KIBBUTZ HANITA, Israel — In the late 1930s, when the land that is now Israel was under British rule, a young intelligence officer named Anthony Simonds spent time in Galilee, in remote hills that would eventually become the Israel-Lebanon border. He recorded memories of his time there in a colorful but unpublished memoir now kept in the Imperial War Museum in London. Rereading the officer’s recollections now, a year into the war that has devastated northern Israel and southern Lebanon, is an eerie exercise—a reminder of what Jews created in Israel, then lost last fall, and are now fighting to reclaim.

As I write these lines, Israeli infantrymen are pushing into Lebanon to clear Hezbollah guerrillas from the vicinity of the border while the air force, in strikes throughout southern Lebanon and in Hezbollah’s stronghold in the southern districts of Beirut, is methodically killing the group’s commanders and destroying the vast arsenal supplied by Iran. A direct Israeli strike against HezboIlah’s patron, the Islamic theocracy in Iran, seems imminent.

None of this would have made sense to Simonds of the Royal Berkshires: When he was a young man in uniform more than 80 years ago, Iran was a distant monarchy ruled by the shah, and there was no Hezbollah and no state of Israel. Lebanon was ruled by France.

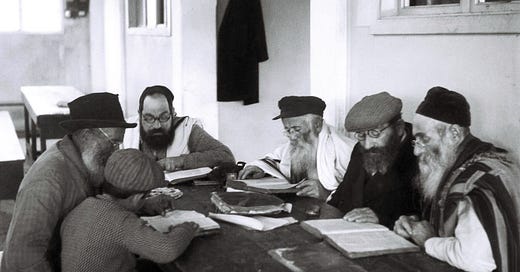

“I have driven my car on rough tracks, sometimes in the Lebanon and sometimes in Palestine,” wrote Simonds. On one page of his typewritten memoir he recalls coming across a new frontier outpost. This kibbutz had been established one night in March 1938, and was inhabited by about 100 young Jews, many of them refugees from Europe, who had erected a wooden tower and stockade in a matter of hours on a plot purchased from Arab landowners by the Zionist movement. After their arrival, the pioneers faced an attack in which two of them were killed by Arab guerrillas. As they dug in and farmed in subsequent months, becoming symbols of Zionist pioneering, eight more of them fell.

The place left a deep impression on Simonds. The little community, he recorded, was meant to mark the future border of the Jewish national home, provide early warning of guerrilla attacks, and serve as a way station for Jewish refugees arriving on foot from the north. “I have stayed there,” he wrote, “and it was an eye-opener to me to see the armed sentries patrolling the boundary fences of the settlement, of whom nearly 50 percent were pretty young girls of 15 years to 16 years of age!”

The pioneers named the kibbutz for an ancient Jewish village that once existed in these same hills: Hanita.

When the state of Israel was founded 10 years later, in 1948, Hanita was one of the points that set the northern frontier, which sat a stone’s throw from the pioneers’ homes.

Today, on the steep road that leads from the lowlands of Western Galilee up to the hilly country along the border, there’s a re-creation of the wooden tower from the heroic night of Hanita’s founding 86 years ago. A sign by the tower informs visitors that the first pioneers in 1938 “stayed at Hanita and despite the Arab attacks, which began that first night and recurred frequently after that, the community held fast.”

When I visited three weeks ago and climbed the ladder to the top, the Mediterranean was visible to the west. Just to the north were the slopes burned by Hezbollah rockets and debris from Israeli interceptors.

Today, Hanita is abandoned. A year ago, on the morning of October 7, 2023, there were 700 residents. But then Hezbollah opened fire on northern Israel in support of the Hamas offensive out of Gaza, marking the beginning of the multifront war against Israel by the Iranian proxy alliance. When I arrived, the only people here were members of a security team: two men guarding the gate, a few on patrol, and a few others drinking coffee in a kibbutz building now fortified with vertical concrete slabs. The kindergarten sat empty by a mangled swing set and a playground blackened by the impact of suicide drones.

The same scenes repeat along the entire length of the Israel-Lebanon border.