The Free Press

Last week, I sat in synagogue on Rosh Hashanah and listened as a congregant stood in front of the crowd to deliver a few words of wisdom called a Dvar Torah. The congregation, like so many others around the world that day, was quiet and eager, desperate to hear something hopeful and sensemaking after a year of tragedy and disbelief.

“We live at a time,” he declared, “when the decision to bring new Jewish children into the world is an act of courage.” I looked down at my 2-year-old on the floor, snacking on a granola bar and rolling a blue toy car over my feet. He went on: “Jewish parents knowingly put their sons and daughters at risk simply by bearing children and binding them to Judaism and the Jewish people.” I looked down at my big belly, now almost five-months round.

The words stung. Our most primal instinct as parents is to guard and protect our children. We smother their scrapes with kisses and “magic dust,” as one of my kids likes to call the imaginary sprinkles I put on his boo-boos. We say, “Be careful” as they jump on the couch with glee, not because we want to be a nag, but because a fall—any fall at all, even a minor bump—hurts us much more than it could ever hurt them.

But the words also resonated in another way. As the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, I have often thought about the weight of what it means to bring Jewish children into the world.

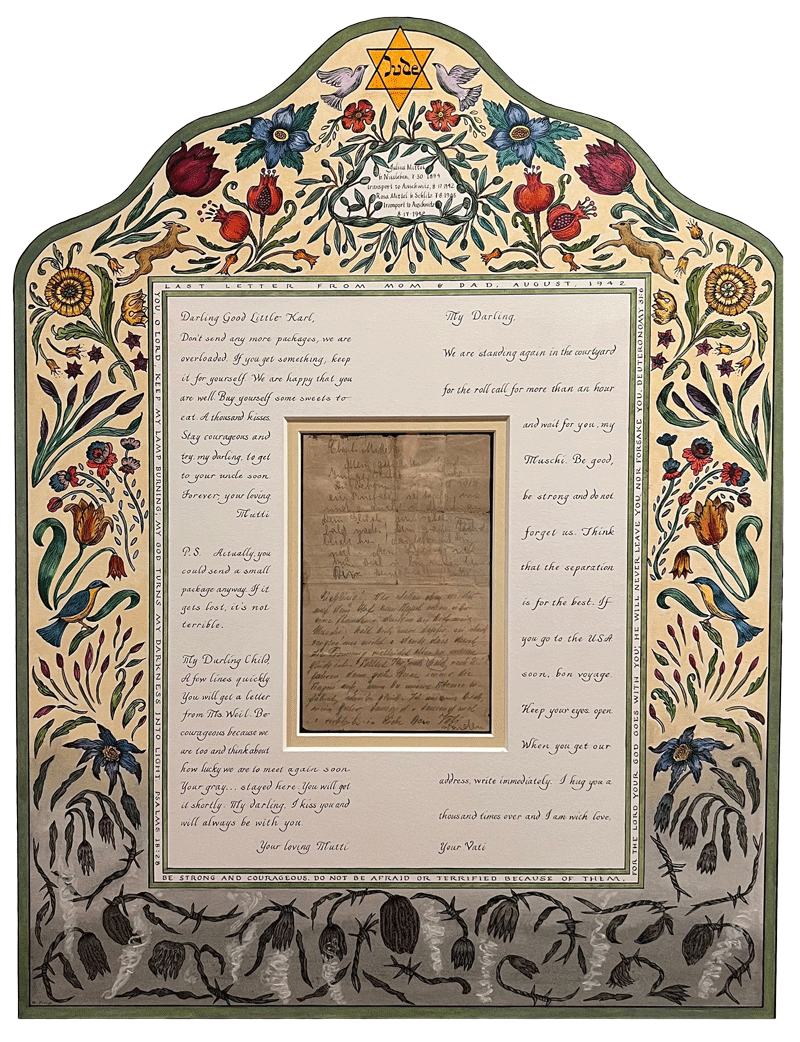

In my parents’ house, right past the kitchen on the hallway to the left, hangs an old, framed letter. It’s a letter—the last one—written to my grandfather, from his mother and father after they made the painful decision to separate from their son in August of 1942. My great-grandparents, Rosa and Julius, had been sent to an internment camp, Camp des Milles in France, and—in a desperate attempt to save their only son’s life—they sent my grandfather Karl, who was just 13 years old, to hide with an aunt and uncle in Vichy France, which they thought would be safe from the Nazis. Here is the translation from German and Yiddish:

My beloved child,

A few lines quickly. You will receive a letter from Ms. Weil. Before that, be good as we are concerned about your happiness. We will meet again. Your grey…[smudged writing]...stayed here. You will get it. My beloved, I kiss you, and I will always be with you.

Your dear mommy

My darling,

We are standing again in the courtyard for roll call for one hour, and we think about you, my Muschi. Be good, be strong, and don’t forget us, and think that through separation comes perhaps our happiness. If you go to the USA, then have a nice trip, keep your eyes open. When you know our address, write immediately. I embrace you my Goody a thousand and thousand of times, and remain in love.

Your daddy

Weeks later, they were both deported to Auschwitz in Poland, where they were murdered.

Growing up, the letter on the wall was a constant reminder not just of our family’s personal suffering and sacrifice, but also of the fragility—and ultimately, resilience—of life as a Jew in the world.

But it was also a relic of the past. After all, the letter is old and yellowing, the cursive handwriting is starting to fade, and the edges of the paper are beginning to rip. Mounted on the wall for every guest passing through our house to see, it is an indication of how far we’ve come since the days of the depths of evil.

And then October 7 happened. And Jewish mothers and fathers were, once again, making the ultimate sacrifice. Parents like Hadar and Itay Berdichevsky, who were butchered in their home in Kibbutz Kfar Aza, but managed to save their 10-month-old twins, who were found crying in the safe room 14 hours after the massacre. Parents like Smadar and Roee Edan, who were also murdered in their Kfar Aza home. The father, Roee, was shot shielding his 3-year-old daughter with his body. He was killed. She survived.

While my first two kids, a 2-year-old son and a 5-year-old daughter, were born with a sense that history was behind us, my third will be born in the post-October 7 era, a time in which our holiday from history is over.

And that’s part of the reason we decided to have her.

Not because I’m courageous—I don’t think I am. Certainly not in comparison to the brave men and women I spoke to and met over the last year in Israel—real heroes who ran towards the fire when confronted with the worst disaster imaginable. These are people who looked into the abyss without fear, and emerged with a level of civic obligation, duty, and sacrifice that is unrecognizable to most Americans today.

Rather, I think of my decision to bring a new Jewish child into the world as an act of necessity. The global Jewish population, as of today, hasn’t even reached pre-World War II numbers. In 1939, the global population of the Jewish people had peaked at around 16.6 million. Today, our ranks add up to just 15.7 million worldwide.

My family alone, when you tally up the dead from both sides of our tree, lost at least 10 people (that we know of) because of Jewish persecution—be it the pogroms of the late 1800s, World War I, or the Holocaust. Having another child and binding her to Judaism and the Jewish people is my duty to them. They gave their lives so that we could live.

And although I wish it weren’t still possible, so did the 1,200 Jews who were killed on October 7, 2023, and hundreds more over the last year of war.

Late in the summer of 1942, my grandfather’s aunt sent him to a makeshift orphanage in France called Château Montintin. (The non-Jew who worked at the chateau was later awarded with a Righteous Person designation.)

When the Germans found out that the orphanage was hiding Jewish kids, the Gestapo came to take different groups of kids on “picnics.” The children never returned. The Gestapo first asked for the oldest kids. A few days later, they returned asking for the next oldest group. My grandfather, who was then 14 years old, was one of the oldest, so he realized that he would soon be asked to go. Before they were able to invite him on one of these picnics, the French Resistance came to the orphanage and asked which of the Jewish kids had relatives in Switzerland. My grandfather said he did, even though he did not, because he knew it might be his only way to survive.

He left that night with a group of Jewish kids on a three-day trip to the border of Switzerland. When he arrived, his legs were diced up from barbed wire, and he had a fever so high he was admitted to the hospital.

Beyond the lacerations on his legs or the bacteria streaming through his blood, the scar I think about most now that I am a mother myself is the one that no one could see: This child was now an orphan.

At the age of 17, my grandfather left the orphanage in Ascona, Switzerland, where he lived for three years, and immigrated to the U.S., where he became known as “Charlie” and stayed with his uncle in New York City. A few years later, he met Jane, the woman who would become his wife, in the Bronx apartment building where they both lived. Unbelievably, they were from the same city in central Germany—Erfurt—which she had also fled during the Holocaust.

In 1955, Jane and Charlie had my father, who they named Michael. Sadly, my grandfather died a little more than 30 years later, before I was born. But I have the letters.

“Be good, be strong, and don’t forget us,” his dad had asked him in his final note.

We won’t. The new life growing inside of me is my promise.

Candace Mittel Kahn is the executive producer of “Honestly” and “Raising Parents” at The Free Press.

To support more of our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

They say every American remember where he was and what he was doing when he learnt about 9/11. I am french, but I do too (I was 12 years old at the time).

Yet, I also remember exactly what I was doing when I learnt about October 7th.

It was the middle of the night, and I was I my bed, nursing my two months old baby. She was still very slow to drink then, and to pass time, I used to read news on my phone or books on my Kindle.

And so, browsing CNN.com, I learned about the horror of what was still unfolding in Israel. And it the following days it got worse, as I learned about the rapes, the kids butchered in front of parents and vice versa.

Yesterday I started reading Bari's article about the 1 year anniversary.

And I stopped as soon as I saw the photo of the mother terrified with her two kids in her arms.

Having your children killed or taken from you is the worst nightmare every parent has, and I just can't confront it.

Somehow, the terror of this mother is mine, and I just can't face it. I can't even read about it without fearing for my own children (I am not a Jew, if you wonder).

How some people can support Hamas / Hezbollah / Iran and hate the Jews is beyond me.

Congratulations to the author for having another baby, I wish you the best ❤️.

It was very powerful. Thank you. Bless you and your family.