The Free Press

The last time I peered through my father’s telescope was in February 1986. We were in our driveway in Palos Verdes, which juts out into the Pacific and is 18 miles south of the glare of downtown Los Angeles—far enough away that you can see the sky when you look up.

Halley’s Comet was racing toward its perihelion—the point in its orbit at which it is closest to the sun—at about 122,000 miles per hour, or 34 miles per second. It looked like a small, silver-gray smudge.

We had only a few hours until the smudge would disappear for another 76 years. I was 13, and it was possible that I would see it again, if I made it to 89. My father was 44. “The accident of the years of our births,” he said quietly.

He had built the telescope when he was 15 in his parents’ apartment in Forest Hills, Queens, and lugged it to medical school in Syracuse and then Boston and Pittsburgh and eventually southern California.

He thought about space the way he thought about mathematics or analytic philosophy or the Torah or Mozart’s twentieth piano concerto, which he sometimes played at night when my sister and I were going to bed. It was beautiful and complex and infinite, and how could you not want to explore that, know where it came from, know where we came from?

We will soon know a little more thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope, which NASA blasted into space on Christmas 2021 and is now about 1 million miles from Earth, revolving around the sun.

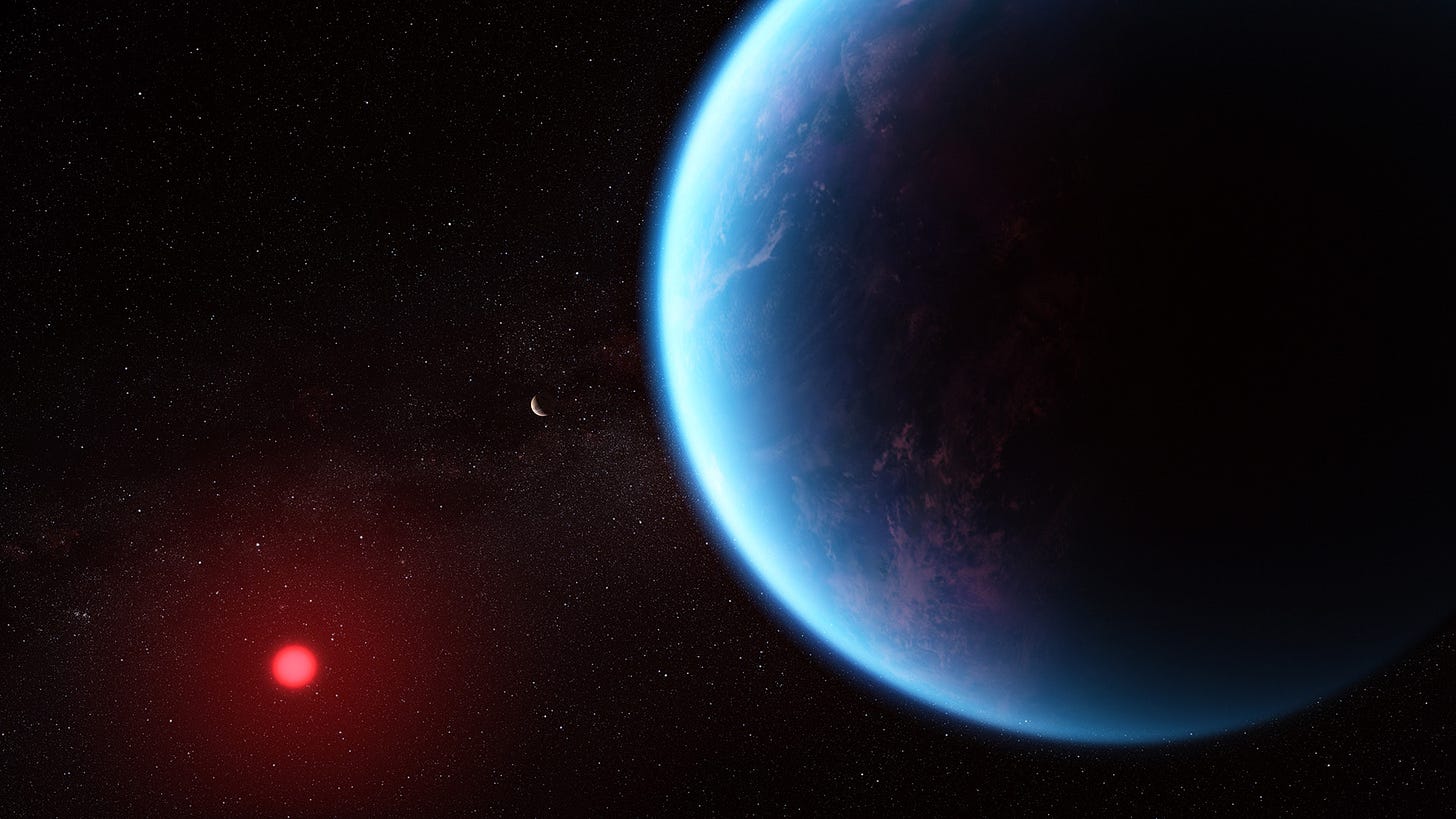

A few months ago, the space telescope hoovered up several as-yet-unreleased images of K2-18b, an exoplanet—meaning a planet outside our solar system. K2-18b is 120 light-years from Earth and, importantly, resides in the habitable, or Goldilocks, zone around the star it orbits. Not too hot, not too cold, it may be just the right temperature for an Earth-like atmosphere that might—might—include life.

Until the 1990s, human beings didn’t know exoplanets existed. Now, we know there are 5,000-plus in our galaxy alone; in the wider universe, astronomers believe there may be as many as 40 billion in the habitable zone.

“There might be simple life all throughout the galaxy,” Jessie Christiansen, an astrophysicist at Caltech and chief scientist at the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, told me. She meant microbes, bacteria, single-celled organisms.

Alexei Filippenko, a UC Berkeley astronomer, told me in an email: “If there is life on K2-18b, it would demonstrate that life on Earth is not unique—a very important discovery.” He added: “Perhaps it would change the religious outlooks of some people, but not others. It depends on whether one subscribes to the belief that God made Earth unique in terms of life.”

Whether there is intelligent life is the big question, Jessie Christiansen said. That is, organisms with brains or brain-like structures.

Astronomers are now poring over the images from the James Webb Space Telescope, and in a few months we’ll know whether the molecule dimethyl sulfide is found in K2-18b’s atmosphere. If it is, the odds that there’s life on K2-18b will have jumped.

And if there’s life, suddenly the underlying threads binding together our existence will become a little less mysterious. We will inch closer to knowing where it all started—which is to say, who we are.

Nikku Madhusudhan, the Cambridge astrophysicist who was the first to glimpse the images of K2-18b, told me: “It was surreal, overwhelming, and humbling at the same time.”

He added: “You are literally the first person looking at this outside world. You are no longer one scientist but a representative of the planet seeking to find the truth about the universe.”

Because it takes time for light to travel, when we look at the sun from Earth, we’re seeing a past version of it. “You see the sun not as it is now, but as it was about 8.3 minutes ago, because it took 8.3 minutes for light to reach Earth from the sun,” says Alexei Filippenko.

The farther away something is, the further back in time we are looking. “You see the stars as they were tens or hundreds of years ago. You see other galaxies as they were millions or even billions of years ago. The finite speed of light thus gives us a movie of the history of the universe.”

Staring at the images of K2-18b coming to us from the space telescope, therefore, “really is like traveling backward in time.”

When I thought about the fictional, or not so fictional, aliens on K2-18b gazing back at us, I imagined them seeing the Earth circa 1904. Decades before my parents were born, grew up, left New York, created a life on the peninsula pushing into the vast ocean; and Halley’s Comet had returned and went away and returned again; and my sister and I migrated across the continent and the world and entered the new century and met our spouses; and my father became ill, and we started families, and he declined slowly across the course of a decade, and died one afternoon a few blocks from the Pacific.

I imagined staring at an Earth in which my family had yet to be created.

Of course, this is not what one is supposed to care about when gazing at exoplanets. What matters is the nature of life and our place in the universe and how it all came to be—and when I thought about K2-18b, I remembered my father narrating as I stared through the scope at Halley’s Comet 39 million miles away. The smudge of ammonia, carbon dioxide, ice, and rock that was a little more than 9 miles long and 5 miles wide and about to disappear for the rest of his life, and maybe mine.

“I’ve known this was coming for most of my life,” he said, “but somehow there’s something shocking about it.”

He would have been overcome with excitement thinking about life on another planet. All the shapes and lights and ancient constellations starting to come into focus. The piecing together of all the mysteries that lead, ineluctably, back to the greatest of ur-mysteries: How is it that there was nothing and then something?

“It will almost be a religious experience for me,” Jessie Christiansen, at Caltech, said, of finding life out there. “I have dreamed about it and thought about it.”

She added: “I am scared that it’s true.”

And then: “Is it more terrifying that we are alone, or that we aren’t alone?”

She reminded me, in the best way, of my six-year-old, Ivan, who recently told my wife and me he wants to be an astronaut. He also wants to be a professional football player and live in a Lego mansion, but the astronaut thing is a thread that courses through bath time and story time and breakfast and dinner. It’s a constant. My father would be pleased.

Ivan asks me, routinely, how cold it is on Pluto and Neptune, or how hot it is on Mercury, or whether there are human beings in other solar systems. He’s taken to saying “in my lifetime” a lot—as in, “You might not live on Europa, but in my lifetime, we will.”

Recently, I told him about K2-18b and the possibility of life on this exoplanet that would take us more than a million years to get to, and we talked about parallel amoebas in parallel oceans on a faraway rock. He was in the bath. He was fascinated. He told me, again, that he wanted to live on Neptune or Uranus, which he pronounced yer-anus, which he thought was funny; and then he said, “What if there’s an ocean? Or fish? What if there are people there who are wondering who we are—right now?”

Peter Savodnik is a writer and editor for The Free Press. Follow him on X @petersavodnik, and read his stories here.

If you have a unique perspective on space, life beyond the solar system, or stargazing, please write to us at letters@thefp.com.

To support our work, become a subscriber today:

The headline is flat wrong. It would be closer to the truth to say, "Astronomers May Have Found a Planet Hospitable to Life." But being hospitable (and even that is still far from clear) is a long way from actual evidence of life, of which there is none. There are many ways to define the "habitable zone," and the odds are high that this planet, while it may fit some definitions, fails others and will prove to be in the end uninhabitable by life as we know it.

A beautiful piece of writing.