The Free Press

There are some years people would like wiped from history—and who can blame them? Who can blame the newly sober for pretending now that the excesses of progressive reign from 2018 to 2024 never happened? Who can blame them for thinking those who were canceled, even wrongly canceled, still probably deserved it a little bit? It’s important to just move on and forget, to stop nitpicking. It was mostly right. Because if an entire wealthy, elite college town became convinced, let’s say, that white middle schoolers hung nooses to intimidate black teachers and students, if those children were smeared by the leaders of the school and the community, if protests were organized, and if a family had to leave town, there must have been at least a kernel of truth. It’s too destabilizing if it was entirely a lie. It’s too threatening.

In the proper telling of those years of progressive rage, there were no real victims at all. But of course there were victims. Here for the first time, parents of a boy from Evanston, Illinois, who were caught in a national maelstrom speak to Frannie Block about what happened when a conspiracy against their son became too big to fail. —Nellie Bowles

“Every Friday the 13th, I’m reminded of it.”

Mike Klotz is not a superstitious man. But he acknowledges that the event that turned his life upside down happened on the unluckiest day of the year.

It was May 2022, a cool and overcast spring morning in Evanston, Illinois. Klotz can’t recall his 12-year-old son leaving the house—it was just a normal day—but he said the sixth grader would have walked, as usual, to Haven Middle School, accompanied by his 13-year-old brother.

According to staff members who were in the building that day, the atmosphere at Haven was tense—a group of students was staging a protest about the transfer of a few popular teachers.

But things were often tense at Haven, a school notorious for its violence, and where nearly 30 percent of students are considered low income. One teacher who worked there at the time—but has since left—told me that he “didn’t feel safe in the building.” He constantly feared “verbal and physical assault,” and “knew if something had happened to me, I wouldn’t be protected by the district.”

“We wouldn’t walk the hallways in between class periods because it was unsafe,” he told me. “That’s how bad it was.”

Klotz himself had spent two and a half years working as a special education teacher at Haven, but he said he resigned in early January 2022 because he no longer felt safe as a teacher there. But his own kids had to keep attending this school, he said, “because we really didn’t have much of a choice.” It’s not like they could have afforded private school, if they’d even wanted to send their kids somewhere else. “We are a household of public servants and moved to Evanston for the schools,” he told me.

Then came that Friday the 13th. By lunchtime, what had begun as a peaceful protest devolved into what one teacher described to me as “an absolute mob scene.” Inside the school, seventh and eighth graders were running through the hallways, slamming locker doors shut, and chanting “Fuck Latting,” referring to Haven’s principal, Christopher Latting. Someone called the police.

Klotz’s son wasn’t involved in any of this. He was outside, in the schoolyard, with the rest of the sixth grade.

But what happened in the schoolyard over the next several minutes would disrupt his family, subject them to a witch hunt, and ultimately force them to move out of town, Klotz told me.

Here’s how he tells the story:

First, a sixth grader—an 11-year-old friend of Klotz’s son—pulled three jump ropes out of a recess bin and started tying them in knots.

He started fashioning them into nooses. He made three. Another child saw that he seemed upset, so he ran up to Klotz’s son and asked him to come speak to his friend. Klotz’s son crossed the yard to ask the boy what he was doing—and checked if he was okay.

The two friends spoke a little. Then the child who made the nooses hung them on a small, shrub-like tree, and the two boys ran off to another part of the yard, leaving the ropes hanging a few feet off the ground. It wasn’t long until a parent caught sight of them—and immediately alerted the police.

Three hours later, at 5:08 p.m., every family with a child in Evanston/Skokie School District 65—which contains 18 schools—got an email from then-superintendent Devon Horton, a well-known pioneer of “antiracist” education. The subject line read: “Haven Student Sit-in & Hate Crime.”

In the email, Horton stated that parents had “reported finding three nooses hanging from trees” on the grounds of Haven, and wrote:

“This is a hate crime and a deliberate and specific incidence of an outwardly racist act. It resounds with a tone of hate and hurt that will impact members of our entire community, namely Black and African American students, staff, and families who have experienced generations of harm.”

Horton also wrote that “institutionalized racism has been used in the past to intimidate and discourage minority leaders.” Horton didn’t reference specific minority leaders, but both he and Principal Latting are black. Both men declined to respond to multiple requests for comment on this story. In an email to The Free Press, Latting wrote: “That time was profoundly traumatic for me, the students, staff, and the entire Haven community. As such, I am not in a place to revisit or discuss those experiences, even informally.”

A representative from District 65 told The Free Press via email that “Our belief is that the initial statement was intended to explicitly name the deeply rooted harm of overt, racist symbolism and to ensure that it was crystal clear that hate, in any form, will not be tolerated in our school district.”

When Klotz read the email that Friday evening, his 12-year-old son was on his way to scout camp for the night. He had no idea his boy had witnessed the alleged hate crime, but he remembers thinking the email had jumped to conclusions in a way that seemed “reckless.” In Illinois, a hate crime is a felony, with a minimum of one year in prison.

His wife, Melissa Klotz, told me her first thought when she read the email was: “What actually happened? Because, when anything happened at that school or in that district, you would always only get a partial story that may not be true.”

The next morning Mike Klotz got a call. It was the father of his son’s friend—the one who’d tied the nooses, and he said: My son was involved, and so was yours. (The Free Press is withholding the names of both boys to protect their privacy. The family of the other boy declined to participate in this story.)

After his son got home from camp that Sunday, Klotz asked him what had happened. The 12-year-old said he had asked if his friend was okay, and watched him hang the ropes in a tree. “I did not take his word for it,” Klotz told me. “I asked around. Two or three other people”—teachers, parents—“told me the exact same story.”

The Klotzes had been ready to accept that their son had done something wrong. But after learning the full story from others on Sunday, he felt the opposite. “I was damn proud of him,” Klotz told me. “He went and checked in on his friend. That’s all he’s guilty of. We should all be so lucky to have a friend like that.”

Even so, over the weekend, Klotz also started seeing other Haven parents on Facebook speculating about the “hate crime”—and the identities of the children who’d committed it. Although Klotz didn’t see his child’s name mentioned, he was worried enough to keep both of his sons home from school on Monday.

That evening, Haven parents got another email, this time from Principal Latting, who wrote that in response to “the hate crime,” the school would be bringing in “equity consultants” to “help the Haven community process and share their truth about the events that occurred on Friday,” and to enable “productive and necessary conversations around racial equity.”

One educator told me that the following week in class, teachers were instructed to give children time to discuss their feelings. During one session, the teacher said she asked her sixth-grade class if they knew what nooses symbolize. “Only two of the students had any knowledge of the fact that nooses had any kind of racialized meaning,” she said. “Every single other student thought that a noose symbolized and represented suicide.”

Klotz told me it’s not until eighth grade that Haven teaches kids about nooses being a symbol of America’s racist past. “And how do I know that, you’re wondering?” he asked me. “I taught the class.”

On Thursday night, Klotz received another email from the principal. This one was addressed only to him. Latting informed Klotz that his 12-year-old was being placed on “administrative absence”—effective immediately—because he had been “present during the incident which occurred last Friday, May 13.”

I asked the Klotzes if they were concerned, at that moment, that their son may have been complicit in a hate crime.

“I know my son,” said Melissa. “I know that he is not a perfect angel, and every kid can make mistakes. But I also know how he’s grown up, and the friends he’s had over time, and the neighborhood that we lived in—and my kid doesn’t have a racist bone in his body. There’s no way that could have been what happened.”

Mike Klotz said his initial reaction to the email was “anger”—which came from “a place of helplessness, that we couldn’t seem to improve the situation at all.” He was speaking regularly to the family of the boy who’d tied the ropes, and learned that he had also been put on administrative absence from school. All the two families could do was wait for police to complete their investigation.

It took six weeks. In the meantime, both kids missed the rest of sixth grade.

During this time, the Klotz family said they were terrified that their son’s involvement in the case would become public knowledge. Melissa described how she felt at the time about the actions the school could take: “They’re going to send our name to the entire community and try to present that narrative that we are these awful racist people.”

At the time, she was a town planner with over a decade of experience working for the local authority in Evanston, but her career suddenly felt fragile. “Am I going to lose my job? Am I going to get attacked? Are my kids going to get attacked?” she wondered. “It made us feel so unsafe.”

This article is the first time the Klotzes have been publicly identified as the parents of one of the two children involved in the incident. Speaking exclusively to The Free Press, the couple said they thought long and hard about whether they wanted to waive their anonymity. They said they are doing so because they believe the school falsely presented their son as racist—and never corrected that narrative when evidence showed it wasn’t true. Even after police concluded that no hate crime occurred, they said the school never apologized.

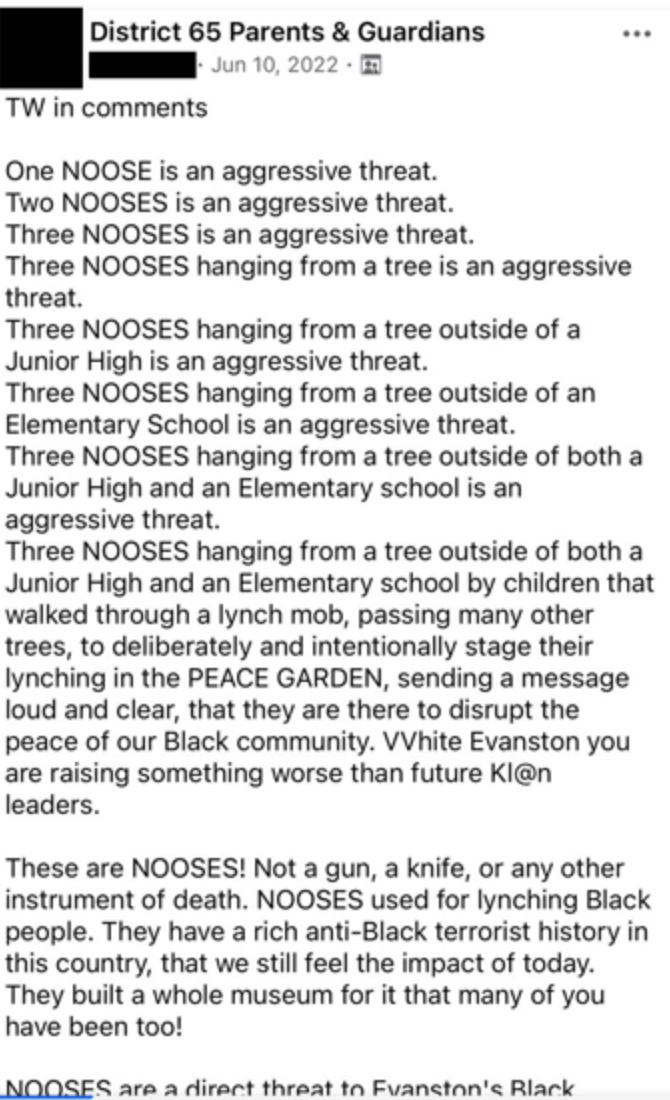

While a misunderstanding over a noose at a middle school back in 2022 may seem like a small matter, the incident mushroomed into something much larger: a symbol of the ideologically fueled hysteria that swept America in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, with adults publicly condemning two children, on social media and in school board meetings, of being “future Klan leaders” with “murderous values,” who were guilty of “an act of racial terrorizing.”

Mike Klotz told me the town’s reaction to the event was so extreme, “We had to fucking move because of it.”

The police completed their investigation on June 22, after the school year had finished, according to a police statement that same day. The “nooses,” police concluded in their report, weren’t a symbol of racial hatred, but were likely “a cry for help.”

The final, 33-page police report detailing the authorities’ investigation —which Klotz showed to The Free Press after it was made available via a Freedom of Information Act request—states that the boy responsible for putting the ropes in the trees “has some very serious mental health issues and has tied knots previously as a soothing technique.”

According to the report, police spoke to a Haven student who said she watched a boy “place the rope over a tree, and put the noose around his neck for approximately 1 to 2 minutes.” She said the boy had a “look on his face” that was “serious,” and he “appeared as though he did not want to be there.” She told police other students there were worried he might “harm himself,” but added: “The tree the rope was placed over was not big enough to hold his weight.”

Two days after the incident, the father of the 11-year-old accused hate criminal told a Haven staffer that “his son was in the midst of a mental health crisis when this incident occurred,” according to the report.

Three hours after the Evanston Police Department issued its public statement on June 22, Superintendent Horton sent an email to every parent in the district acknowledging that law enforcement did not consider the noose incident a hate crime. And yet, he wrote, the school district would continue to investigate and, if necessary, punish the students involved.

“The actions and motive of the involved juvenile did not meet the legal, statutory elements of a hate crime,” Horton admitted in the email. But, he wrote, “The district will move forward with its own internal investigation to determine the appropriate level of interventions, both disciplinary and restorative.”

He added: “We fully recognize the harm of these actions on our community, especially for our Black students, staff, families, and residents.”

Horton wasn’t the only person in Evanston who seemed to reject the police’s findings.

A member of the “District 65 Parents & Guardians” Facebook group demanded that the family involved “be outed so the citizens of this town know who the terrorists are.”

Another insisted that community members “call them out on their white privilege and racist behavior.” Someone said the parents of the young suspect ought to be sued.

When I reached Commander Ryan Glew, the public information officer of the Evanston Police Department, over the phone, he reiterated the findings of the report. And when I asked why the incident is still widely assumed to be a hate crime, he said: “People are going to act off the information they’ve been given.” But it’s the job of the police department, he added, to ask: “What are the facts? What’s the entire incident?”

Even after police concluded no hate crime had been committed, the office of Cook County prosecutor Kim Foxx went on to punish the troubled sixth grader who tied the knots in the schoolyard, charging him with disorderly conduct. In Illinois, Glew said, “disorderly conduct” is defined as “acting in a way that disturbs others.” In the case of the incident at Haven, he explained, “individuals that had witnessed this, or were aware of it, felt alarmed and threatened.”

Glew told me the child who tied the nooses was referred to juvenile court, which ultimately concluded the incident would not be “treated as a criminal matter.”

Meanwhile, the Klotzes realized that in Evanston, the narrative was set in stone. Mike Klotz said an apology is “the only thing I really even want.” But one teacher, who has worked in the district for 15 years, told me that in order for that to happen, “Somebody would have to acknowledge they were wrong.”

A spokesperson from the district did not answer a question about whether the students should be given an apology for what happened, although she acknowledged that “This incident caused significant and longstanding harm to the individuals directly and indirectly involved, to the overall school community, and to residents across Evanston/Skokie.”

“Since this incident,” the spokesperson added, “our district has reflected on our crisis response efforts in various situations to enhance and improve upon them. This includes increased and proactive coordination and communication with our local first responders, including the Evanston Police Department.”

Evanston lies on the shore of Lake Michigan, about 12 miles north of downtown Chicago. Home to Northwestern University, the leafy college town is known for its cute coffee shops and well-kept homes, occupied by professors and professionals. With an average house price of $475,000, even “median-income” families are priced out of living here.

But Evanston is cut in half by a railroad track that runs along the lake’s western edge—from Chicago to Milwaukee and beyond. And on the west side of the track, you can find reminders of the city’s uncomfortable history. Haven Middle School sits right in the middle of this divide, an institution for both the city’s wealthy and poor.

For much of the 20th century, until the 1960s, most realtors in Evanston practiced “racial zoning,” refusing to rent or sell homes in the more prosperous parts of the city to non-white buyers. The black community was effectively confined to the insalubrious 5th Ward—an industrial district that is home to the city dump.

Despite—or perhaps because of—Evanston’s racist past, the city has swung to the opposite extreme in the last decade or so, implementing some of the most progressive racial policies in the nation. In 2021, for example, the city became the first in the country to pass a reparations law, offering housing grants to black families to make up for the discriminatory practices of the past. Locals argue that the law doesn’t go far enough, and that the money should instead “go directly in the hands of” black residents.

“We got a bunch of violence going on at this school, and now all of a sudden this happened, and nobody talked anything about any of those things ever again. It was hate crime, hate crime, hate crime, hate crime.” —Mike Klotz

But these attempts to right historic wrongs have done little to redress problems that ordinary Evanstonians face, one teacher at Haven Middle School told me. “Everybody’s so focused on race,” she said, “instead of figuring out how to work with people to improve what’s going on.”

According to Klotz, after Superintendent Horton sent out the first email about the hate crime, parents immediately forgot that the school had been the scene of a riot earlier that day, as students protested the transfer of teachers, leading to chaos in the halls and students leaving the building without permission. “We got a bunch of violence going on at this school, and now all of a sudden this happened, and nobody talked anything about any of those things ever again,” he said. “It was hate crime, hate crime, hate crime, hate crime.”

One former Haven teacher who has worked in the district for over a decade agreed with that. “It is a better story,” she said, “the idea that the community still has so much growing to do, and there’s still so much racism.”

Indeed, a few days after the “hate crime” incident, the Chicago-based advocacy group Ex-Cons for Community and Social Change invited locals to gather outside the school “to show children they are not alone.” A flyer for the protest was posted to the “District 65 Parents & Guardians” Facebook group.

About a dozen protesters showed up at Haven on May 23, 10 days after the incident, and stood directly outside the entrance as students walked into the building to start the school day, chanting into a megaphone. “We stand here today to say we want an immediate investigation, and we want to know the transparency of that investigation,” said Tyrone Muhammad, the group’s executive director. After a couple of days of this, Principal Latting sent an email to all parents at Haven, telling them the school would “support the rights” of the group who were “peacefully protesting following the hateful and racist hanging of three nooses on school property on May 13.”

On May 23, 2022, while police were still conducting their investigation, the Evanston school board held a regular public meeting where community members and activists piled in to demand “accountability.” The entire four-hour-long meeting was recorded.

In the video, it’s hard to see how large the audience is, but a steady stream of people flowed into the room for about half an hour—including at least eight members of Ex-Cons for Community and Social Change—wearing matching all-black pants, boots, and crewneck sweatshirts.

Almost everyone visible in the video—the entire board and members of the community—is wearing masks, occasionally taking them off to speak. After a land acknowledgment and a few agenda items, the conversation soon turns to the supposed hate crime.

Horton is the first to speak. He says, “I sit here with armed security 24 hours a day because of our efforts to fight—” he then pauses, looking down at his notes, before continuing with a slight quiver in his voice: “That’s not healthy for anyone.” He then calls the reactions to the noose incident, and to his work on “equity,” as “outright racist,” as the crowd erupts in applause and collective cheers.

Five board members then give talks, each one drawing the same conclusion. One board member, Soo La Kim—who is also the assistant dean of graduate programs at Northwestern’s School of Professional Studies—says the students involved in the noose incident “translated the subtext of anti-black adult discourse into the text of profanity-laced chants and an act of racial terrorizing.”

“By the way,” Kim continues, “the suggestion circulating that perhaps these were not in fact nooses representing lynching but lassos or something else is offensive on multiple levels. That kind of denial—in the face of facts, context, and history—is gaslighting of the worst kind.”

Another member, Elisabeth Lindsay-Ryan, who also works as a professional diversity, equity, and inclusion consultant, says: “I’m hoping that since our children have chosen to use nooses—a symbol of white terrorism, white supremacy, and murder—in their advocacy, that at least some of you will finally listen and reflect on the ways you are participating in this pattern.”

Afterward, board member Anya Tanyavutti chimes in, saying the district’s students are being taught “murderous values.”

Board member Marquise Weatherspoon then says she always intended to use her school board seat “to speak on what is the obvious.”

“And the obvious is . . . this community is racist; it’s harmful; and it is hurtful to all of us. And our children are not safe here.”

None of the board members cited in this piece returned emails from The Free Press seeking comment.

As the school board meeting raged, Klotz stayed at home. That same year, he had planned to run for a seat on the board, but after he saw the district’s response to the nooses, he concluded, “It’s too fucked up here. One person cannot make a difference.”

Even now, he said he can’t bring himself to watch the recording of the meeting, especially as he saw how the outrage spread into the community. On June 10, Klotz saw a post in the District 65 Parents & Guardians Facebook group: “VVhite Evanston you are raising something worse than future Kl@n leaders.”

After the police report came out on June 22, 2022, another wrote: “We know who you are. No, really we know who you are. . . . You’re a bigot that’s raising terrorists, terrorists that are skilled at tying nooses for stealing the lives of Black people in a long gruesome, hands on murder.”

The Klotzes were terrified the community would come after them. “In a socially progressive town such as Evanston, to be accused of something like that is like a death sentence, a social death sentence,” said Mike.

Though the Klotzes have never been publicly connected to the “hate crime,” local parents noticed that their son had stopped attending school. Melissa told me that people at work figured out her son had been involved in the incident. “It ruined my reputation in the city,” she said. “I had relationships in the city that just completely went down the drain because of it.”

Melissa told me she sees herself as an “extremely liberal person” who wants to live where she works, and “be a part of the community, and be useful and helpful to that community.” She told me she and her husband had dreamed of moving to Evanston because it “is a beautiful place and a very diverse place, and it literally just checks all of those boxes.”

But after experiencing so much online rancor, they put their dream home up for sale in the summer of 2022.

Months later, the Klotz family moved to Lincolnwood, Illinois, about six miles down the road from Evanston. It was close enough that Melissa could still commute to her job in the town, but far enough that their kids could go to a new school district.

Just before Thanksgiving, I visited the Klotzes at their Lincolnwood home, where they’ve now lived for two and a half years. Approaching the front door, I was greeted by a Ruth Bader Ginsburg bobblehead proudly displayed on the stoop. Klotz—tall and bald with a long, shaggy beard and sleeves of colorful tattoos—told me he has always considered himself a “hardcore liberal.” But even he believes that progressive politics in his old town “have gone completely cuckoo.”

“I’ve lost faith in everything. Now I just assume all people are bad people, unless they can prove otherwise.” —Melissa Klotz

Last fall, Melissa quit her job as an Evanston town planner, but she said she still experiences severe paranoia every time she goes back to Evanston for work as a consultant. Whenever she interacts with people in the city, she asks herself: Do I tell this whole story to this person, and are they going to believe me? Or are they going to think I’m a horrible, racist person?

Melissa told me that what happened to her son completely changed her perspective on life. She said she’s now cynical about politics, and she’ll never vote again.

“I’ve lost faith in everything,” she said. “Now I just assume all people are bad people, unless they can prove otherwise.”

False alarms over hate crimes seem to have become increasingly common in American life. There was the time, in August 2017, when a group of black sorority sisters at the University of Mississippi discovered a banana peel in a tree and saw it as racist “symbolism,” which led to the cancellation of a campus event—even though it later transpired the peel had been discarded by a student who said he couldn’t find a trash can.

Then, last summer, in a case that has eerie parallels to the controversy in Evanston, a mentally unwell teen at a Missouri high school hung a noose in a school bathroom, which the community immediately assumed was a hate crime. But school officials later said the kid who hung the noose “was in a crisis” and that the crime was not “a racially motivated incident.”

The College Fix, an online outlet for university students, has documented other instances at schools where objects first thought to be nooses turned out to be completely innocent: a lost shoelace hanging inside a dorm at Michigan State in October 2017; a lasso that was a part of a Wake Forest student’s cowboy costume in February 2019; a fishing knot outside the University of Michigan hospital in July 2019.

But the most famous hate-crime-that-wasn’t happened in January 2019, when black actor Jussie Smollett claimed two men attacked him in Chicago, wrapping a noose around his neck while yelling: “This is MAGA country.” Kim Foxx—the prosecutor whose office charged the Haven sixth grader with disorderly conduct for tying “nooses”—charged Smollett with 16 counts of disorderly conduct for lying to the police. But a few weeks later, she dropped all the charges, citing Smollett’s “agreement to forfeit his bond to the City of Chicago.” Smollett was later convicted of lying to the police, who said he paid two men $3,500 to assault him, though the conviction was later overturned on appeal.

Professor Wilfred Reilly, a political scientist based at Kentucky State University, has researched these incidents in depth, resulting in the 2019 book Hate Crime Hoax: How the Left Is Selling a Fake Race War. A self-confessed “proud black man” who views his work as “pro-American and profoundly pro-black,” Reilly told me the idea that racist signs are ever present undermines genuine claims of racism.

“There’s an incentive structure that encourages you to say, ‘Yes, my school is run by racists, and my students are Nazis.’ That’s clearly very unhealthy, but that is the structure. Like, you want to be the principal that’s in there fighting racism.” —Wilfred Reilly, author of Hate Crime Hoax

“In contemporary upper-middle-class life, where a third of the country falls, we’ve attached a value to victimization,” he said. This means society “gives a lot of power to people” who identify as victims.

And so, he argued, there are people in positions of authority—particularly at schools—who benefit from hate crime hoaxes. “There’s an incentive structure that encourages you to say, ‘Yes, my school is run by racists, and my students are Nazis,’ ” Reilly said. “That’s clearly very unhealthy, but that is the structure. Like, you want to be the principal that’s in there fighting racism.”

In the summer of 2020, in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, these ideologies were at the pinnacle of their power. The movement’s thought leaders like Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi, a 2021 recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant, “were practically treated like saints,” according to Coleman Hughes, author of The End of Race Politics: Arguments for a Colorblind America. Major Fortune 500 companies started hiring directors of diversity, equity, and inclusion and shelling out thousands of dollars for seminars with experts like DiAngelo, whose book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism had become a mainstay on The New York Times’ bestseller list.

Devon Horton began his tenure as superintendent of District 65 in July 2020, soon after Floyd was murdered by police in Minneapolis. A Chicago native who had been working as a chief of schools in Louisville, Kentucky, Horton had been hired to implement his ideas about diversity, equity, and inclusion, with the district endorsing his previous achievement of “a district-wide racial equity policy.”

His ideas—about fighting racism through active “antiracism”—quickly attracted national attention. In October 2020, he was featured in a glossy profile in The Wall Street Journal titled, “Can School be ‘Antiracist’? A New Superintendent in Evanston, Ill., Has a Plan.” The piece laid out Horton’s philosophy: That all aspects of schooling should be infused with antiracism—such as giving “students from marginalized groups first priority” for in-person learning, and encouraging teachers to no longer base grades on whether students completed their homework. In the interview, he said his district wouldn’t hire any teachers who didn’t agree. “If you’re not antiracist,” Horton said, “we can’t have you in front of our students.”

In January 2021, a few months after the profile was published, Horton claimed in a public meeting that board members and administrators had received death threats because of the district’s antiracism policies. This prompted the district to supply him with a personal security team for seven months, at a reported cost of $50,000 a month to local taxpayers.

But whatever threats had come in, none were ever brought to local enforcement. The Evanston Police Department told me the department “did not have any reports of death threats” against Horton and that “no overt threats against employees” of the school district had been reported.

In the summer of 2023, one year after the “hate crime” incident, Horton left Haven to run the DeKalb County School District in the Atlanta suburbs. During his three-year tenure as school superintendent of Evanston, he had implemented some equity initiatives, maintaining lucrative contracts with equity consultants like the Pacific Educational Group, and introducing “restorative justice” practices in schools that prioritize “community” and view discipline as a “last resort.”

But it’s unclear what, if any, impact these programs had on educational outcomes for students of color.

Last November, a district-wide “Equity Progress Indicator” report showed that the racial achievement gap in Evanston has actually been widening. The percentage of black students meeting standards in language arts dropped from 33.4 in the 2023-24 school year to 31.7 the following year, whereas that same metric for white students stayed consistent, at around 82 percent. In the meantime, enrollment in District 65 has continued to fall.

But Horton did enjoy one notable achievement: In November 2022, just six months after the Haven “hate crime” incident, the National Alliance of Black School Educators named him “Superintendent of the Year.”

To Mike Klotz, Devon Horton is “a comic book-level villain” who used a story about a hate crime to distract the people of Evanston from his own incompetence.

And yet, he is sympathetic to his former neighbors. Like most of them, Klotz believes it’s necessary to right the wrongs of America’s racist past and fight for a fairer society. He still describes himself as a progressive.

“I know a lot of very kind people in Evanston that want to do the right thing,” said Klotz, who now works as a teacher at a new school district. “The problem is that they’ve gotten wrapped up in a cult-like belief.” He added that the trouble with the ideology of antiracism, as it was practiced in Evanston, is this: “You can’t disagree. Disagreement means disharmony. Everyone is either an evil-doer or a good-doer and there’s nobody in between.”

Klotz’s son is now in his freshman year at the local high school in Lincolnwood. But he’s still grappling with the aftermath of what happened that Friday the 13th.

“He had straight A’s in Evanston,” Melissa told me. “He’s very smart.” But now, “He is struggling to get through school. I don’t know if he’ll graduate high school.”

She added that the family has spent around $10,000 on private tutoring to help him focus on his studies, but she’s worried the problem runs too deep. “He’s never going to trust adults in education. And I don’t blame him one bit,” said Melissa. “He cannot go into a public school building and have any trust in any adult. It ruined his educational career.”

What continues to nag at Mike is “there’s no one that’s paid any consequences for this whatsoever.”

A teacher who worked at Haven agrees with that. “The truth of the matter is there was a kid crying out for help, and our responsibility—as a school, as a school district, as a staff—was to understand that and to respond to that,” she said. Instead, “those children were ignored, dismissed, neglected so severely, which I think is unconscionable.”

Sitting on the couch in his Lincolnwood living room, Mike throws his hands up as he describes his need for justice.

“I’ll be honest with you, I want my pound of flesh,” he said. “Without the truth getting out there, we can’t move on.”

But “the story was too good,” Mike concludes with a shrug, while his old dog with a pink mohawk snores at his feet.

“The truth didn’t matter.”

Join Frannie Block next week for a livestream with Mike Klotz about his story, only for paid subscribers of The Free Press. Come to our website on Tuesday, April 1, at 5 p.m. ET to watch the conversation.