The Free Press

Should I take the deferred resignation deal? Is it a scam? If I don’t take the deal, will I be fired without the purported benefits of the deal? Will my agency even exist one, two, or six months from now?

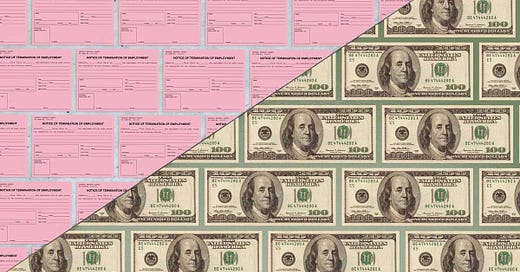

When corporations announce company-wide buyouts, it invariably causes confusion, stress, and anxiety. But what about when it’s the federal workforce, where buyouts are unheard of? And the actual mechanics of the buyout are far from clear? And I have only a week to decide? (The deadline is February 6.) These are the kinds of questions federal workers are asking one another ahead of the deadline to accept the “deferred resignation” deal offered in an email sent to everyone in the federal government last week.

The email was titled “Fork in the Road”—the same headline of the email Elon Musk sent to employees of Twitter (now known as X), the company he bought in 2022, and which now operates with 20 percent of the staff it had when he acquired it. It offered everyone in the federal bureaucracy something it called a “deferred resignation”; employees would get their full pay and benefits through September 2025, but would no longer be required to work. Along with the carrot came the stick: For those who didn’t take the deal, the email added, their jobs weren’t guaranteed.

In recent days, The Free Press has heard from some two dozen federal employees about the buyout plan. By corporate standards, its provisions are pretty generous, amounting to close to eight months of severance pay.

Indeed, on X, Musk’s new Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) made it sound pretty enticing. “[You] can take the vacation you always wanted, or just watch movies and chill, while receiving your full government pay and benefits.”

But neither carrot nor stick are causing federal workers to jump at the offer. Some worry about whether the program is legal; others fear that payments will be cut off if there’s a government shutdown. “The biggest thing people are wondering is if it’s legitimate,” said one USAID employee. “There’s a lot of fear that if people take the deal, the rug can be pulled out from underneath them.” (All the employees who spoke to The Free Press requested anonymity, for fear of being fired.)

What’s more, many federal employees find the offer offensive. “It has almost encouraged some people to dig in their heels and fight it out because they believe in their jobs, they’re dedicated to their mission, and they worry about what’s going to happen if everybody leaves,” said the USAID employee.

“There’s a lot of fear that if people take the deal, the rug can be pulled out from underneath them.” —anonymous USAID employee

A supervisor who has worked for the Food and Drug Administration for 13 years said, “It was a slap in the face. I work with scientists, doctors, and very educated people, so the fact that there’s this picture being painted that we’re sitting on our couch eating chips or something, is just so far from the truth, and also really insulting.”

The supervisor told The Free Press that she isn’t taking the offer. “I didn’t work this hard to leave on someone else’s terms, and I think a lot of my colleagues feel the same. But others are less inclined to want to deal with this if they can just get another job somewhere else in private practice.”

Indeed, of the two dozen federal employees The Free Press heard from, only five said they are considering the offer. They cited two reasons: Some lived too far from their office to return to their building full-time—something Trump has demanded in another executive order. Or they were already nearing retirement anyway, so the buyout was, in essence, free money.

For instance, a lawyer who has worked for a federal agency for over 12 years and was close to retirement told The Free Press that she decided to take the deal even though she disagrees with President Trump using deferred resignation as a tool to cull the federal workforce.

“Last year, I probably worked 14 to 16 hours a day for months on end on a case I was working on,” she said. “I think this is a very blunt and stupid tool, and the government is going to lose a lot of the best, most hardworking people.”

Instead of planning a retirement party, she is leaving the government workforce on a sour note. “It doesn’t feel very good. It’s insulting.”

Another insult could be found on the OPM’s Frequently Asked Questions page. Answering an FAQ about whether those who took the buyout could get a second job while still being paid by the government, OPM said, “Absolutely!. . . The way to greater American prosperity is encouraging people to move from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.” [Emphasis added.] One USAID employee described that description as “degrading.”

All of which helps explain why so few of the more than 2 million eligible federal employees have elected to take the deal so far. On Tuesday, Axios reported that only about 20,000 employees have agreed to resign, far fewer than five to 10 percent of the federal workforce the administration was aiming for. (In a statement to The Free Press, OPM spokeswoman McLaurine Pinover said that number “isn’t current” and that the number of deferred resignations continues to increase.) Unless the numbers increase significantly, the Trump administration says there will be widespread layoffs throughout the federal government.

Another issue dogging the program is that many, if not most, federal employees don’t really believe OPM is calling the shots. “Folks don’t believe this is coming from the Office of Personnel Management,” said a director who worked at the Department of Agriculture for 18 years. “They’re seeing it like, this is DOGE, and it’s coming from Elon Musk, who might not really have the authority to be making these promises to people.” And they wonder if Musk understands the complexities of implementing such a sweeping change in the federal bureaucracy.

Then there’s the question of whether the deal is even legal. Daniel Rosenthal, an employment lawyer who often represents unions, told The Free Press that “There’s no statute or law that governs deferred resignation. It’s not something that’s been done before, so we can only really theorize about how potentially it might be enforceable, but there isn’t any precedent that anyone can point to on how to enforce this.”

In an email to The Free Press, Pinover said that employees who take the deal will sign a contract “that provides binding assurance they will not be subject to future RIFs [Reductions in Force], not be expected to work, and their pay will be protected even if there is a lapse in appropriations.”

But Rosenthal, who has read the contract, pointed out some potential holes. ”There’s a provision in there that states that once the employee signs the contract, the employee cannot rescind that agreement, but that the agency head can rescind it, with the employee having no recourse to challenge that. So whenever you have a contract where one side could just decide to cancel it, and the other side can’t do anything about it, I think that’s questionable.”

Only one employee who spoke to The Free Press said he felt like the government’s reduction of force was a good thing. And he had been planning to retire next month.

“I have watched the government grow over the last 20 years, we got $29 trillion in debt, and we’ve got to get that under control for our country.” He accepted the buyout.

Last month, catastrophic fires upended California’s progressive political consensus. This week on Breaking History, Eli Lake traces the failures of far-left governance back to 1970s San Francisco—where the Golden State’s ruling coalition was born. Listen to the episode below or wherever you get your podcasts.