The Free Press

On January 29, Donald Trump issued an executive order to deport resident noncitizens in America who display support for foreign terrorist groups. The president directed federal agencies to identify those who “joined in pro-jihadist protests” on campuses and elsewhere in the recent past. “We will find you and will deport you,” President Trump said.

Ilya Shapiro, a constitutional scholar at the Manhattan Institute, and Robert Shibley, special counsel at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, are normally allies when it comes to freedom of expression. But on Trump’s plan to crack down on pro-Hamas foreign students, they sharply disagree.

Shapiro is in favor of the order, arguing that the federal government has the power to decide who gets to live and study in America. Shibley takes a different view, arguing that these measures will have a chilling effect on speech.

The following is their debate on the topic. Is the executive order constitutionally sound? Will it reduce antisemitism on campus? Will anyone actually be deported? Let’s get into it.

Ilya: It’s odd that I find myself on the other side of a debate over free speech to my friends at FIRE. Usually we are side by side in the fight for the First Amendment. But as with the other rare disagreements I have with them—such as over the forced divestiture of TikTok—it’s because this dispute over President Trump’s executive orders on antisemitism don’t actually have much to do with speech.

Robert: Well, President Trump certainly thinks the orders have to do with speech. The White House’s official fact sheet spells it out: “To all the resident aliens who joined in the pro-jihadist protests. . . we will deport you. I will also quickly cancel the student visas of all Hamas sympathizers on college campuses, which have been infested with radicalism like never before.” Protests and expressions of sympathy are certainly forms of speech.

More specifically, a January 20 executive order is intended in part to ensure that foreigners in the U.S. “do not bear hostile attitudes toward its citizens, culture, government, institutions, or founding principles, and do not advocate for, aid, or support designated foreign terrorists and other threats to our national security.” Advocacy, bearing hostile attitudes—that’s speech.

And the follow-up January 29 executive order directly targets antisemitism, including on campus. It asks agencies to recommend ways to help colleges “monitor for and report activities by alien students and staff” and help “ensur[e] that such reports about aliens lead, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, to investigations and, if warranted, actions to remove such aliens.” Similar efforts aimed at American citizens would certainly violate their free speech rights.

Ilya: However you want to characterize what Trump says, it’s not about speech, but about visas and immigration vetting. We get to decide who gets to come and study in the U.S. As I wrote for The Free Press in November 2023, “although foreigners can’t be punished for speech any more than citizens, there can be repercussions for affiliating with certain groups or calling for violence.” Existing law already allows the government to enforce exactly what Trump’s executive orders direct federal agencies and grantees to do. For example, the Immigration and Nationality Act allows the denial or revocation of a visa for any alien who “endorses or espouses terrorist activity or persuades others to endorse or espouse terrorist activity or support a terrorist organization.”

Moreover, the INA’s inadmissibility provision empowers the president to “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens” who he determines to be “detrimental to the interests of the United States,” or impose on them “any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.” The Supreme Court upheld that broad grant of presidential discretion to vet, restrict, and even ban immigrants—and thus to direct executive-agency action in that regard—during the first Trump administration at the culmination of the high-profile “travel ban” litigation. Trump’s executive orders are in keeping with this legislation, and the broad powers the government has to vet who gets to come to the United States as well as remove the visas from people already here. The First Amendment does not change any of that.

Robert: Even if we have that prerogative, it doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. For most purposes, foreigners in the U.S. have the same First Amendment rights as everyone else. We generally think that’s good. Dissidents from Garry Kasparov to the Dalai Lama have the legal right to speak in America on issues for which they’d face prosecution (or worse) in other countries.

The problem gets worse when the restrictions are used not merely to deny visas but to deport those already here. What university can operate smoothly if international students in class with Americans have to run for cover whenever controversial issues arise? Others may be attracted to a movement after they get here. Is it fair to tell a 19-year-old foreign student that “free expression” in America means they will get shipped back home if Americans infect them with unpalatable ideologies?

The flip side of America’s openness is that some of those foreigners will either be hostile to free speech or engage in speech we don’t like, including antisemitic (but not criminal or legally harassing) speech. But there are also real costs to deporting people in the name of fighting antisemitism. It’s unlikely to persuade them—or others—that they’re wrong, while giving both the deportee and their American acquaintances another grievance to blame on “the Jews.”

Ilya: I have to disagree and—to paraphrase J.D. Vance’s comment to Margaret Brennan—it doesn’t matter whether the foreign student comes radicalized or gets “infected” here. It’s properly the job—the duty—of the state to screen out visitors and migrants who would be harmful to our country, including those who reject our values or who are hostile to our way of life. It’s one of the basic functions of government in a free society.

Those whose visas can be denied for being Communists or Nazis or Islamists—when I obtained my green card, and again when I naturalized, I had to affirm that I wasn’t affiliated with those “or any other totalitarian party”—can also have visas revoked. To give another example in a different context, in 2020, a thousand Chinese nationals had their visas revoked after a presidential proclamation deemed them a risk to national security. President Biden defended that action, signed in the first Trump administration, in court, successfully getting a class-action lawsuit against it dismissed.

Robert: There’s a big difference between foreign nationals with ties to the Chinese military and foreign nationals who join an anti-Israel protest. But I would caution both supporters and opponents of these measures against getting too excited. There are plenty of provisos in the operational text of the orders: “as appropriate and consistent with applicable law,” “if warranted,” and so on. And the law they’re based on is a self-negating rats’ nest. It bans anyone who “endorses or espouses terrorist activity” or was ever a Communist Party member, while also saying people may not be excluded if their “beliefs, statements, or associations would be lawful within the United States.” So the effects of these orders are far from clear.

Campuses do not need another excuse to police speech. What they need is a commitment to treat every student equally. Everyone affected by campus antisemitism has one complaint in common: the gross application of double standards, tolerating behavior toward Jews that would never be tolerated toward some other minority groups. Pro-Palestinian students sometimes have the same complaint, and they’re also right. This, despite decades of harassment training and DEI efforts.

Ilya: This isn’t about policing speech, but about removing those who harass, intimidate, and vandalize, or who support or incite violence. It shouldn’t be controversial that foreigners who interfere with an educational institution’s core mission can and should be removed. Nobody is going to be sent to jail for bad speech, but long before the new executive orders, the State Department confirmed to then-Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) that it can revoke the visas of Hamas supporters. Trump’s now acting on that, which is sensible and responds to the ongoing crisis in higher education and the illiberal winds in our broader culture.

Robert: You won’t find any argument from me about the damage caused by those illiberal winds! But the best way to avoid bad endings is to avoid bad beginnings. FIRE has long advocated legislative and executive action that would permanently protect Jewish and Israeli students (and others) without risking free expression, and that can’t be revoked or retargeted at the stroke of a pen. This is one area where Congress should act, but in the end, it is campuses that need to change their attitudes. Rules and laws can only do so much.

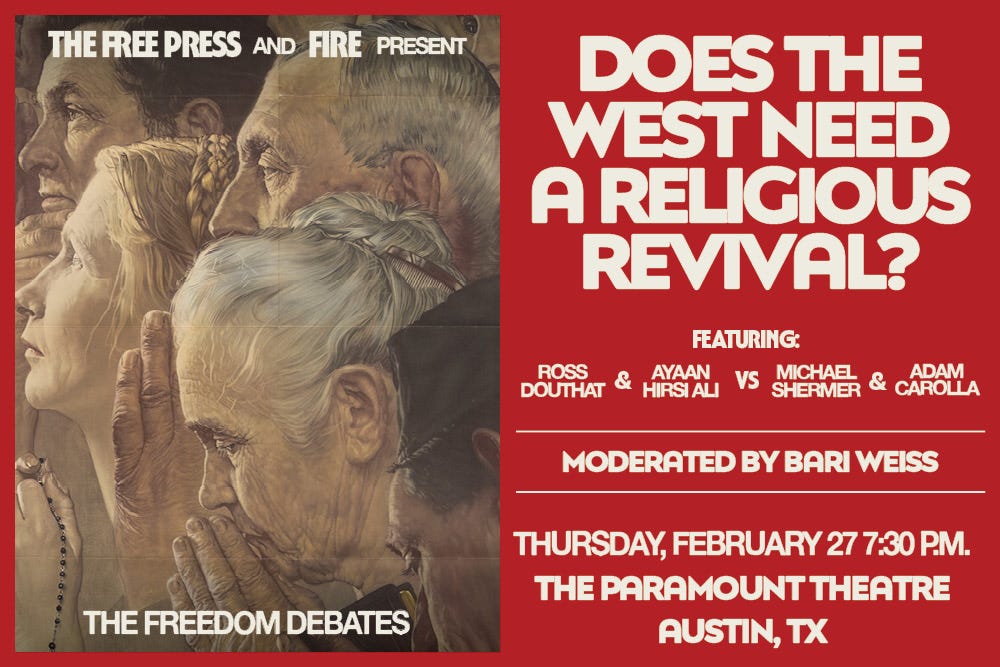

Can’t get enough Free Press debates? This year, we’re partnering with FIRE to present The Freedom Debates, four live debates in cities across the country inspired by FDR’s four freedoms. Up first, in Austin, Texas: freedom of worship.

On February 27 at the Paramount Theatre, Bari Weiss will moderate as debaters duke it out over the question: Does the West Need a Religious Revival? Buy your tickets here.