The Free Press

Today, the state of Missouri is scheduled to execute a man who St. Louis’s top prosecutor says is innocent.

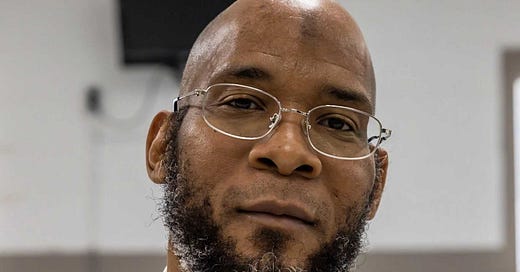

The Missouri Supreme Court refused Monday to issue a stay of execution for Marcellus Williams, 55. Republican Governor Michael Parson also refused to pardon him. Unless the U.S. Supreme Court gives Williams a last-minute reprieve, he will die by lethal injection at 6 p.m. central time today.

Williams was convicted of first-degree murder in 2001 for the murder of Felicia Gayle, a former St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter. Gayle was 42 at the time. The suspected motive was robbery; her husband’s laptop was missing when her body was discovered at home.

But there’s no DNA evidence to back up his conviction, and the witnesses who testified against Williams can’t be trusted, prosecutor Wesley Bell said in a January motion to vacate Williams’s conviction.

Bell also accused prosecutors of having potential black jurors removed from the jury in the trial, which revolved around a black man accused of stabbing a white woman 43 times.

Bell, who did not oversee Williams’s case when he was originally prosecuted 23 years ago, was hardly alone in questioning Williams’s conviction. In August 2017, the last time Williams was on the cusp of being put to death, Missouri’s Republican Governor Eric Greitens stayed the execution and appointed a “board of inquiry” to look into Williams’s case.

But in June 2018, Greitens was forced to step down from office after being charged with campaign finance fraud and sexual assault. (Greitens has never been convicted of anything.) The new governor, Parson, dissolved the board of inquiry, paving the way for Williams’s execution at the state prison in Bonne Terre.

Parson, a former sheriff, has so far refused to offer clemency to anyone on death row. Since he took office in 2018, 11 people have been executed. Missouri ranks No. 3 in the nation when it comes to executions from 2019 to 2023, behind only Oklahoma and Texas, which have put a total of 39 inmates to death during that time period.

Last week, the conservative Missouri Catholic Conference wrote to Parson urging clemency in Williams’s case. “The death of Felicia Gayle is a great tragedy, but the execution of Mr. Wiliams, rather than acting as a salve to the victim’s bereaved loved ones, would be a new tragedy of its own,” Jamie Morris, the conference’s executive director, wrote in a letter that was shown to The Free Press.

Curtis Wichmer, legislative analyst with the conference, was not optimistic. “It seems that the governor of Missouri is trying to end the death penalty in Missouri by exhausting the list of death row inmates,” Wichmer told me. There are 10 people on Missouri’s death row. The state has executed nearly 100 people since 1976, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that capital punishment was constitutional. The last person executed was David Hosier, in June, for murdering a woman he had been seeing.

The Williams case is reminiscent of another case, which The Free Press’s Rupa Subramanya reported on earlier this year—that of Richard Glossip, in Oklahoma.

Almost everyone agrees that Glossip, like Williams, is probably not guilty. And nobody seems able to do anything to stop either from being executed. Glossip has been scheduled to die nine times. The Supreme Court is next scheduled to consider his case on October 9.

As in Oklahoma and elsewhere across the nation, a growing chorus of right-wing voices are voicing skepticism about the death penalty—which conservatives once widely accepted. In January, Republican state legislators in Missouri, defying the governor, publicly announced their opposition to capital punishment. State Representative Chad Perkins introduced legislation that would abolish it.

“Anyone who says they’re pro-life should feel a little conflicted on this topic—because if you’re pro-life, then I think you’ve got to look at it and say you’re that way from the beginning to the very end,” Perkins said at the time. “And I don’t think that the government should have a monopoly on violence.” Governor Parson has not commented publicly on anti-death penalty voices in his own party.

Wichmer was cautiously optimistic that an anti-death penalty faction was growing in Missouri and elsewhere. “As more people are executed, I think there will be more conservatives who realize, ‘Hey, this keeps happening—is this something we should have the state do?’ ”

Peter Savodnik is a writer and editor for The Free Press. Follow him on X @PeterSavodnik, and read Rupa Subramanya’s piece, “Can This Death Row Inmate Bring Down the Death Penalty Itself?”

To support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

I can’t believe The Free Press would publish an article like this. This is the level of “reporting” I’d expect from The Guardian, not a newsletter striving to provide old school, fact based, investigative journalism.

I'm very disappointed. The Front Page said this would be a "full analysis," which I very much wanted. Knowing that Bell is anti-death penalty and won on a platform of ending "mass incarceration," for instance, might give a different gloss on the fact that the prosecutor's office supported reversing the conviction. No information is provided about why Williams was convicted, aside from the claim that the witnesses were untrustworthy. The current governor's decision not to pardon him is questioned because he's a former sheriff, an ad hominem attack that I wouldn't expect here.

Try again, please. A charge of executing an innocent man is a serious one, and deserves careful attention. As it happens, my son is preparing for a debate in his homeschool class on whether to abolish the death penalty; I'd love for him to have some fresh evidence to work with.