The Free Press

A.J. Jacobs has become famous for coming up with great ideas and taking them way too far. While researching his best-selling 2007 book, The Year of Living Biblically, he literally followed every single rule in the Bible, growing a huge beard and avoiding clothes made from two kinds of fibers. For Drop Dead Healthy in 2012, he tested every diet and exercise regimen he could find, on a two-year quest to become “the healthiest man alive.” He wrote parts of the book while walking on a treadmill, experimented with “extreme chewing,” completed his first sprint triathlon, and lost more than 20 pounds.

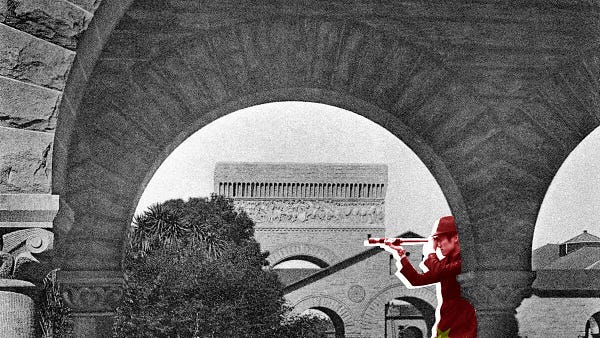

This past May, A.J. published The Year of Living Constitutionally. His latest extreme mission was inspired by Supreme Court rulings in 2022 on women’s rights and gun rights, which ignited a national conversation about how to interpret the Constitution—and A.J. decided to find out what would happen if he interpreted it as literally as possible. He exercised his right, as an American citizen, to bear an eighteenth-century musket in the streets of New York. He quartered soldiers in his apartment, much to his wife’s consternation. And—as he describes in the following piece—he petitioned Congress to become a state-sanctioned pirate, otherwise known as a “privateer,” with permission to detain enemy ships.

Privateers are the unsung heroes of the American Revolution. We probably wouldn’t celebrate the Fourth of July without them. So, while A.J. acknowledges parts of his experiment are absurd, his goal is a serious one: to fully understand, and therefore preserve, the democracy that was founded on this day 248 years ago. It’s a goal we admire at The Free Press. So this holiday, we bring you A.J.—tricorn hat, musket, and all—on the art of living constitutionally.

It’s important, on today of all days, to be grateful for our constitutional rights—not only the right to free speech and the right to free exercise of religion but also the underappreciated rights. Like your constitutional right to become a government-sanctioned pirate.

It may not get much publicity, but there it is, smack-dab in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution: Congress has the power to grant citizens “letters of marque and reprisal.” Meaning that, with Congress’s permission, private citizens can load weapons onto their fishing boats, head out to the high seas, capture enemy vessels, and keep the booty. Back in the day, these patriotic pirates were known as “privateers.”

At the start of the Revolutionary War, America had a meager navy, so we had to rely on these privateers, who captured nearly two thousand British vessels and confiscated vast amounts of food, uniforms, weapons, and barrels of sherry. They included Jonathan Haraden, who captained several vessels, including the delightfully named Tyrannicide. He once fought three British ships at once off the coast of New Jersey—and captured all of them.

The Founding Fathers were big fans of privateers. Late in life, John Adams wrote glowingly about the 1775 Massachusetts law that first legalized them, calling it “one of the most important documents in history. The Declaration of Independence is a brimborion in comparison with it.” You read that right: in Adams’ opinion, a law authorizing patriotic piracy is much more important than that trifling tidbit about “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The trouble is, Congress has not granted permission to become a privateer to any citizen since 1815. So, a few months ago, I set out on a quest to become the first constitutionally approved privateer in 209 years.

The quest was, in part, research for my new book, The Year of Living Constitutionally, which was inspired by the heated contemporary debate over how America should interpret its Constitution. The majority of justices currently sitting on the Supreme Court are originalists: they believe the most important consideration in interpreting the Constitution is what it originally meant when it was ratified in 1789. I wanted to find out what would happen if I attempted to become the ultimate originalist—engaging with the document as a brand-new eighteenth-century citizen of the United States might have.

But when I first considered applying to Congress for “letters of marque and reprisal,” I was a little stumped. Should I write them a quill-penned missive? Should I trek from my home in New York City down to Washington, D.C., on horseback? A few weeks later, providence offered an opportunity.

In the past, I have donated to the Democratic National Committee, so I occasionally get fundraising emails from the offices of congresspeople all over the nation. And shortly after my project began in 2023, I received an email from an aide to Rep. Ro Khanna, a Democrat from Silicon Valley, saying the congressman was coming to New York and would love to meet me, I suppose because of my past generosity. I’ve always ignored such requests, but now there was something I needed.

“It would be my honor,” I replied.

So a few weeks later, I arrived in the lobby of a Midtown hotel for my meeting. The congressman’s aide, Cooper, led me to the table, and there was Khanna—a tall, good-looking, rising star of the Democratic Party; a Yale Law School graduate focused on climate change and artificial intelligence governance.

We shook hands, and I explained I wanted to ask him “one quick thing.”

“Please,” said the congressman.

I forced myself to speak the words, reminding myself of my commitment to live by the Constitution’s original meaning in 2024.

“I brought you this. It’s an application to get a letter of marque from Congress. I’m interested in becoming a privateer.”

I handed the congressman a piece of paper on which, in an old-timey font, I had evoked what is my right, according to Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution. He examined it for a couple of seconds, then asked: “How do we do this?”

I loved Representative Khanna’s optimism, his let’s-make-this-work attitude. He was on board even before he really understood what I was asking.

I explained that every American had the right to seek approval to “detain and seize any seafaring vessels considered to be operated by enemies of the United States.”

“Are you going to the Taiwan Strait?” Khanna asked, incredulous.

“Yeah, if you want me to.”

“Wow,” he said.

I couldn’t tell if it was a Wow, this is cool, or a Wow, this is what I have to put up with to raise money. “It has to be voted on by the whole Congress?”

“I think so.”

“We will look into it,” Khanna said, then held up my letter: “Can I keep this?”

For several minutes, we spoke about originalism and the Constitution. Though it’s obscure, the privateering clause highlights that this document—for all its brilliance and prescience—was written in a vastly different time. Some passages—such as those about the “blessings of liberty” and “equal protection”—are timeless. But others are clearly the product of the eighteenth century. For more proof that the Constitution is a historical document, please see the Third Amendment, which is about quartering soldiers.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be grateful to the Constitution. We should. It made possible not just privateers but also our most basic liberties. But we should also be grateful we don’t interpret it as it was written in the eighteenth century. Back then, for instance, free speech was far more constrained (there were numerous state laws banning blasphemy), and putting a man in the pillory was considered neither cruel nor unusual punishment.

I’m also not saying we should ignore the dated parts of the Constitution. Article I, Section 8 reminds us about a crucial part of our history: privateers are rarely given their due, perhaps because their own patriotism was mixed with the motive of profit. But they deserve credit, especially at a time when Americans seem increasingly unwilling to serve their country.

I am not one of those Americans. Over the last year I have exchanged several emails with Cooper, Rep. Khanna’s aide, who now addresses me as “Captain.” He says Khanna is discussing getting me a letter of marque with his colleagues. In the meantime, I have found my own vessel: my friend’s 23-foot waterskiing boat. All I need to become a state-sanctioned pirate is for the majority of congresspeople to sign off on my request. Right now, they seem a little distracted with other matters.

But I still have my tricorn hat, ready and waiting. I’ve told Cooper I’m standing by, ready for updates, prepared to serve. But I feel I have already done something patriotic, in raising awareness for privateers, these unsung heroes of American independence—even if I myself never get to hit the high seas.

A.J. Jacobs is an author, journalist, lecturer, and human guinea pig. His new book is “The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution’s Original Meaning.” Follow him on X @ajjacobs, and find him on Substack at “Experimental Living with A.J. Jacobs.”

Here at The Free Press, we believe deeply in America and its promise. If you share our values, subscribe today:

Pirate vs privateer? Privateer connotes some governmental approval with an okayed cause at play. Pirate? Well let's see now, how about the Somali pirates that plague waterways and mariners. But good on you for your effort! I look forward to reading your book (& the others as well).

Actually it might not be a bad idea for some "privateers" to take on the Houthis in the straits. Make them look over their shoulders for a change.