The Free Press

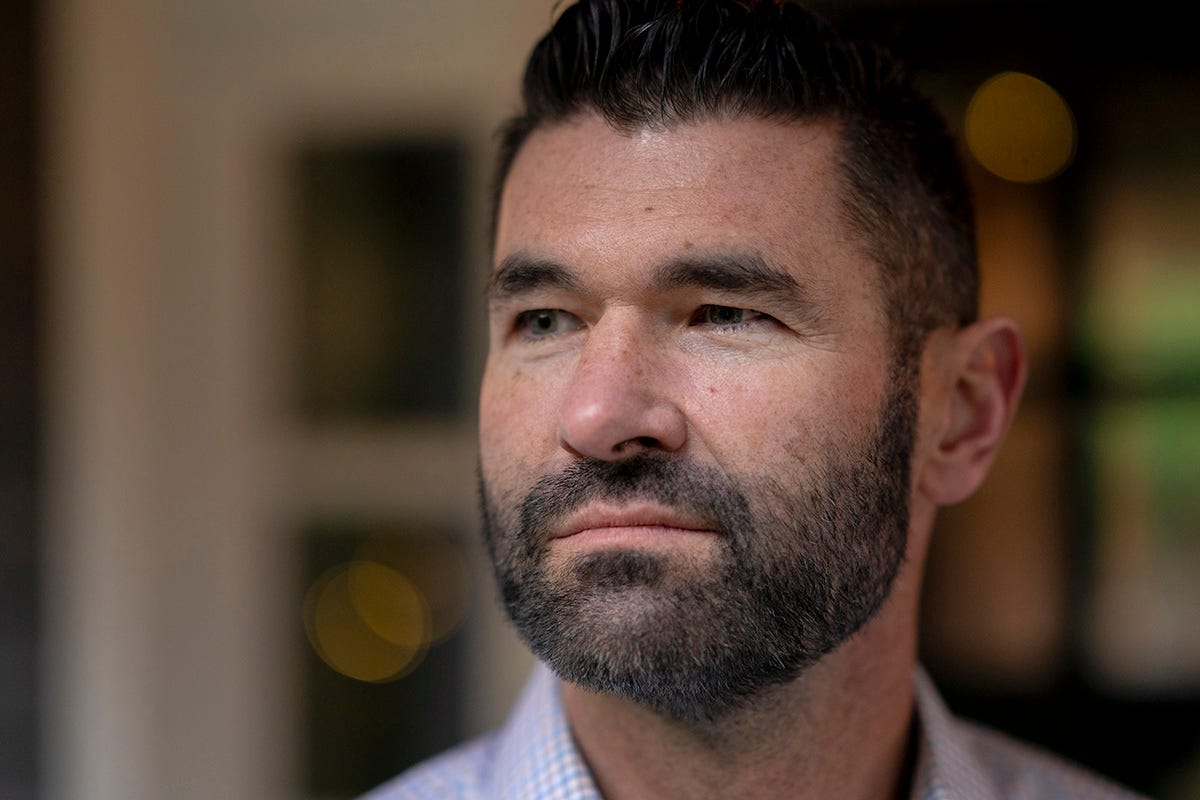

Pat McMonigle, 44, was an FBI analyst, agent, and then field supervisor over his 19-year career. During his time with the Bureau, he investigated national security crimes, served as a hostage negotiator and Joint Terrorism Task Force coordinator, trained dozens of other special agents, and was deployed three times overseas. He was awarded 24 commendations including the Combat Theater Award for his 2017 deployment to Afghanistan. But he also lost at least nine colleagues to suicide, in many cases because they suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder on the job. Then, in 2022, Pat worked on a case so devastating he was also diagnosed with PTSD. In June 2024, he finally resigned from the agency to save himself from the same fate as his fellow agents. Here, he tells his story to The Free Press.

I suppose it is fitting that my Federal Bureau of Investigation story begins—and ends—with a crisis.

I first decided that I would join the FBI after my college classmate, Deora Bodley, lost her life as a passenger on Flight 93 during the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

At the time, I was a junior at Santa Clara University. When I found out from a college memo that Deora was on that plane, I immediately changed my major from business to political science, and in 2005, I joined the FBI as an analyst. Five years later, I decided to train as a special agent at the academy. On my first day, I stood up in front of my fellow cadets and declared that I had joined the agency because I wanted to fight terrorists like the ones who stole 2,977 innocent lives, including Deora’s, that day.

More than two decades later, I made another consequential choice: to walk away from the career I had dedicated my life to, because the job had damn near broken me.

My story, sadly, is not unique.

From 2017 to 2023, I served on the FBI Agents Association Board, a group dedicated to helping the families of agents who suffered injuries or died while in service. During my time on the board, I learned the stories of at least nine FBI agents who died by suicide. Many of them had worked intense undercover roles or investigated horrific cases of crimes against children. Others suffered severe PTSD from deployments abroad, like the agent in Montana who hanged himself after surviving an improvised explosive device (IED) attack in Pakistan a few years earlier.

Almost every agent I knew was haunted by the psychological toll of the job. I remember one guy who used to keep a picture of a teenage girl in his pocket. She had been kidnapped but was never found, a victim he couldn’t save.

Like most agents, I worked tough cases and found myself in life-or-death situations. As part of the agency’s counterterrorism mission, I was deployed abroad to work with the military and CIA in war zones. Once, on Christmas Day in 2017, I was so close to an IED explosion in Kabul, Afghanistan, that I was thrown from my bed. In 2019, I was walking through the Green Zone at the U.S. embassy in Mogadishu, Somalia, when I heard air sirens ahead. I quickly took shelter in a nearby building, and the next day, I noticed that the exact spot where I had been standing was obliterated by the strike. I also did two tours in Afghanistan, including from 2017 to 2018, when I covertly assisted a U.S. military operation that killed 55 Taliban fighters.

The details of that strike are classified, so I can’t say more about it, except that it was the highlight of my career. I felt like I was making the biggest impact ridding the world of terrorists. When I was out in the field, there was so much adrenaline running through my veins. But it’s also terrifying. And when I came home to my wife and children, it could be even harder in some ways. Life is so much slower that you don’t know how to behave. There’s no threat around every corner, but you’re still looking for one. And all the while, you crave being back out in the field.

In 2019, I turned to working on domestic cases near my home in Tacoma, Washington. After my tours abroad, I didn’t expect this to be the work that would break me. But it did.

One Sunday morning, I had to tell the parents of a young man that their troubled young son had threatened a cop while high on drugs and alcohol, and the cop had shot and killed him in self-defense. I remember sitting with his mom and dad in their living room, and breaking the news as their younger children were coming down the stairs. His mother was just wailing. I tried to console the family by telling them I had lost my own child—a stillborn baby—just months before. But I didn’t know what I was doing.

Looking back, I realize I desperately needed psychological training on how to deal with these incidents, not just so that I would know what to say to the relatives of victims—but just as importantly, for myself. Although I was an FBI veteran, I didn’t know where to look for help. Occasionally, the agency sent out an email offering “helpful tips” on breathing and meditation, but this never seemed substantial given the weight of our work. It wasn’t until 2024 that I found out the Bureau even has a psychological services unit, and by then, it was too late.

In April 2022, I faced my most harrowing case, and it took place in my own neighborhood.

Bo*, a 13-year-old boy, had hanged himself on a fence behind my local grocery store. Someone had seen a video of Bo’s suicide online and shared it with his father, who reached out to the authorities for help.

I was put on the case with my partner, and the details were devastating. We discovered that Bo had been targeted by members of 764, a neo-Nazi cult that grooms kids with mental-health difficulties or gender distress. The group coerces them over the internet into mutilating their own bodies and even killing themselves. Fueled by a sick kind of social Darwinism, 764 aims to rid the world of weakness, starting with these vulnerable kids. The group had found Bo and coached him into taking his own life and streaming it on the internet.

Over the course of gathering evidence, I had to watch the awful video of Bo’s suicide at least half a dozen times. And, to gather as much evidence as possible that I hoped to use against 764, I reviewed dozens of other videos of kids harming and killing themselves.

To make matters worse, I had to fight to keep the case alive. The local U.S. Attorney’s office and even FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C., told my partner and me the investigation was a waste of time, because the suspects “had not violated federal law.” We were warned not to drain FBI resources.

Meanwhile, I couldn’t rid the image of Bo’s suicide or his innocent face from my mind.

By August 2022, with Bo’s case still unsolved, the physical and emotional toll was mounting. I started drinking too much beer at home to try and numb the pain. I struggled to sleep, and I developed a twitch in my left arm that made it hard to go about daily tasks. I was tormented by nightmares—not just about Bo—but about my own wife and four kids. I would wake up in the middle of the night in sweats, fearing that they were in danger or had died. For a period, I didn’t trust myself to carry my gun—fearful I might use it to hurt myself. I locked it up in a safe at home and asked my wife to hold the key.

Even though I tried to put on a brave face and go to work, eventually that suffered, too. I stopped going on arrests or surveillance. I was a completely ineffective negotiator. My nerves were shot.

Finally, by September, my wife—who is a therapist—forced me to see a psychiatric nurse who diagnosed me with PTSD. I told the nurse that wasn’t possible because PTSD was for “tough guys like Green Berets.” At the time, I was oblivious to the idea that my symptoms could have anything to do with my work.

When I told my direct supervisor about my diagnosis, she listened and expressed sympathy. But that’s all she could do. There is no formal process at the Bureau to handle cases like mine.

For another year, I cycled through antidepressants and tried weekly eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy—which I had to pay for myself. I found a great counselor, a former detective, who also helped because she understood my work. But treatment can only do so much. I kept asking myself: What is wrong with you? My dad was a decorated war hero with two tours in Vietnam. The horrors he must have witnessed! My partner was a former Marine with combat deployments. He worked the case even harder than I did. Why was I the one falling apart?

Then one sunny and clear September afternoon in 2023, when I thought I was feeling pretty good, I took my son to football practice. As I sat on the bleachers and watched him run through sprints and throw balls, I opened my phone and saw an email from Bo’s mom. It was around the time of his birthday, and the message included pictures of him, smiling, as well as a note of gratitude for me and my partner. She told us she felt like nobody else in the world cared about finding justice for her son but us. But, in my troubled mind, this only made me feel worse. I hadn’t brought Bo’s killers to justice. I felt like I had let his family down.

Suddenly, I broke down crying, right in front of all the kids, coaches, parents, and bystanders. I’m sure the kids on the field stopped and stared, but I honestly can’t remember. Finally, a friend took me home. When I arrived on my doorstep, my wife hugged me and put me straight to bed.

The next day I called The Chateau, a residential treatment center in Utah for first responders with PTSD. The person who answered the phone was named “Shepherd,” and he certainly was one—a retired highway patrol captain who had once “been there” himself. Within two weeks, I was on a plane to Utah.

I spent 30 days in the Wasatch Mountains alongside 15 others. Cops, firefighters, and paramedics—the lucky “survivors” of trauma on the job. Each day we did yoga and therapy. We went on hikes and listened to lectures on confidence and mental health.

My old self started to return. But once my month there was up, I had to go straight back to work, and I was put on the case of a preschool aide who we suspected was a member of the same 764 cult that had targeted Bo. My demons surfaced again. Finally, I asked to be reassigned to an administrative job—not exactly why I joined the FBI.

In February 2024, when it came time for my yearly medical checkup, I told the doctor about my PTSD diagnosis and the antidepressant I was taking. That’s when I first heard of the FBI’s psychological services unit—because a couple weeks later, rather than offer me help, they put me under investigation.

First, the unit sent emails to several of my colleagues, disclosing my PTSD, and interviewed them about my condition. I was told that my clearance would be pulled unless I consented to this. Then, the FBI psychologist ordered me to give up my gun to a firearm instructor who happened to be a friend of mine. Usually, turning in your gun is a sign you’ve done something wrong, and I felt deeply ashamed, like a person who had stolen cocaine from the evidence locker.

The message from the FBI was clear: I was no longer an agent to them. I was a liability.

Of course, I understand why the agency would want to protect itself. But the best way to do that is to be proactive, and help prevent agents from sinking into despair. The FBI should learn from other large police departments and the military and provide agents with yearly check-ins with counselors, who can build a long-term relationship with these first responders. When they come home from deployments, the agency should require its staffers to go through a reintegration program to help them transition back to life at home. And when agents take initiative to seek out the care they need, they should not be punished for it like I was.

[When The Free Press asked the FBI for comment on this story, an agency spokesperson said it employs “licensed clinicians and trained peer counselors” to “support their fellow FBI employees facing a variety of challenges, including stress, marital, parenting, and elder care issues, financial issues, alcohol and/or drug abuse, work-life balance, depression and anxiety, grief, and suicide.” These services are available “to all employees and their eligible family members, including free and confidential counseling and referrals to external resources.”]

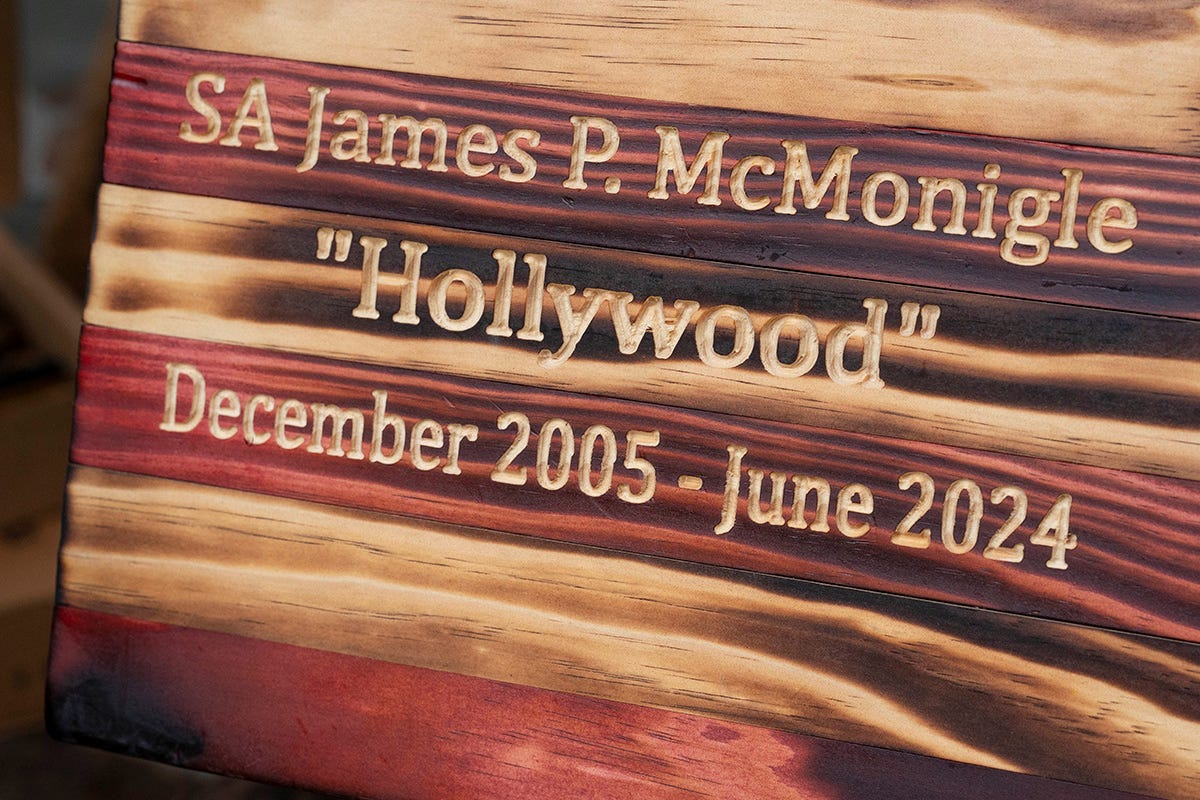

Whatever services the FBI offers its employees, I wasn’t aware of them despite having served on the board of the FBI Agents Association for six years. In June 2024, at age 44, I finally decided to hand in my notice. I emailed my resignation letter to my supervisor, and said, “My medical team has advised me to leave the work and the organization as a whole.” I added that the Bureau “shows little regard for its own agents. I’ve experienced it now personally.”

My supervisor was understanding, but I never got a response from anyone higher up in the agency. The next day when I went to the office to pack up my things, I couldn’t get into the building. My pass had been deactivated.

Six months later, I’m working as a security consultant, and writing a couple of screenplays inspired by my time in the FBI, while also enjoying more time with my wife and our four wonderful children. I miss my agency pals, and our camaraderie in the bullpen. But, most of all, I miss the mission and the excitement. Looking back, I realize I was just a normal guy who had a normal reaction to terror. There wasn’t anything wrong with me. I simply needed help.

This week, the FBI is poised to move into a new era under Kash Patel, Trump’s nominee to lead the agency. I’ll be rooting for him when he faces his Senate hearing tomorrow. He’s expected to take a wrecking ball to the organization, and I have sympathy for that. The FBI is desperately in need of change.

If I could speak to Patel, I’d tell him: Respect your people. Pay them enough to provide for their families. Increase the number of special agents—which has remained at 13,700 for as long as I can remember, despite the Global War on Terror, despite the spike in online predation, despite the immense counterintelligence threat posed by Russia and China. And make mental health a priority. Every single agent should be given the tools to do their jobs without having to pay the ultimate price.

Even now, I keep hearing about FBI agents who’ve snapped or taken their lives. A few months ago, I learned that a retired FBI agent in a mental health crisis was shot and killed by a school district officer after he was caught throwing rocks at a public school in El Paso, Texas. Last fall, I was told that an agent—haunted by memories of identifying victims from the remains of the 2023 Maui fires—had killed himself.

How many more agents do we have to lose before the government wakes up? Kash Patel, I’m begging you: Be the first FBI director to take a stand.

* Bo’s name has been changed to protect his identity

—As told to Frannie Block