods together for over an hour. Photos from that day show me with a huge, nearly idiotic grin. I was delighted to discover I remembered how to post at the trot—where the rider moves in the saddle, in time with the horse’s gait.

Then my daughter informed me: “We’re going to canter up that hill.”

That seemed impossible, and frightening. “What if I fall?”

“You’re not going to fall. Just hold the horn.”

So I took a deep breath and gripped the saddle horn with one hand and the horse’s mane with my other. We broke into a canter. It was disorienting; the speed at which the trees flew by was alarming. But we circled around and took a second pass, and this time I relaxed. I felt, perhaps for the first time, how thrilling it is to go thundering through the woods with such power uncoiling beneath me.

By the time we returned to the barn, my old dreams had reawakened. I wanted more of this.

That evening, I told my daughter that I’d heard you can take an equestrian holiday in Ireland. Her eyes lit up. Fired up from the ride, I booked a stay for the two of us: ten months hence, we would ride Irish sport horses over various hurdles at a cross-country estate in County Galway.

There was just one problem: I had absolutely no idea how to jump.

On a cool September afternoon in 2022, I had my first lesson at a local barn, where I soon discovered my experience wasn’t unusual. There were two other women around my age with adult or nearly adult children, both of them reviving their long-ago dream of learning to ride, just like me. Perhaps with our kids grown up, it was as simple as finally being free to return to our childhood passions. But I think it’s more than that.

I think it’s that we finally feel free to experience a little danger.

I’ve noticed that mothers of young children seem hard-wired to prioritize safety. My 28-year-old riding instructor has been in a saddle as long as she can remember, but after her son was born four years ago, she told me, “I was very nervous the first few rides, which was a brand-new feeling.” She, too, had to battle with fear. (She’s now back to training explosive horses, and going on adrenaline-fueled fox hunts.)

Another woman I met at the barn—who rode an untrained Percheron stallion as a teenager, without a helmet—lost her confidence after becoming a mother. “Up until my pregnancy there was just this limitless feeling of ‘what can I do,’ ” she remembers. “It didn’t even cross my mind that I could get hurt.”

But being a mother of two young children, she says, has “put a certain amount of fear in me that affects my confidence.” Seven years later, she’s still trying to get it back.

It turns out that combating fear is, for most people, an essential and ongoing part of learning to ride.

In most circumstances, the instinctive response to fear is to round the shoulders, protect vital organs, and keep eyes on the ground in case you fall. But with riding you are taught to do the opposite: Sit deep in the saddle, shoulders back, chest out, eyes up and ahead, even when the horse is bucking, dodging, spooking. It’s a discipline. To override your useless fear responses takes repeated practice—with fear.

Early in my lessons, I was riding a sweet, reliable mare—who really didn’t like deer. On a chilly autumn day, when I was just learning to canter, a pair of deer started crashing around in the woods that flanked the ring, and the mare started bucking. Looking back, I was hardly in danger of falling—but at the time, it was terrifying.

Another time, I was riding an elderly gelding—a retired show jumper who was now limited to trotting—when he suddenly startled and spooked, whirling around and racing across the ring. I held on for my life.

“Well, now we know he can still canter,” my instructor laughed, as I gulped air, trying to calm my racing heart.

I later told my daughter about the incident, explaining that it was scary, because I wasn’t ready for the horse to startle.

She responded: “You should always be ready.”

One day, after I fell hard off a Paint gelding who’d suddenly lunged to the left when I’d asked him to canter, I seriously questioned whether I could keep doing this. The fear felt insurmountable. But as I doggedly kept showing up to my lessons, I realized I was enjoying the feelings that accompany fear—the flood of adrenaline when you confront danger, the endorphins when you overcome it.

Besides, my ticket to Ireland was booked.

On my last day at Flowerhill Equestrian Centre in East Galway, I took a wrong turn and got trapped in a narrow dirt road, flanked by thick hedges on either side. The only way out was through—over a series of ever-larger log jumps. I hadn’t bargained for this.

With my excited horse in a full canter, I took each jump as it came—but my stomach dropped when I saw the final hurdle, wider and taller than I’d ever cleared, and coming up fast.

I panicked for a moment and tried to stop the horse, but just as quickly realized I didn’t have the time. There was nothing to do but to organize myself—heels down, chest up, look ahead—and urge him on. We sailed over the jump and cantered to the top of the lane, where we came to a stop, adrenaline coursing through my veins like cocaine.

It was one of the most thrilling moments of my life.

Back home, I continued to chase that high, and I eventually took up fox hunting. The fear may never go away, but it doesn’t paralyze me anymore.

In fact, I’ve gained so much from grappling with limited doses of fear. I don’t for a minute regret that modern life gives us few opportunities to experience real terror, but research suggests that the flood of adrenaline that comes with risky activities can leave us less anxious in normal life. I’ve even used some of my riding strategies to cope with other things that scare me.

Shoulders back. Eyes up. Look where you’re going.

A couple of weeks ago, I finally got Clover in the pond.

We’d practiced for weeks but, as usual, she lunged and dodged to get away from the water. As usual, I sat deep in the saddle—and I found the nerve to insist. I finally—finally—gave her a hard, confident bump with my heel—and she didn’t explode. She listened.

Tentatively, stopping and starting, she made her way into the pond, until the water reached her knees.

And the first thing we did when we stepped out of the water? We went back in again, over and over, until we were trotting through it.

Now, both she and I know exactly what to do when the fear settles on us.

This week on Honestly, we asked three experts to tell us: What’s school failing to teach kids? They said: basic literacy, basic math. America is falling behind in the international league tables; students haven’t recovered from Covid-related learning loss. How can we fix the crisis in American education? Click below to listen to the conversation:

Larissa Phillips lives on a farm in upstate New York. She is the founder of the Volunteer Literacy Project. Follow her on X @larissaphillip, or read her on Substack at Honey Hollow Farm.

Have you ever learned to do something terrifying? We’d love to hear about it. If you have an experience you’d like to share, write to letters@thefp.com.

To support The Free Press, subscribe today:

Real wisdom here. Thank you!

Oh thank you thank thank you for this article! At age 65 I went trail riding for the first time in 40 years last week and...LOVED IT!

And... even though we mostly walked up and down narrow, winding paths through the pinon forest and atop the high desert, with just a little bit of trotting, and I too was fearful of horses as a child, I realized: I NEED MORE OF THIS IN MY LIFE!

My kids are grown and my need to prioritize my own personal safety for their benefit instead of letting my rabid sense of adventure run free, well, it no longer has legs. So, first foray was open water swimming. Now riding (maybe I'll finally get happiness cantering and finally learn to jump!), what next? Bungie jumping? Sky-diving?? Solo-sailing around the world??? Bubbles up!!