The Free Press

The following essay by Coleman Hughes is the longest we have ever run at The Free Press, and it deserves a few additional words of introduction.

Back in January, you may recall that Coleman published a column in these pages called “What Really Happened to George Floyd?” which took stock of a documentary about the death of George Floyd and the trial of Derek Chauvin. In the months that followed, the journalist Radley Balko wrote a three-part, 30,000-word essay tearing into Coleman’s 2,000.

One reason Coleman’s essay is so long is that he is responding to the many charges of factual and interpretive error leveled against him by Balko. There are also a lot of facts to cover, and a good deal of context, from medical examiner reports to police training manuals. But there is another reason for the length of Coleman’s important piece.

Balko’s critique, though styled as an exhaustive set of granular corrections of the factual record, was made in the service of refuting a claim that Coleman did not make about Derek Chauvin’s innocence.

The nature of this misunderstanding is important. As Coleman patiently explains, the asymmetry of their approaches grows out of his own focus on the concept of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. In a criminal trial, this does not simply allow for the presentation by the defense of possibilities that may or may not prove true—since truth is never a foregone conclusion—it demands their consideration by the jury. And it tasks the prosecution with the burden of dispelling the shadows of doubt so vital to protecting the rights of the accused, whoever they may be.

Radley describes a still larger purpose of his essays this way: “But this also isn’t just about Hughes’s column, or the documentary. It’s about an insidious counter-narrative that has been picking up momentum on the far right for months, and is now seeping into more mainstream outlets.”

Mischaracterizing Coleman’s review as an argument for Chauvin’s innocence (it was not; it was an argument that Chauvin was not proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt) allows Radley to treat it as part of an insidious “counternarrative” derived from the “far right.” In other words, Coleman’s good-faith effort to understand Floyd’s tragic death, the challenges of policing, the role of race and media, and the tangled complexity of criminal and social justice in our contentious, narrative-saturated moment are recast by Radley as something else—something dangerous.

Coleman announced his intention to wait until all three parts of Radley’s essay were posted before responding, but he invited Radley to debate him at The Free Press or on his own podcast in the interim. Radley refused—unless Coleman immediately published corrections of facts whose accuracy and interpretation were to have been the subject of the debate. These clarifications are provided in Coleman’s essay below, which also restores the context in which they were discussed.

Radley’s statement about “insidious counternarratives” continues: “Hughes’s article—and the reaction to it—shows how the claims made in TFOM [the documentary] are being laundered through more respectable, ‘heterodox’ media outlets, podcasts, and pundits. Hughes himself just published a book, and was flatteringly profiled in the New York Times. He was on Bill Maher’s show, and will be moderating a panel discussion on Gaza (of all things) in New York later this month.”

Leave aside for the moment Radley’s insulting surprise that Coleman might moderate a discussion about Gaza. The vehemence and volume of Radley’s attack, with its whiff of conspiracy and presumption of bad faith, doesn’t just argue for Chauvin’s guilt, but for the complicity of Coleman, The Free Press, and all who approach the story in a manner at odds with his own understanding, if only by leaving room for a gray zone where he sees black and white.

In a tweet following the first installment of his essay, Radley wrote:

“Yesterday I demonstrated how Coleman Hughes amplified the lies about George Floyd’s death churned out by a nutty, conspiratorial ‘documentary’—making him either complicit or a dupe.”

In Balko’s binary understanding, Coleman is either a conspiracy nut or a fool. Though the last line of the tweet—“Today, Hughes got a flattering, book-hawking profile in the NYT”—seems the most telling. For anyone to take his work seriously, or perhaps especially to grant him safe passage through the pages of The New York Times, is an affront to Balko’s own Manichean vision.

I could go on, but let’s get to Coleman’s essay. This piece—and all of his work—is respectful of the gray zones. Examining plausible alternatives that may or may not prove true is not only the way our judicial system protects the accused from ideological conviction. It is also useful for journalists, especially in an overheated and partisan age where truth is often the first casualty. —BW

In January, I wrote an essay for The Free Press provoked by a new documentary called The Fall of Minneapolis. In the essay, I argued that Derek Chauvin’s conviction for felony murder in the case of George Floyd was erroneous. There was reasonable doubt, I argued, on two elements of the crime: felony assault and cause of death. Furthermore, I argued that the fairness of the trial was compromised by jury bias, by fears for personal safety in the event of Chauvin’s acquittal, and by a more general fear of rioting in the event of an acquittal.

In response to my piece, Radley Balko, a former Washington Post columnist who focuses on criminal justice and civil liberties issues, wrote a three-part response on his Substack, as well as a shorter “update” post between parts two and three. He has also written a follow-up piece in The UnPopulist, summarizing his arguments.

All told, Balko has written over 30,000 words lambasting my piece, the documentary, and what Balko calls “far-right punditry” on policing issues—which Balko treats as three examples of the same worrisome trend.

Balko’s series plays fast and loose with the distinction between claims made by me, the documentary, and “far-right pundits”—three very different entities. To choose just one example, in his first piece, he writes: “The Free Press feels like new territory for these conspiracies,” referring presumably to a “conspiracy” to convict Chauvin.

But my Free Press piece did not allege or even imply a conspiracy. A conspiracy is when two or more people get together to do something unethical or illegal. What my essay alleged was quite different and far less sensational: that Chauvin did not get a fair trial. There was jury bias on the substantive issue of police use of force, fears for safety in the event of an acquittal, and fears of destructive riots in the event of an acquittal—claims that Balko has not even tried to refute in his many thousands of words.

I pointed out, for instance, that a BLM sign was found displayed prominently in the window of one juror’s home. I should have also added the fact that one juror, Brandon Mitchell, was photographed at a protest commemorating Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech during the summer of 2020. At that protest, two of George Floyd’s family members addressed the crowd, and Mitchell was wearing a t-shirt with a picture of King and the words: “GET YOUR KNEE OFF OUR NECKS” and “BLM.”

That’s hardly an allegation of conspiracy. But it is prima facie jury bias.

I invited Balko on my podcast to debate these issues. To mitigate the possibility of “home field advantage,” I told him that he could record the whole conversation and release it independently. He declined. Free Press founder Bari Weiss offered to organize a debate, which Balko also declined. Finally, Liz Wolfe from Reason magazine’s Just Asking Questions podcast messaged me offering to host a debate between Balko and me in which she would be a “neutral party.” We both agreed, though the resultant debate was closer to a 3-on-1, with Wolfe and her co-host functioning more like participants on Balko’s side than moderators. (You can judge for yourself.) It was therefore not the best venue for me to defuse all of the misinterpretations of my arguments.

The purpose of this essay is to set the record straight on Balko’s claims, which range from useful counterarguments to misleading assertions and outright errors. Our disagreements fall into two basic categories: the first is the question of how exactly Floyd died. And the second pertains to whether or not Chauvin was following his training.

One final, important note before I dive in: Balko’s series generally mischaracterizes my essay as arguing for the definite truth of various propositions—or doing a “just asking questions” routine—when in fact I was arguing for the existence of reasonable doubt.

In a typical debate, each side is trying to prove a claim by summoning more evidence than the other side—“guns are helpful” vs. “guns are harmful,” for instance. The burden assigned to each side is symmetric. If either side summons more evidence than the other, then that side wins.

Criminal trials are deliberately not like this. They are highly asymmetric—and that’s intentional.

It’s not enough for a majority of the evidence to indicate guilt. And it’s not enough if the defendant’s guilt is “highly and substantially more likely to be true than untrue.” That is the “clear and convincing evidence” standard.

Rather, “beyond a reasonable doubt” means that “there is no other reasonable explanation that can come from the evidence presented at trial” other than the defendant having committed the crime in question. Keep that phrase—no other reasonable explanation—at the top of your mind. My Free Press piece was written from the perspective of reasonable doubt. In the essay, I summed up my thesis like this: “In short, there are two major justifications to reasonably doubt Chauvin’s felony murder charge: whether he caused Floyd’s death and whether he committed a felony.”

There remains significant uncertainty about the death of George Floyd—uncertainty that was not settled at trial. My purpose in this essay, as in my original column, is not to settle that uncertainty for good by putting forward a definitive version of events—that is not the defense’s burden anyway. My purpose is to convey the existence of other reasonable explanations.

With that throat-clearing out of the way, let’s move on to Balko’s substantive arguments.

Part One: The Autopsy

In Chauvin’s criminal trial, the prosecution brought three counts against him: second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. What all three counts had in common was the requirement to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Chauvin’s actions were a “substantial cause” of Floyd’s death.

The way that the prosecution went about this was by arguing for a specific theory of Floyd’s death: that the amount of weight that Chauvin put on Floyd’s neck and back, and the length of time that the weight was there, combined to prevent Floyd from taking full breaths, which caused him to die of low oxygen. The prosecution’s key witness on this point was Dr. Martin Tobin. I’ll refer to this as the “positional asphyxia theory.”

But the official autopsy of George Floyd—conducted by Hennepin County medical examiner Dr. Andrew Baker—advanced a different theory. Baker’s theory did not implicate Chauvin and did not involve positional asphyxia. Rather, his theory was that the subdual (the hold), restraint, and neck compression led to an adrenaline surge, which in turn made demands on Floyd’s heart that it could not meet—because of his underlying diseases and because of the fact that he was on multiple drugs at the time, including fentanyl and methamphetamine. I’ll refer to this as the “adrenaline surge theory.”

Here’s how Dr. Baker explained it in his testimony:

In my opinion, the physiology of what was going on with Mr. Floyd on the evening of May 25th is, you’ve already seen the photographs of his coronary arteries, so that you know—you know he had very severe underlying heart disease. I don’t know that we specifically got to it, counselor, but Mr. Floyd also had what we call hypertensive heart disease, meaning his heart weighed more than it should.

So, he has a heart that already needs more oxygen than a normal heart by virtue of its size, and it’s limited in its ability to step up to provide more oxygen when there’s demand because of the narrowing of his coronary arteries. Now, in the context of an altercation with other people that involves things like physical restraint, that involves things like being held to the ground, that involves things like the pain that you would incur from having your—you know, your cheek up against the asphalt and abrasion on your shoulder, those events are going to cause stress hormones to pour out into your body, specifically things like adrenaline.

And what the adrenaline is going to do is, it’s going to ask your heart to beat faster. It’s going to ask your body for more oxygen so that you can get through that altercation. And, in my opinion, the law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression was just more than Mr. Floyd could take by virtue of that—those heart conditions.

Upon cross-examination, Dr. Baker explained it more succinctly, adding the drugs in Floyd’s system as a contributing factor as well (he had also listed drugs as a contributing cause in his autopsy report):

[Floyd] experienced a cardiopulmonary arrest in the context of law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression. It was the stress of that interaction that tipped him over the edge given his underlying heart disease and toxicological status.

Balko omits Dr. Baker’s adrenaline surge theory from his discussion. Even worse, he mischaracterizes Dr. Baker’s theory, calling it “a (somewhat garbled) description of positional asphyxia.”

It was not. It was a different theory altogether. Dr. Baker explained his cause of death under oath and in detail—never citing positional asphyxia or Floyd’s difficulty getting full breaths at any point.

Dr. Baker’s adrenaline surge theory does not implicate Chauvin. Per this theory, the arrest in general was causally significant because it led to Floyd’s high-adrenaline state. The fact of the police hold and the struggle in general were causally important for the same reason.

In other words, Dr. Baker was not alleging a coincidental death. It was the altercation with Chauvin that triggered Floyd’s spike in stress hormones. But, according to Dr. Baker, it was not Chauvin’s weight on Floyd’s back that restricted his breathing.

It’s not only my view that the adrenaline surge theory did not implicate Chauvin. It was also the implied view of the prosecution. In their closing argument, the prosecution rejected the adrenaline surge theory—making clear that they sided with Dr. Tobin’s “positional asphyxia” theory:

No question [Floyd] was experiencing stress even before the officers shoved him onto the sidewalk unnecessarily, gratuitously, disproportionately. But none of this caused George Floyd’s heart to fail. It did not. His heart failed because the defendant’s use of force—the 9 [minutes] 29 [seconds]—that deprived Mr. Floyd of the oxygen that he needed, that humans need, to live. And Dr. Tobin knows because he is a pulmonologist. . . . He’s the only person who testified who’s able to calculate lung capacity. . . Dr. Baker couldn’t do it. . . . He deferred to the pulmonologist. . . Dr. Tobin literally wrote the book on the subject. . . what he was able to observe was oxygen deprivation, was asphyxia.

It is very likely that the prosecution rejected Dr. Baker’s “stress” theory (summarily and without evidence) because they understood that it didn’t implicate Chauvin—whereas the positional asphyxia theory did.

To sum up, there were two different theories of what caused Floyd’s death: the positional asphyxia theory (Tobin) and the adrenaline surge theory (Baker). To be clear, I’m not definitively siding with one over the other. Nor am I arguing that Chauvin “could not have killed Floyd,” as Balko has falsely alleged. My argument is that both theories were reasonable. And neither theory was refuted beyond a reasonable doubt by other evidence presented at trial.

As a juror, if you have two reasonable explanations for cause of death—one of which implicates the defendant and one of which does not—then you are supposed to acquit.

With that basic case laid out, let’s look at some of the counterarguments Balko has raised—all of which are red herrings.

First, there is the fact that Dr. Baker’s topline cause of death on his autopsy report was “Cardiopulmonary Arrest Complicating Law Enforcement Subdual, Restraint, and Neck Compression.” According to Balko, the fact that the police restraint and neck compression were listed in the topline cause suggests Chauvin’s guilt. But upon closer examination, it does not.

The topline cause is a vague phrase on its own. But Dr. Baker explained it multiple times during his testimony—in the two passages quoted above. He also explained in detail what he meant by the crucial word complicating, which describes Baker’s view of the relationship between the police hold and Floyd’s death. Baker explained that complicating means “an untoward event on the heels of an intervention.” (Untoward in this context means unexpected.)

To make this explanation concrete, Dr. Baker gave two examples of “complicating” causation: a person who has an allergic reaction to heart medicine, and a person who suffers a blood clot during hip surgery. The basic idea is that A unexpectedly causes B in such a way that it would not tend to cause B in a typical case. (Most people aren’t allergic to heart medicine, for instance.)

For one thing, Dr. Baker’s explanation further highlights his disagreement with Dr. Tobin. Tobin believed that a healthy person would have died if subjected to what Floyd was subjected to. Baker believed the opposite: in Baker’s account, it was only because of Floyd’s severe underlying vulnerabilities and drug intoxication that the “untoward” outcome (the cardiopulmonary arrest) occurred.

By including the “law enforcement, subdual, and neck restraint” on the topline, Baker was not saying that the hold caused Floyd’s death because of the amount of weight and the duration of time—or because it caused shallow breathing. He was merely giving a summary of his distinct theory of Floyd’s death—a theory that the prosecution summarily rejected, likely because they knew that it did not implicate Chauvin.

Dr. Baker’s theory is also relevant to the mens rea elements of two of the charges: third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. According to the jury instructions, the third-degree murder charge required proving that Chauvin acted with “reckless disregard for human life” while committing an act “highly likely to cause death”—the classic example being shooting indiscriminately into a crowd of people without trying to kill anyone in particular. The manslaughter charge required proving that Chauvin “consciously took a chance of causing death or great bodily harm.” In both cases, it had to be proven that Chauvin was consciously aware of huge risks yet took them anyway.

Dr. Baker, however, did not view Floyd’s death as a likely result of that kind of police hold. Rather, he viewed it as an “untoward” outcome—a low-probability, unexpected result that happened only because of Floyd’s severe underlying conditions and toxicological status—akin to having an allergy to heart medication. If true, that undermines the idea that Chauvin must have been consciously aware of taking huge, obvious risks.

Secondly, Balko highlights the fact that Dr. Baker deferred to pulmonologists on lung-specific issues—as if that is tantamount to him deferring to Dr. Tobin’s theory of Floyd’s death in general. A pulmonologist specializes in treating lung conditions. A forensic pathologist specializes in determining the manner and cause of death. So when a forensic pathologist defers to lung specialists on lung-specific issues or heart specialists on heart-specific issues, he is not saying that they should also trump him in his own area of expertise: namely, holistically determining the manner and cause of death. If Dr. Baker meant to say that, he would have said that.

Thirdly, Balko highlights the fact that Dr. Baker testified for the prosecution, implying that his doing so indicates his agreement with the prosecution’s general case. This argument is a bit rich. From a strategic point of view, the prosecution had no choice but to call Baker as a witness—whether or not his testimony was helpful or harmful to their case. For the state to cede him to the defense would be to create the devastating impression that their own forensic pathologist (and the person who did the official autopsy) agreed with the defense’s case. So strategically, they had to call him no matter what. As for Baker, he would have had no choice in the matter once he was subpoenaed to testify.

More to the point (as quoted above), in their closing statement, the prosecution specifically rejected Dr. Baker’s “stress” theory (without explicitly linking it to him). They also downplayed his expertise in favor of Dr. Tobin—hardly an indication of agreement between Dr. Baker and the prosecution.

Finally, Balko argues that because Dr. Baker listed “homicide” as the manner of death, it indicates that he agreed with the prosecution’s case. Balko says that Baker’s choice of “homicide” was “easily the most important finding Baker makes” because this is a “legal determination.”

This is incorrect on multiple levels and easily disproven by Baker’s own testimony.

As Baker explained twice in his testimony, manner of death is not a legal determination, and the word homicide has a much broader meaning in the world of forensic pathology than it does in a courtroom.

So, as a medical examiner, we apply the term homicide when the actions of other people were involved in an individual’s death. It’s one of five manners of death that we can choose from. The other four being accident, suicide, natural, or undetermined. Homicide, in my world, is a medical term. It’s not a legal term. From a vital health and public statistics point of view, it’s critical that medical examiners fill in a manner of death, and that would be a death certificate because from a public health point of view, you want to know how many people committed suicide in your state. How many people died out of accidents in a given year in your state. And so it’s a key piece of public health data, but we don’t use it as a legal term. [bold mine]

On cross-examination, he reiterated the point:

Eric Nelson: Labeling this death as a “homicide.” That is a medical determination that you made, correct?

Dr. Baker: Correct.

Nelson: It is not the same standard as the legal standard, agreed?

Dr. Baker: I don’t even know what the legal standard is, but they’re two different worlds.

For medical examiners, homicide means that other people were involved in a very broad sense. It does not mean that the medical examiner believes that the act clears the legal bar for homicide.

Consider, for instance, the example of Mario Gonzalez—whose death in Alameda, California, in 2021, mirrored Floyd’s in many ways. In Gonzalez’s autopsy report, the forensic examiner listed the main cause of death as “toxic effects of methamphetamine.” (The contributing causes of death were “physiologic stress of altercation and restraint; morbid obesity; alcoholism.”) But despite the fact that drugs were the main cause of death, the manner of death was still listed as a “homicide,” simply because police were involved in the broadest sense: they were holding him in the prone position at the moment he died from meth intoxication.

Whether you agree with this explanation of Gonzalez’s death is beside the point. The important point is that it is coherent for a medical examiner to list the manner of death as “homicide” while also listing drugs as the main cause of death—so long as other human beings were “involved” in a very broad sense. That is how broad the concept of “homicide” is in the lexicon of forensic pathology. So to infer anything of direct relevance to a murder charge from the “homicide” determination is a fallacy.

Finally, Balko has falsely alleged that I’ve argued that Floyd’s death “was likely caused by a drug overdose or heart disease.” I’ve never argued that Floyd likely died of an overdose. The word overdose appears nowhere in my Free Press column. The most charitable explanation of Balko’s misimpression here is that he was confused by my description of Floyd’s postmortem fentanyl levels as “potentially lethal.”

“Potentially lethal,” however, is a straightforward, accurate, and reasonable way to describe Floyd’s postmortem fentanyl levels. The average overdose death has a postmortem fentanyl level of 26 ng/mL. According to Dr. Baker, overdose deaths have been recorded as low as 3 ng/mL. Floyd’s postmortem level was 11 ng/mL. To describe that simply as a “lethal dose” would be to imply that almost anyone would die of it—which isn’t true. To describe it as a “nonlethal” dose would be to imply that almost no one would die of it, which also isn’t true. “Potentially lethal” splits the difference and is therefore a sensible way to describe it.

In the context of my argument, the words potentially lethal were not there to imply that Floyd may have died of an overdose. Rather, they were there to give the reader a sense of how much fentanyl 11 ng/mL is. To a typical reader, the number alone is meaningless. Is 11 ng/mL a trace amount? Is it a dose so big that anyone would die of it? The truth is that 11 ng/ml is about halfway between the average fentanyl overdose death and the low end of fentanyl overdoses.

The reason all of this is relevant is not to build a case that Floyd died of an overdose, but to argue that, if Dr. Baker’s “adrenaline surge” theory was correct, then the drugs in Floyd’s system constituted another contributing element (in addition to his enlarged heart and constricted arteries) that made him vulnerable to death by adrenaline surge.

As for the idea, put forward by Balko, that I claimed that Floyd died of generic “heart disease,” this also appears nowhere in my essay. What I did mention was the cause of death listed in Dr. Baker’s autopsy: “cardiopulmonary arrest” in addition to the specific underlying conditions that Baker found. In this piece, I have expanded on that by quoting Dr. Baker’s more detailed explanation at trial. That detailed theory is not that Floyd died of generic “heart disease” coincidentally at the moment that he was getting arrested. Rather, the theory is that he died during the arrest because the associated adrenaline spike led to a cardiopulmonary arrest due to his underlying vulnerabilities and drug intoxication.

Part Two: The Training

To recap, all three charges brought against Chauvin required proving, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Chauvin caused Floyd’s death. But the most serious charge—second-degree murder—required proving something further: that Chauvin committed a felony assault because he violated his Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) training.

The key point of disagreement between Balko and myself, then, is over whether (or to what extent) Chauvin was following training. Specifically, we disagree about whether Chauvin was performing something called the Maximal Restraint Technique (hereafter MRT)—a technique that involves restraining a suspect who is on the ground and immobilizing their arms and legs. Lots of evidence can be marshaled on both sides of this question. However, by misstating the guidelines in the MPD manual and by omitting much of the training that was not in the manual, Balko drastically understates the strength of Chauvin’s defense.

Before we get to the ways in which Balko misstates and omits important aspects of MPD training, one point of clarification is in order. In my exchanges with Balko, I never got perfect clarity on whether he was arguing that (1) Chauvin’s hold was improper MRT, (2) or Chauvin’s hold was not MRT at all. He can be read as arguing either one of these at various points.

However, not even the prosecution argued that what Chauvin was doing wasn’t MRT at all. In the prosecution’s closing argument, Steven Schleicher said of the MPD officers: “Kneeling on top of someone—on their neck and their back—effectively, they were using a Maximal Restraint Technique, effectively.” Schleicher then went on to list all the ways in which he alleged they were performing MRT improperly. So the first argument—that it was highly improper MRT—is stronger, and I will take it to be Balko’s real point.

To start, Balko argues that MRT is authorized only under certain circumstances, and that Floyd’s arrest did not meet those criteria. In Balko’s view, therefore, the MPD officers were wrong to initiate MRT in the first place. Here’s Balko:

The very first point in the MPD policy manual’s discussion of MRT states that it “shall only be used in situations where handcuffed subjects are combative and still pose a threat to themselves, officers or others, or could cause significant damage to property if not properly restrained.”

George Floyd clearly did not want to be arrested. He argued, pleaded, and filibustered. He passively resisted. He was scared, and was probably high. But it’s a stretch at best to say he posed a threat. He never struck, threatened, or harmed an officer or bystander. The defense claimed Floyd was a threat because of his size and the fact that he appeared to be on drugs. But police officers aren’t permitted to use force on a suspect because he might be a threat. He needs to actually exhibit threatening behavior. [bold mine]

Balko’s analysis is incorrect. As stated in the manual, MRT required that the subject be a threat to others or to themselves—a fact that Balko includes in the passage, but excludes from his analysis:

MRT “shall only be used in situations where handcuffed subjects are combative and still pose a threat to themselves, officers or others, or could cause significant damage to property if not properly restrained.” [italics mine]

Despite accurately quoting the policy, Balko does not consider the argument that Floyd was a threat to himself, and instead focuses narrowly on the part of the policy that talks about being a threat to “officers or others.”

Floyd was certainly a threat to himself. The officers believed (correctly) that Floyd was high on hard drugs. If someone is high on pain-numbing drugs, and that person is resisting arrest, then it is reasonable to worry that they pose a threat to themselves—even if they pose no threat to others. This is because people who are physically resisting and on intense pain-killing drugs are liable to harm their own bodies in ways that they can’t feel in the moment.

But we don’t need hypotheticals to understand why the officers believed that Floyd was a threat to himself. Thomas Lane, the officer who initially arrested Floyd, told agents at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehensions (BCA) that as Floyd was fighting their efforts to get him in the back of the squad car, he saw Floyd banging his head against the glass divider and noticed blood around Floyd’s mouth: “He started really thrashing back and forth, and I think he was hitting his face on the glass that goes to the front seat. That was the first time I saw that he was bleeding from the mouth.” That is the kind of situation in which a reasonable officer might see a person as constituting a threat to themselves, even if they pose no threat to others.

Balko is also incorrect to say that Floyd was only “passively resisting.” Passive resistance and active resistance are technical terms defined in the MPD manual.

Passive resistance: A response to police efforts to bring a person into custody or control for detainment or arrest. This is behavior initiated by a subject, when the subject does not comply with verbal or physical control efforts, yet the subject does not attempt to defeat an officer’s control efforts.

Active Resistance: A response to police efforts to bring a person into custody or control for detainment or arrest. A subject engages in active resistance when engaging in physical actions (or verbal behavior reflecting an intention) to make it more difficult for officers to achieve actual physical control. [bold mine]

Floyd was passively resisting toward the beginning of the arrest. But by the time he was struggling against the officer’s attempts to get him in the squad car, his behavior met the threshold of “physical actions that make it more difficult to achieve actual physical control.” It would be hard to understand the failure of three officers to get Floyd in the squad car if he were only passively resisting.

Certainly, when he got on the ground and delivered a forceful two-legged kick in Officer Lane’s direction—visible at 10:55 in this version of Officer Keung’s bodycam footage and 11:19 in this version of Officer Lane’s bodycam footage—it is hard to understand how his behavior could qualify merely as “passive resistance.”

Next, Balko argues that MRT requires “light to moderate” pressure—whereas Chauvin was using more than moderate pressure:

MPD officials testified at the trial that officers were taught that the MRT requires “light to moderate pressure.” According to the autopsy report, Floyd had bruises and abrasions on his left shoulder and the left side of his forehead, cheek, and mouth. This is the side of his body that Chauvin ground into the pavement. Floyd also had abrasions on his nose.

Balko does not provide a source for the claim that “MPD officials testified at trial that officers were taught that the MRT requires ‘light to moderate’ pressure.’ ” I’m aware of only one MPD official who testified about “light to moderate pressure”—Chief Arradondo—and he was referring not to MRT but to neck restraints, which are a separate technique governed by a separate set of rules:

Steve Schleicher: Well, we read the departmental policy on neck restraints. Is this a neck restraint?

Chief Arradondo: A conscious neck restraint by policy mentions light to moderate pressure. When I look at exhibit 17 and when I look at the facial expression of Mr. Floyd, that does not appear in any way, shape, or form that that is light to moderate pressure.

Schleicher: So is it your belief then that this particular form of restraint, if that’s what we’ll call it, in fact violates departmental policy?

Chief Arradondo: I absolutely agree that violates our policy.

What is notable about Arradondo’s testimony (and Balko’s argument) is that it presumes that the departmental guidelines on neck restraints were relevant to Chauvin’s hold—which is a debatable proposition. However, if we are going to consider MPD policy on neck restraints to be relevant to Chauvin's hold, then it would be only fair to include all of the relevant information about neck restraints, not just the information that is unfavorable to Chauvin.

On balance, the section on neck restraints was favorable to the defense. This is because the MPD manual considered all neck restraints to be “non-deadly” uses of force. That applies not just to “conscious neck restraints,” which require the “light to moderate” pressure mentioned by Chief Arradondo in his testimony; it also applies to “unconscious neck restraints,” which involve enough force to render someone unconscious (i.e., more than moderate force).

All such restraints were taught as “non-deadly force,” which means, per the manual:

Force that does not have the reasonable likelihood of causing or creating a substantial risk of death or great bodily harm. This includes, but is not limited to, physically subduing, controlling, capturing, restraining or physically managing any person. It also includes the actual use of any less-lethal and non-lethal weapons.

One reason this would be relevant is that both the third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter charge required proving certain mental states beyond a reasonable doubt. The former required proving that Chauvin acted with “conscious indifference to loss of life” while performing an act that was “highly likely to cause death.” The latter required proving that Chauvin “consciously took a chance of causing death or great bodily harm.”

In both cases, the fact that the MPD taught that all neck restraints—including neck restraints that used more than moderate pressure—fell in the category of “force that does not have a reasonable likelihood of causing or creating a substantial risk of death or great bodily harm” would be highly relevant to the question of what Chauvin’s conscious mental state was. How do we know, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Chauvin was consciously aware of taking a life-threatening risk when the MPD specifically taught that neck restraints are unlikely to cause death or great bodily harm? Of course, this argument applies only if we consider the policy on neck restraints to be relevant. But you can’t have it both ways: either all of the training on neck restraints is relevant or none of it is.

During the trial, Chauvin’s lawyers wanted to show the jury an MRT training slide photo that looked fairly similar to Chauvin’s hold. But the prosecution moved to exclude the photo on the grounds that Chauvin was not trained on this particular slide. Judge Cahill agreed.

Balko agrees with the prosecution’s reasoning here. What’s more, he accuses me of getting my facts wrong. According to Balko, I’ve alleged that Chauvin was in fact trained on this slide.

However, what I actually wrote was that “this rationale does not survive scrutiny.” In other words, whether or not Chauvin saw this slide is irrelevant. The slide is important because it bears on the question of what was generally taught by the MPD.

The prosecution presented lots of evidence about generic MPD training, without the burden of showing that Chauvin specifically was taught each bit of training. In my view, the prosecution opened the door when Lieutenant Johnny Mercil, their key witness on MPD training, said that MPD officers were trained to “stay away from the neck” while performing MRT. Once that door was opened, the defense should have been allowed to introduce evidence to the contrary—including an MRT training slide showing an officer with his knee on someone’s neck, not as an example of improper technique, but as an example of proper technique.

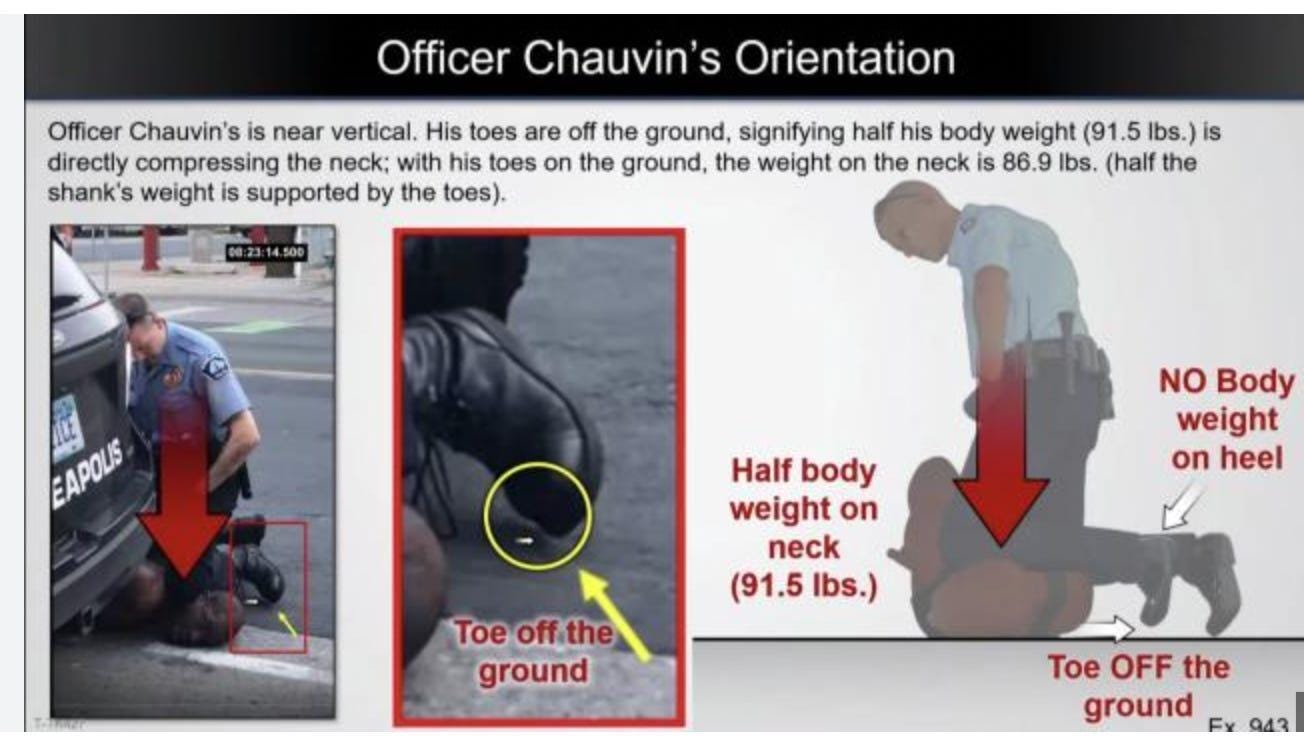

Now let’s move on to the question of how much weight or pressure Chauvin was in fact putting on Floyd’s back and neck. Balko argues that Chauvin’s hold differs from the MRT training slide photo because it looks like Chauvin has more weight on Floyd’s neck than the officer in the training slide. Look, for instance, at the different positionings of the toe and heel—and what that positioning suggests about how much weight is on the ground as opposed to on the person being held.

That is a reasonable observation. Still, Balko takes the point too far and in doing so reproduces one of the more dishonest tactics employed by the prosecution. In the trial, the prosecution showed a freeze-frame of Chauvin’s toe fully off the ground and argued that he therefore had fully half of his body weight on Floyd’s neck. They showed this graphic, which Balko reproduces. It reads “Officer Chauvin’s [sic] is near vertical. His toes are off the ground. . . ”:

What they do not tell you is that the moment when Chauvin’s toe is off the ground lasted mere milliseconds. You could literally blink and miss it. Try to find the same moment in the video.

Equally important is the fact that Chauvin didn’t raise his toe off the ground as an arbitrary increase in pressure—which is how it seems when presented as a photo. The video, however, reveals that Chauvin’s toe came off the ground in response to Floyd jerking his shoulder upward. To my eye, it looks like a counterbalancing pressure required to maintain Floyd’s body in place—a dynamic interplay between the upward pressure of Floyd’s shoulder and the downward pressure required to match it.

More important than what Balko distorts is what he omits entirely. Balko focuses on the training that is written in the MPD manual: you’re supposed to move the subject to the side-recovery position to avoid positional asphyxia, and you’re supposed to use a hobble—both of which Chauvin did not do. However, it is clear from the testimony at trial that what is written in the manual is only a small fraction of MPD training. And most of the MPD training that was favorable to the defense was not contained in the manual and is omitted from Balko’s analysis.

Lieutenant Johnny Mercil—the prosecution’s key witness on MPD training—testified that MPD officers were trained to believe that if a suspect can talk, then they can breathe. (They are also trained to be aware that people lie about medical emergencies to avoid arrest.) Officer Tou Thao, Chauvin’s partner, emphasized this bit of training in his interview with agents at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension:

Thao: [Floyd] was saying that he couldn’t breathe, but then he was obviously yelling and talking.

Agent: What does that mean?

Thao: Obviously, in school we’re trained like, “Hey, if a suspect is claiming that they can’t breathe, but if they’re talking, they’re breathing.” Because obviously, you have to be able to breathe in order to say something.

Mercil also testified that in some situations, an officer can hold a subject in the prone position (not turning them into the side-recovery position) until the scene is “Code 4” (meaning “the scene is safe”). He then testified that the reaction of bystanders could in theory warrant that action. Multiple witnesses, including Mercil, testified that MPD officers are trained to factor in all the aspects of a scene (including a hostile crowd) into their use-of-force decisions, not just the actions of the arrestee.

None of these aspects of training were in the MPD manual. Yet they are all relevant to Chauvin’s culpability—indeed, they are all aspects of training that were favorable to the defense. Balko, however, excludes these pieces of training from his analysis of Chauvin’s culpability.

Let’s start with the first piece of non-manual training: “if you can talk, then you can breathe.” We know they were trained on this idea, and we know that they were thinking of that mantra during the arrest, because both Thao and Chauvin say it at various points to assure the growing crowd that Floyd is okay. Indeed, Balko criticizes Chauvin’s use of this phrase—without mentioning that they were trained on it.

When asked about the “if you can talk, you can breathe” mantra, Dr. Tobin, the prosecution’s pulmonologist, replied: “It’s a true statement, but it gives you an enormous false sense of security. Certainly, at the moment that you are speaking, you are breathing. But it doesn’t tell you that you’re going to be breathing five seconds later.”

Tobin went on to explain that if someone is speaking, then you know two things: first that they must have inhaled just before speaking, and that their brain is “alert” and receiving oxygen while they are speaking. He explained that all of this, while true, leads to a false sense of security.

This is important for a few reasons. First, because if “if they’re talking, they’re breathing” is bad training, then that shifts blame from Chauvin’s choices to the MPD’s bad training—at least for the duration of Floyd’s speaking, which lasted for almost five minutes after he was put in the prone hold. For the duration of those nearly five minutes, a reasonable officer might have thought (based on their bad training): “Whatever I’m doing is compatible with him receiving enough oxygen, because he is talking continuously for minutes on end.”

The phrase false sense of security is notable here. Recall the states of mind required to prove the manslaughter and third-degree murder charges brought against Chauvin. They both required proving that Chauvin was consciously aware of huge risks but chose to take those risks anyway. If you have true-but-misleading training (“if you’re talking, then you’re breathing”) that gives officers a “false sense of security,” then it is not fanciful to imagine that Chauvin felt secure about what he was doing as a result of his training. “False sense of security” is quite a different mental state than “depraved mind”—which is the standard required for third-degree murder.

Is it possible that Chauvin was simply a sociopath and that’s the reason he felt no urgency to respond to Floyd’s “I can’t breathe” pleas? Of course. But there is another reasonable explanation.

Imagine that you’re a cop who has been trained with two ideas: people often lie about medical emergencies to avoid arrest, and no matter what they say (which again, may be a lie), if they’re talking, then they’re breathing. Now you encounter a suspect who won’t get in the back of a squad car because he’s “claustrophobic” (even though he was voluntarily sitting inside a closed car just minutes ago). He starts claiming that he can’t breathe before there is any weight on his back or neck. And once he is in the prone position, he continues to talk and yell for minutes on end—proof, according to your training, that he can in fact breathe. It is very easy to see how an officer trained in this way—and encountering Floyd’s specific situation—might ignore his “I can’t breathe” pleas not out of callousness but out of training.

Balko argues that “if you can talk, you can breathe” is an outright falsehood—not simply true-but-misleading, as Dr. Tobin argued. I won’t take a stance on that question here. But if Balko is right and it’s an outright falsehood, then that would shift even more blame from Chauvin and the other officers to the department that sent them into the field believing (and acting upon) a dangerous lie. The correct response in that situation would be to pay the family of the victim millions of dollars and aggressively overhaul the policy of the police department—not to throw the officers in prison.

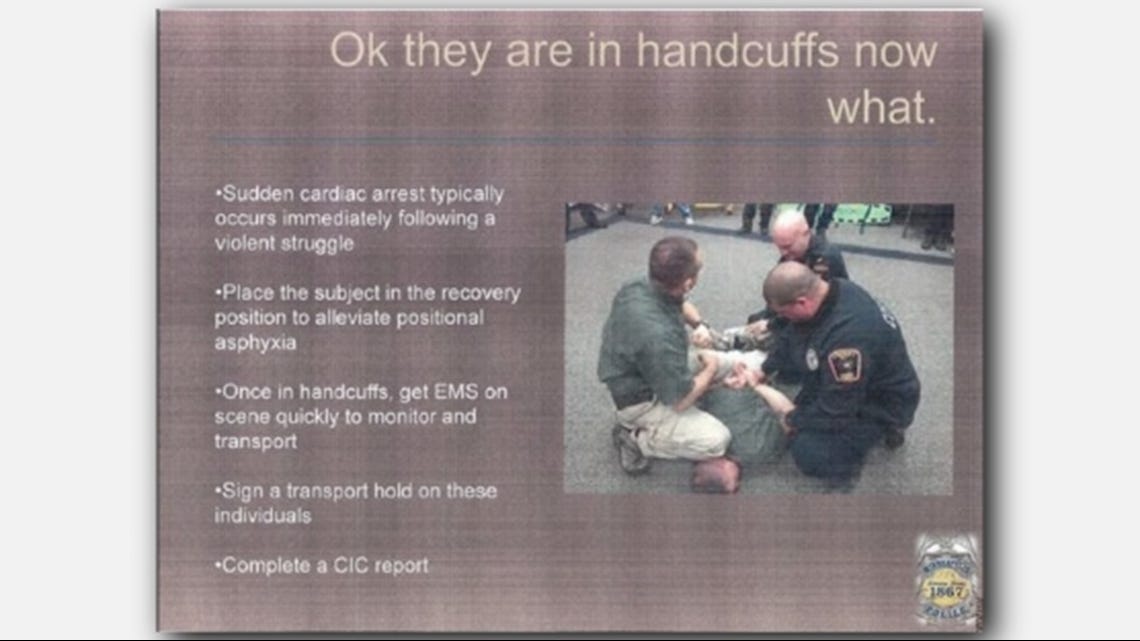

One of Balko’s arguments here is that MPD officers were warned about the dangers of positional asphyxia when holding subjects in the prone position. That appears to be true, based upon the MPD manual, the MRT training slide, and testimony at trial.

However, there are many important counterarguments to consider. Firstly, a report by the Minneapolis Department of Human Rights released in 2022 revealed that the MPD’s training was inadequate in just about every way imaginable. Many policies that existed on paper were not actually trained in practice. Even after Floyd’s death, they failed to train their updated policies:

MPD does not provide its officers with appropriate, timely, or adequate in-service training on important policies and policing practices. For instance, while MPD has updated its Use of Force Policy several times since an MPD officer murdered George Floyd in 2020, MPD failed to implement and train on the updated policy in a meaningful way. Instead, MPD provided officers with a 15-minute narrated PowerPoint presentation, highlighting some of the changes made to the Use of Force Policy in and around the fall of 2020. In some precincts, supervisors also provided officers with a high-level readout of the policy changes. MPD officers reported that for over a year after the new policy was in effect, MPD provided no substantive training to officers about the new policy, which prohibited neck restraints and chokeholds.

If that is how shoddy MPD’s training was post-Floyd, it’s easy to imagine how shoddy the training may have been before Floyd’s death led to increased scrutiny.

Further supporting the idea that many policies that existed on paper were not actually trained is Officer Lane’s BCA interview. When Lane was interviewed by BCA agents in July 2020, he mentioned that he knew about the side-recovery position not because of his MPD training but because of a previous job he had worked at a juvenile correctional facility:

Lane: Chauvin said, “We’re just going to hold them here until EMS arrives.” And I had suggested, with excited delirium, maybe we should roll him on his side just to. . . I think it’s something I had previously learned at a previous job where you roll him on the side to a recovery position or something like that.

Interviewer: Okay. What previous job would that have been?

Lane: I think it was JDC.

Interviewer: Did you work at a juvenile detention center?

Lane: Yup.

Lane’s answer suggests that he did not learn about the side-recovery position during his MPD training—though it was in the manual—leading one to question what else in the manual was not actually taught, or at least taught insufficiently. It’s not clear how consistent the training was, whether each officer was trained the same way, or whether every policy that existed on paper was trained in practice. What is clear is that there was a huge distance between what was written in the MPD manual and the sum total of what MPD officers were actually trained on. And by focusing narrowly on the former, Balko understates the strength of Chauvin’s defense.

Secondly, I would argue that in the specific case of Floyd, the training on positional asphyxia conflicted with the “if you can talk, then you can breathe” training in the following sense: the first urges caution while the second breeds complacency. An officer trained on both things might believe they are being cautious about positional asphyxia while simultaneously taking Floyd’s ability to talk as a sign that positional asphyxia clearly was not occurring in Floyd’s particular case.

The strongest counterargument here is to observe that Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck even after Floyd stopped talking. According to the prosecution’s key witness, Dr. Tobin, there were about 50 seconds between Floyd’s last words and the moment he died. And Chauvin continued to keep his knee on Floyd’s neck and upper back throughout those 50 seconds.

However, even here there is evidence on the other side to consider. First, from Lieutenant Johnny Mercil’s testimony, we know that MPD were trained that in certain situations, you can hold someone in the prone position with body weight (and not move them to the side-recovery position) “until the scene is Code 4.” Code 4 means, roughly, “everything is under control and the scene is safe.”

We also know from the testimony at trial that when the paramedics arrived at the scene, they did not believe that the scene was “Code 4” because of the hostile crowd—which is to say they did not think that it was safe for them to apply medical treatment. So they delayed treatment and did what is called a “load and go”—loading Floyd’s body into the ambulance and immediately moving to a safe location before applying treatment. If the paramedics did not consider the scene to be “Code 4” because of the hostile crowd, then it is not ridiculous to suspect that Chauvin had made the same judgment a few minutes earlier.

Just after Floyd loses consciousness—at 8:25:20 p.m.—bodycam video shows that Chauvin’s attention is drawn away from Floyd and to a hostile crowd member wearing a boxing hoodie who yells “I’m not scared of you, bro. You’re a fuckin’ pussy-ass dude, bro”—words that indicate a possible imminent attack. Chauvin responds “Don’t come over here! Don’t come over here!” (The moment is best viewed from both Thao’s and Lane’s bodycams.) Clearly, Chauvin and the other officers were worried about the crowd encroaching on the scene and potentially attacking them—minutes before the paramedics arrived. The scene was not Code 4 even then.

Finally, there is the argument that MRT requires the use of the hobble—a device that restrains a prone suspect by connecting their hands to their feet—which Chauvin did not use. But the reason why Chauvin did not use the hobble was both straightforward and defensible. Part of the tragic bad luck of the George Floyd arrest was that a freak miscommunication led EMS to arrive several minutes later than they typically would. Floyd was placed on the ground at 8:19 p.m. and EMS was called by 8:21 p.m. As one of the prosecution’s witnesses (herself a firefighter and EMT) explained, a normal EMS response time would have been three minutes or less—putting medics on the scene by 8:24 p.m., when Floyd was still breathing. The fact that EMS didn’t arrive until 8:27 p.m., she explained, was “totally abnormal.” In fact, it was so abnormal that she literally couldn’t believe it at the trial.

Without 20/20 hindsight, it was rational for Chauvin and the other officers to expect EMS to arrive by 8:24 p.m. or even sooner. The hobble takes around two minutes to put on and it is not the simplest process. Moreover, it has to be removed before medical treatment can be applied. So, at 8:20 p.m., when Thao retrieved the hobble, it would not have made sense for them to go through the difficult process of applying the hobble—which Floyd may very well have struggled against, requiring a further escalation of force to subdue him—when, best-case scenario, they’d just have to remove the hobble a minute or two after they got it on. As Thao explained in his BCA interview, that is why they chose to forgo the hobble after initially deciding to use it.

I would add that applying the hobble only to remove it moments later would arguably have delayed Floyd’s medical treatment. On those grounds alone, it was a reasonable decision at the time it was made. And it was within the bounds of MPD training—as they are not trained to robotically apply the small amount of their training that is included in the manual, but to make situationally appropriate decisions based on the totality of their training—most of which was not contained in the manual.

Conclusion

I think there was clearly reasonable doubt on whether Chauvin caused Floyd’s death. There were two rival theories of his death: the positional asphyxia theory (put forth by Dr. Tobin and endorsed by the prosecution), and the adrenaline surge theory (put forth by Dr. Baker and rejected by the prosecution). Both were reasonable theories, but only the former implicated Chauvin. That alone should have introduced reasonable doubt on all three charges.

As for whether Chauvin assaulted Floyd—that is, whether he used unlawful force outside the scope of MPD training—reasonable people can disagree on whether there was reasonable doubt. Balko would emphasize that MPD officers were trained to worry about positional asphyxia, move people to the side-recovery position as soon as possible, and use the hobble.

I would retort that they’re also trained to be aware that people lie about medical emergencies; they’re trained that if someone can talk, then they can breathe, and Floyd was talking for almost five minutes; they’re trained that in certain situations, you can hold someone in the prone position until the scene is Code 4 (and in this case, the scene was not Code 4); and putting on the hobble only to remove it moments later would not have been a wise choice at the time. I would also add that the sum total of training the officers received was probably inadequate, incomplete, contradictory, and may have omitted in practice many things that were “trained” on paper.

I agree with many of the classic critiques of the police as an institution. There is a culture of lying to protect their own, the “blue wall of silence,” and a certain kind of authoritarian personality who may be drawn to becoming a cop in the first place. There is pernicious racial profiling and needless disrespect. There is a sense of power and lack of accountability that can come with a badge.

All of it is true. Not of all cops, but many.

At the same time, policing is a more difficult and a less forgiving job than the rest of us have. We hand off situations to cops because those situations have become unmanageable—and then we ask the cops to manage them. They are given insufficient and sometimes contradictory training. They are expected to make quick judgment calls that are later judged in the harsh light of perfect hindsight—in situations where their own safety and sometimes their own lives are at risk.

The difference between one judgment call and another can be the difference between correctly doing your job and becoming a convicted murderer. This is a rather difficult knife’s edge to operate on. In some respects, the only similar profession is high-stakes surgery—though the surgeon’s safety is never at risk, and we are much more forgiving of surgical errors than we are of policing errors.

What’s more, none of the civil liberties concerns normally marshaled in defense of unpopular defendants has been on display for Chauvin. Consider this excerpt from the jury instructions: “During your deliberations, you must not let bias, prejudice, passion, sympathy, or public opinion influence your decision. You must not consider any consequences or penalties that might follow from your verdict.”

What are the odds that Chauvin received a trial in accordance with these instructions? Given the jurors who spoke about their fears for their physical safety, given the juror who was found wearing a “GET YOUR KNEE OFF OUR NECKS” t-shirt before the trial, given that everyone knew the city would burn if he was acquitted yet the trial location wasn’t changed, and given that the jury wasn’t sequestered in one of the most talked-about trials in modern American history—I would submit that the odds are close to zero.

Ultimately, we’ll never know how a jury might have weighed the evidence under even halfway normal conditions. And it is probably too late for any of this to matter for Chauvin himself. What is clear, however, is that there were many reasons to doubt that Chauvin was guilty of the crimes he was charged with, and the American public should not be afraid to say so.

Coleman Hughes is a columnist for The Free Press. Read his piece, “What Really Happened to George Floyd?” and follow him on X @coldxman.

To support The Free Press, become a subscriber today:

It is obvious to most people that have the ability to think for themselves that the thing was promoted by evil forces to create as much chaos as possible, and those police officers were sacrificial lambs.

Been meaning to do this for a while, and I'm finally doing it. POLICE KILLINGS IN MINNEAPOLIS BY YEAR:

2019 year with 14 killed:

* 5 were white

* 5 were black

In 2018 13 were killed

* 7 were white

* ONLY 1 WAS BLACK

I'm trying to find a pattern here like with George Floyd and I don't. 27% of people killed by police are black.

So now that the City Council plan to abolish the police won't come to a vote (they would have to change their City Charter), I went to finally look at who the police are killing, and you won't see the above stats in the news because the narrative doesn't care about facts. Last year had a whopping 14 killings by police, which is more than NYC or Chicago had (Chicago's remarkably low, so that's another story). Only 4 killed by police this year (3 white, 1 was George Floyd).

CRIMINAL CONTEXT (also omitted by media): Minneapolis is 18% black and 64% white, but black folks make up around 75% of violent crime suspects and 57% of murder suspects.

And supposedly this is a uniquely anti-black police force? In every city I've looked at from Baltimore to NYC to Chicago to San Francisco I have not found any evidence that police are treating black citizens dramatically different when it comes to force. You're essentially being lied to by the media, activists, politicians, and pretty much everyone. These are lies of omission.