The Free Press

On March 29, 2023, a 31-year-old American named Evan Gershkovich was meeting a source at a steakhouse in the city of Yekaterinburg, east of the Ural Mountains. The Wall Street Journal reporter had planned to return to his apartment in Moscow, but he never got there: he was picked up by the FSB and dragged out of the restaurant with his shirt pulled over his head. Then, a few months later, the American son of Soviet émigrés was sentenced to 16 years in a penal colony on sham charges of espionage.

Today—491 days since his arrest—he is on a plane back to freedom.

His release was part of what the Journal called the “largest East-West prisoner swap since the Cold War.” (You can read about the secret negotiations that led to the exchange in the WSJ.)

On one side of the swap: terrorists, killers, and spies, including, most infamously, Vadim Krasikov, a convicted Russian assassin who was serving a life sentence in Germany for murdering a Chechen fighter in a Berlin park in 2019. There are eight such villains worthy of a Homeland episode currently en route to Russia.

On the other side: journalists, dissidents, and democratic activists. There are sixteen of them. They include heroic political prisoners like:

Oleg Orlov: a prisoner of conscience who is the co-chair of Memorial, the human rights organization that was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022.

Alexandra Skochilenko: a 33-year-old Russian artist, musician, and anti-war activist who was arrested and charged with “knowingly spreading false information about the Russian army” after she replaced five price tags in a local supermarket with stickers containing information about Russia’s war against Ukraine. (“How fragile must the prosecutor’s belief in our state and society be, if he thinks that our statehood and public safety can be brought down by five small pieces of paper,” she said during her sentencing in 2023. “Despite being behind bars, I am freer than you.”)

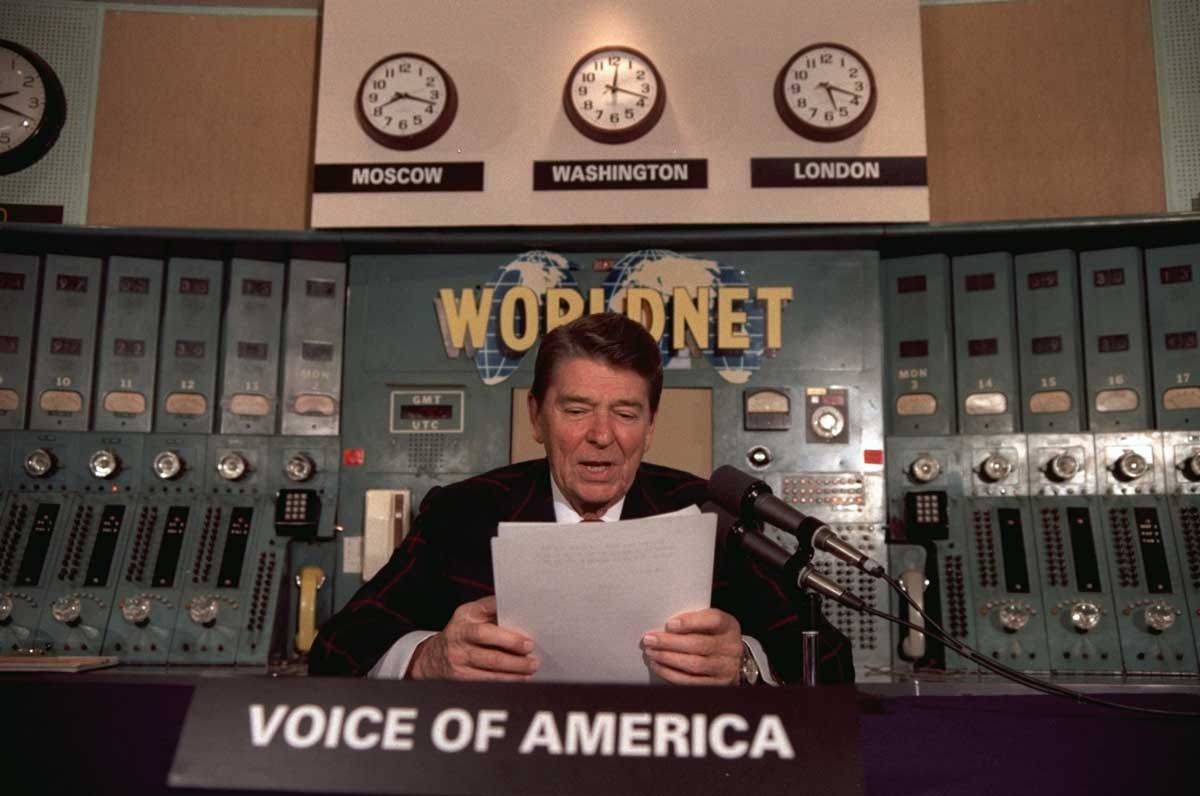

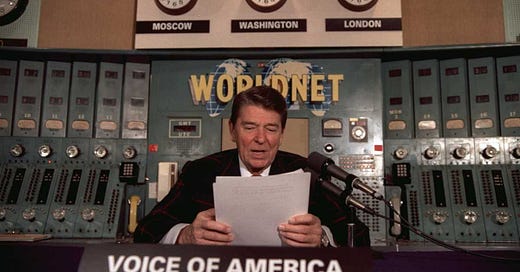

Alsu Kurmasheva: the Prague-based editor for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, who was detained last year in Russia while visiting her sick mother. Kurmasheva is also an American citizen and a mother of two.

Paul Whelan: a former Marine turned corporate security executive who was arrested in 2018 and accused of being a spy. He, like Gershkovich, was sentenced to 16 years of hard labor.

Vladimir Kara-Murza: an opposition leader and journalist who survived two poisonings. Kara-Murza won a Pulitzer for his columns written from jail. Last year, when he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for publicly criticizing Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine (the conviction was for “treason”), he gave a speech before the court that we proudly published in The Free Press.

“I also know that the day will come when the darkness over our country will evaporate,” he said. “When black will be called black and white will be called white; when it will be officially recognized that two times two is still four; when a war will be called a war, and a usurper a usurper; and when those who fostered and unleashed this war will be recognized as criminals, rather than those who tried to stop it.”

The person who tried harder than anyone to stop it was a man who did not live to see his liberation today: Alexei Navalny, who died on February 16 in a penal colony in the Russian Arctic. Three of those released today—Lilia Chanysheva, Ilya Yashin, and Vadim Ostanin—were close allies of the opposition leader, whose historic letters from his Siberian gulag were published in these pages.

Navalny, one of the great heroes of the twenty-first century, wrote those letters to Natan Sharansky, one of the great heroes of the twentieth century. When I heard news of the prisoner swap I called Sharansky, who spent nine years in the gulag and whose memoir, Fear No Evil, inspired Navalny.

“Avital and I are very excited and emotional,” he said, referring to his wife, who fought tirelessly for his release. “It was not even clear whether some of these prisoners would physically survive—whether they would be able to build a family. It is a very emotional moment of reunification and renewed hope. We identify so strongly with these families.”

“When I was in prison I was very optimistic. Not about myself, but about our struggle and our ultimate victory over that evil system. But about yourself, you can never be sure. And you try not to live with this dangerous hope because if you are only in hope, you can be broken very easily,” he said. “Navalny was very optimistic about the future, but he was sober about himself. When you are in this situation, you cannot think about your release but you can think about the ultimate victory—the defeat of evil.”

But what if defeating evil looks like giving in to it? Ben Domenech, writing in The Spectator, notes the terrible incentives inherent in the prisoner exchange, despite his close personal relationship with Kara-Murza: “Until the day that the United States brings real pain to these kidnappers, without giving them a bit of satisfaction, the abduction and jailing of Americans around the world will continue, and get worse, and grow,” he wrote.

“An American president should never be willing to submit to this type of extortion. Our willingness to shame ourselves is now baked in. The country needs a president with the strength to say no, and to hit back—and who understands that once you pay the Danegeld, you never get rid of the Dane,” he continued, quoting Rudyard Kipling.

Sharansky knows this only too well. He lives in a country—Israel—that in 2011 exchanged more than 1,000 prisoners for a single captured Israeli soldier, Gilad Shalit. Among those released was a Palestinian terrorist named Yahya Sinwar. Sinwar would go on to orchestrate the massacre of October 7, 2023. Along with the more than 1,200 innocent people slaughtered and the more than 250 stolen into captivity that day were American citizens, including five who remain alive: Edan Alexander, Omer Neutra, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, Sagui Dekel-Chen, and Keith Siegel. They have been held by Hamas for 300 days.

“Many people are bewildered, saying we are releasing murderers and spies and they are being exchanged for innocent or even noble people. And that’s unequal. More than that, the Russians are going to be motivated to kidnap more. It’s all true,” Sharansky said of today’s deal.

“On the other hand, I want people to understand whenever you are taking one more democratic dissident out of the claws of this beast it is a big victory. It shows that there is hope and they cannot fully control those who are challenging them. The KGB tells you you won’t get out alive. This is proof that they are wrong, and that the free world is on their side.”

He said he was thinking today of Kara-Murza, a friend with whom he had been corresponding during his sentence, about the other prisoners, and especially about Yulia Navalnaya—Alexei Navalny’s widow, whose arrest was ordered by a Moscow court last month, even as she lives outside of Russia.

“Navalny’s death was not in vain,” Sharansky said. “The determination of people in the West to negotiate became much stronger after his death. They understood we have to save these people.”

But it was not in vain in a more global sense, in the eternal war between liberty and tyranny: “He played a tremendous role by showing he wasn’t afraid.”

To support more of our mission, become a Free Press subscriber today:

All of this could have been avoided were it not for the neo-con/neo-dem fever dreams & fool's errands.

None of knows what is really going on behind the scenes. Anyone who thinks they do is sorely mistaken. All governments lie--all of them. I'm sure Evan Gershkovich is so happy to be home. What is reported and what actually is true is very often different. I would love to see Evan interviewed however he may not be allowed to speak and who would blame him? sabrinalabow.substack.com