Michael Shellenberger has no idea when life begins. Nor do any of the other wannabe governors on stage in Rancho Mirage, two hours east of Los Angeles. But that doesn’t stop them from blurting out “Conception!” like a sanctimonious flugelhorn when the moderator asks. Shellenberger can’t bring himself to do that. He’s at a loss.

The radical-turned-Democrat-turned-independent is too measured—too liberal—to give the Republican crowd the sirloin it craves.

My God, the crowd: three-hundred souls, give or take, squeezed into this ballroom at the back of a flashing, neon hotel-casino extravaganza on the edge of the desert, eating rubbery chicken breasts stuffed with a yellowish cheese. They’re weathered, wrinkly, suntanned, and they wear ill-fitting blazers and ties and pleated pants. There are a few low-cut dresses, fading tattoos that droop just a bit around the ankles and wrists, and the occasional American-flag bandana stretched tight around a scraggly, Jesse Ventura visage.

They’re angry. They’re angry about crime and critical race theory and inflation and the death tax. But most of all they are angry about being left behind, and even though this is supposed to be a GOP-sponsored forum where candidates share ideas about how to make California livable again, it’s really all about candidates venting the rage that the crowd so obviously feels.

“I would not presume to know the mind of the good Lord,” Shellenberger says at last. It sounds forced. It is. He’s not used to droning on about his relationship with Jesus. The thing is, he has one. He tells me that the next day. He also admits he didn’t expect the abortion question—the forum comes just one week after the Alito leak—which is kind of unbelievable.

Then again, so is Michael Shellenberger’s whole campaign.

This is a man who, as a high school senior in 1988, ventured to Nicaragua to study Spanish with the Sandinistas, then immersed himself in Noam Chomsky, learned Portuguese, went to Brazil, hung out with Rio’s radical elite, worked for some enviro-anarchists in San Francisco, saved redwoods, became a Time Magazine Hero of the Environment, advised MIT’s Future of Nuclear Energy Task Force, and co-founded an institute that tries to tackle climate change. No one on stage or in the crowd brings any of that up.

It could be because they have no idea who Shellenberger is: He jumped in the race in March, and he’s only raised a little north of $700,000. But it could be because everyone gets that that old game is over and that Shellenberger is a new kind of candidate.

That’s why he was on Joe Rogan. And Tucker Carlson. That’s why The Wall Street Journal weighed in on the race. That’s why he’s here. Because the world is upside-down, the state needs a dark horse to save it, and a lot of very smart people think that Michael Shellenberger might be the person to pull it off.

Here’s how: In California, they have open primaries. The top two vote-getters move on to the general election. That could be two Democrats, two Republicans (not going to happen in this lifetime), a Democrat and a Republican, or a Democrat—in this case, Governor Gavin Newsom—and an N.P.P., as in no party preference, which would be Shellenberger.

Usually, there would be a few career Republicans in the field, and one of them would come in second, and this person would face off against Newsom and get destroyed in November. (If Republicans got lucky, they’d break 40 percent. They haven’t won statewide since 2006.)

But last year, Republicans tried to recall Newsom and got clobbered, with the Democratic governor capturing nearly 62 percent of the vote. So this year, any Republican with money or name identification is staying away. The field is wide open.

That’s not because voters love Newsom. Sure, he has the whole Camelot of the West vibe, but the state’s an absolute mess. Pick your issue: the homelessness crisis (as of early 2020, there were an estimated 161,000 homeless people in the state), or the lack of affordable housing, or the broken schools, or the crumbling energy grid, or the fires, or the drought, or the fentanyl crisis. Then there’s the twin exodus: Silicon Valley’s best to Miami and Austin and the state’s middle-class families to Arizona and Nevada.

And this is to say nothing of the French Laundry brouhaha, in which the pro-lockdown, pro-mask governor was spotted maskless in November 2020. Or his infamous banned-books Twitter post, which featured a photo of the governor reading books banned in other states, including “To Kill a Mockingbird”—which had also been banned in California. Under Newsom.

Enter Shellenberger.

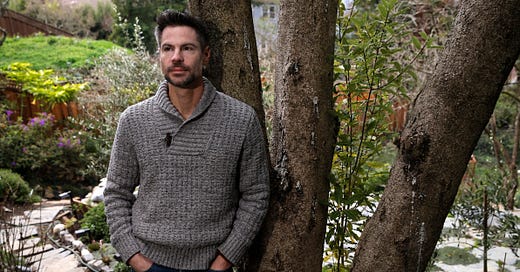

The boyish 50-year-old does not look anything like a politician, what with the narrow runner’s frame, the navigator glasses, the soothing demeanor. At the candidates forum, he wore a navy Prada knockoff jacket—a Spada—and handmade Italian loafers. He looked like your favorite professor of comparative literature, not a politician. (Once, several years ago, I had lunch in the Senate dining room with Trent Lott, the then-junior senator from Mississippi, who recalled an older, wiser Southern pol telling him decades before, “If you can’t take their money, drink their whiskey and sleep with their women, you don’t belong in this game.” By that standard Shellenberger is DOA.)

“Helen’s fear was, ‘You can’t be inauthentic, and therefore, you can’t be a politician,’” Shellenberger told me. He was referring to his wife, Helen Lee, a sociologist who works at a nonprofit in Oakland.

It was the day after the GOP powwow, and Shellenberger and I were tearing through the Inland Empire, that beige, undulating patchwork of strip mall-subdivision ennui, on our way to the beautiful people: Shellenberger was set to meet with a real-estate developer (and possible donor) for lunch at the steakhouse Baltaire. Helen had watched her husband run in 2018 for governor. He ran as a Democrat. He came in ninth. Better to write books. Shellenberger’s 2020 book, “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All,” had been a bestseller. His follow up, “San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities,” had generated a ton of buzz. He had built a great career advocating for nuclear energy and fighting the state’s ineffective homeless policies. His essays (perhaps you remember this one he wrote for us) and his videos regularly go viral. So why run again?

When I asked him, he said: “My feeling was, if there’s ever a moment that somebody could run in an authentic way, it would be now. Because I think it’s not a normal time.”

Sure, but that misses something fundamental about Shellenberger: the combination of his relentless, almost manic energy and his willingness to go head to head with his own tribe. What he lacks in savvy, he makes up for with an almost iron stomach for conflict.

That became clear during his days as an environmental activist. He’d spent years fighting for renewable energy, but there were limits to what renewables could do, and, starting in the mid-aughts, he started to rethink the conventional wisdom on nuclear-power plants. Most environmentalists hated them. He didn’t get it. Nuclear was an abundant and sustainable energy source, and there were new technologies that made it safer, reduced radioactive waste, and enabled growth. Wasn’t that good? The environmentalists didn’t think so. They accused him of being a traitor. “It was always the usual Judas sellout caricature,” Shellenberger said.

He had the same experience with homelessness, although Shellenberger pointed out that, “by the time I got to ‘San Fransicko,’ I knew there was a double-game being played.” In other words, he knew there was a chasm between what progressive activists said they wanted and what they actually wanted. They claimed to want to end homelessness, just as the environmentalists had claimed to want to combat climate change. But that wasn’t true. Really, they wanted the fight, the feeling of moral superiority and, of course, the cash for their NGOs.

In both cases, he’d started from a progressive place—the environment is precious; so are human beings sleeping in tents—and wound up somewhere else. It was not exactly conservative, but it had a conservative hue to it. (“There needs to be some renewal of faith in civilization, in liberal democracy, in, for lack of a better word, in capitalism,” Shellenberger said in the car.)

He called his worldview “physicalist,” as in: How does this transform the physical, or lived, environment, in the center of San Francisco or the Central Valley or the Mojave or wherever? Another way of describing it is commonsensical. He wanted to fund the police to clean up bad neighborhoods, and he wanted to incentivize development, and he wanted a “tax peace.” In a text, he explained: “No increase or decrease until we end homelessness crisis, achieve school choice, and energy/water/housing abundance.”

There was something very American about it. Yeah yeah yeah, ideas are fine, but what do they actually do? How do they make life better for people right now? William James—the great Harvard philosopher, the father of pragmatism—had spent his life thinking about this.

“Nine times out of ten the concrete solution doesn’t fit the preexisting dogmas,” Shellenberger told me. The challenge was getting other people—voters—to extricate themselves from the platitudes and labels.

We had decamped to the man cave in the Berkeley Hills house he shared with Helen. To get to the man cave, you followed a stone path down to the back of the house, up a short flight of stairs, into an airy cocoon with the view of the bay, the kitchenette, the mini-library. The feng shui was perfect. We ordered Indian, and Shellenberger served white wine. He didn’t drink. He hasn’t since 2018, when his kids told him he had a problem, and he went cold turkey. (His kids, ages 23 and 16, live up the street with their mother, Shellenberger’s first wife.)

We were talking about why it felt like everything was falling apart. “I think one of those under-discussed things is the way secularization, anxiety about death that comes with secularization, is driving a lot of these contemporary neuroses—the hyper-wokeness, this kind of mania—and you go, ‘What is the secular religious alternative?’ And it’s patriotism,” he said. “It’s something around love of country, love of California, some love of place, and some sense of responsibility for it. You don’t want to take responsibility for things you don’t care about.”

The tech people should have been eating this stuff up. They were all about finding solutions to problems, and Shellenberger’s campaign was like a gorgeous slam-dunk pitch deck replete with charts and stats and striking visuals. And his style, his grit—what did they always say, something about investing not in the startup but the founder? And what about his team? He had Rob Stutzman, one of the engineers of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s successful 2003 defeat of Governor Gray Davis; David Kochel, who had helped Mitt Romney secure the 2012 GOP presidential nomination; and Luke Thompson, who ran the super-PAC that had helped put J.D. Vance over the top in the Republican primary in Ohio and was now running the super-PAC backing Shellenberger.

But the serial entrepreneurs, the venture capitalists—they’d been reticent. There’d been a little financial support: Matt Mullenweg, the founder of WordPress, and Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI and former president of Y Combinator, had each maxxed out, giving $32,400 apiece. A handful of engineers and developers had each contributed a few hundred bucks. That was it.

Over the weekend, Shellenberger seemed to be picking up steam. The venture capitalist David Sacks tweeted his support for Shellenberger. Three hours later, the journalist and podcaster Peter McCormack did the same. (Sacks has contributed $150,000 to the pro-Shellenberger super-PAC, which plans to target the L.A. market.) The big question marks inside the campaign were Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. And what about Chamath Palihapitiya, the former Facebook executive who had supported the recall? And Brian Armstrong, the CEO of Coinbase? Shellenberger was the kind of disruptor you’d think they’d embrace.

Some of the tech people, especially the younger ones, weren’t buying it. They thought his vision was too pat, too limited. “His platform is just fenty,” a V.C. in her late thirties texted. She meant fentanyl. Others were hedging. They liked Shellenberger, but they wondered whether he had the ruthlessness to execute. They wanted to see how the primary would go.

The primary is June 7. Shellenberger’s team says they need 12 percent of the vote to come in second. There are 26 candidates in the primary, including Newsom and Shellenberger, meaning Shellenberger has to beat 24 people. Shellenberger said they weren’t polling, so they were kind of flying blind. But he was confident. He could feel it. “It’s everywhere,” he said. “Something’s happening.” Shellenberger said that his ex-wife, “with whom I’ve had a chilly post-marriage relationship, called to say that she’s voting for me. She’s anti-nuclear and dislikes my pushback on environmentalism. ‘On homelessness, I really agree with you,’ she said. It was a nice, tender surprise.”

In late April, a few weeks before I met up with him in Rancho Mirage, Shellenberger had given me a walking tour of the Tenderloin, the epicenter of San Francisco’s homelessness calamity, and it was grotesque: human beings on sidewalks sticking needles in their ankles and asses, smoking crack, defecating, breast feeding, buying drugs, selling them. The cops in plain sight of the dealers with their hoodies and backpacks. Most of the dealers chit chatting with each other on corners across the street from playgrounds. Zombies wandering in and out of the century-old hotels overflowing with rats and needles and pipes.

It was obvious that the left-right assumptions—Love is all you need! Put ‘em on a bus to Reno!—were inadequate. What was needed, Shellenberger said, was “the three P’s”—policing, psychiatry, probation. His big idea was Cal-Psych, universal mental-health coverage. Maybe. What was most striking was watching him shaking hands with homeless mothers and addicts and bike thiefs. He had been here before. He knew the terrain. He called himself “technocratic”: There was a massive problem in the middle of this city he loved, and he wanted to do something about it, and that would require someone who approached things differently. Not like a politician, who told the people what they wanted to hear but never looked at the misery in front of them and said: “This is not how human beings are supposed to live.”

He recalled being seven, and his parents getting divorced, and then, a few months later—it was April 1980—riding his sister’s lame, banana-seat Schwinn to soccer practice and getting slammed by a 17-year-old in a truck and bleeding from both ears and almost dying. It was a lesson. It wasn’t just that death was a part of life. It was, he said, that “death is near, not far.” That just beneath the surface of the everyday, there was the constant threat of losing everything. The flip side of that, of course, was a heightened sense of urgency. He always felt like he was trying to catch up with his shadow. “At the same time,” he said, “it feels like the moment has caught up to me.” The question is whether he can harness all that energy and navigate his way through the many political minefields all the way to victory. He was still a little sore about the night in Rancho Mirage.

“When the soul enters the body, when life begins—I don’t have certainty on that,” he said. “And yet, you look around society, people seem to have a lot of certainty about that, and then total confusion as to how to deal with people with psychosis. They’ve got it completely upside down.” It boggled his mind that the other candidates running for governor were 100-percent certain about what they couldn’t know, and weirdly unsure about how to fix things that could be fixed.

“Politics should be a means to an end of a good society,” Shellenberger said. “They’re making it the end.” He was referring to the homeless activists who were his nemesis, but he could have been talking about the environmentalists or the pro-lifers in the desert. “Their real goal is control and moralizing and power. Mine is freedom, care, civilization.”

I hope Shellenberger wins. I suspect he is California's last hope.

He sums up the overall problem--not just with California politicians, but with political leaders all over the U.S--very astutely: "100-percent certain about what they couldn’t know, and weirdly unsure about how to fix things that could be fixed."

What could be the downside to electing anyone besides Newsom? How could anyone do worse? I listened to Shellenberger's interview with Rogan. I'm what many on the left would now call a red-pilled right-wing conspiracy theorist (i.e. I don't mindlessly accept everything the mainstream media preaches about Covid and find myself increasingly disenchanted with the Dem party) and I found his interview refreshing. Finally, like it used to be all of ten years ago, here was a liberal politician who I disagreed with on many of his suggested policies but who I found I can respect and, if elected, find many areas of agreement with.