The Free Press

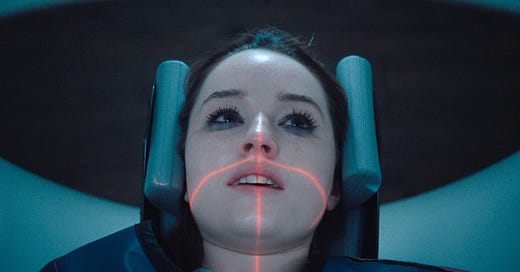

A young woman, dressed in a medical gown and with twin smears of tear-smudged mascara under each eye, is gasping and sobbing, trying to describe the pain that is radiating inside her head. It feels like “stabbing,” like “fire ants”; it feels “structural, not neurological.” It feels, she says, like “there’s something in there.”

You can’t see who she’s speaking to, but her desperation implies that no one believes her.

This is the first scene of Apple Cider Vinegar, the brand-new Netflix drama marketed as “a true-ish story based on a lie.” The sobbing woman is Belle Gibson, a former wellness influencer from Australia, played by Kaitlyn Dever.

But in this moment, she could be anyone, and this scene could be taking place anywhere—because Belle is in a kind of pain that many women will recognize. Not the fire ants in your head kind, but the kind where you’re desperately sick, and desperate for help, only to be treated with skepticism by doctors who refuse to believe that what you’re feeling is real.

The twist, in this case, is that the pain isn’t real—and not only because this is a Netflix series that fictionalizes Belle Gibson’s story. In real life, she did visit a clinic, and she did receive an MRI—and then she claimed that it revealed a malignant brain tumor, when the truth is, it didn’t.

This is the massive lie that the true-ish story of Apple Cider Vinegar is based on.

Gibson amassed millions of followers—and dollars—with her incredible story: that at the tender age of 21 and with no medical background, she healed her stage IV brain cancer through alternative medicine and clean eating. But inconsistencies in her story eventually attracted a growing chorus of critics, and after two years, the narrative on which she’d built an entire career fell apart: In 2015, Gibson admitted that she’d faked her diagnosis. Since then, she’s stayed out of the public eye.

Apple Cider Vinegar is a smart, glossy, and bitingly funny dramatization of Gibson’s rise and fall, but the true story is somewhat grimmer, given that Gibson was promoting her baloney medical biography and phony cures to real people, including actual cancer patients. While there’s no evidence that anyone died because they eschewed traditional medicine in favor of Gibson’s alternative therapies, a civil case brought against her by a consumer protection agency in the Australian state of Victoria led to her being found guilty of misleading and deceptive conduct. She was punished with a $410,000 fine (approximately $250,000 U.S.)—which she still hasn’t paid.

Gibson’s remarkable story of having cured her brain cancer by eating fruits and vegetables was just the tip of the deception iceberg. She told people she was fundraising for charitable causes, like cancer treatment for a 5-year-old boy—whose family later said they never received a cent from her. She claimed to have had open-heart surgery; she said the HPV vaccine caused her cancer. When wellness influencer Jessica Ainscough died of a rare form of cancer in 2015, Gibson showed up at the funeral and made a huge scene, sobbing hysterically—even though she and Ainscough had only briefly met.

But despite knowing all this, when I watched those opening moments of Apple Cider Vinegar, Belle’s suffering didn’t just feel extremely real. It felt completely relatable—as the stories of medical con artists so often do.

With her bogus medicines and fabricated illness, Gibson represents a potent crossbreed between two ubiquitous types of scammer: the Munchausen maiden who pretends to be sick, and the snake-oil salesman who claims to hold the cure.

In the former group are women like Amanda Riley, who raised more than $100,000 by faking a Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis. Her story has also been recently recreated in a glossy docuseries, Hulu’s Scamanda. There’s also Ashley Kirilow, a Facebook fraudster who in 2008 scammed her audience out of thousands of charity dollars after falsely claiming to have terminal cancer. The snake oil category includes countless Instagram quacks with flowing hair and chiseled abs, hawking smoothies and supplements to "reduce inflammation.” But it also includes numerous celebrities, peddling fitness and wellness products of varying (and sometimes dubious) quality.

Then there’s Kim Kardashian and her detox teas, Jessica Alba and her organic baby brand and, of course, Gwyneth Paltrow—who has famously and repeatedly come under fire for her advocacy of questionable alternative health practices such as “vaginal steaming."

If the creators of wellness empires are almost invariably female, then so too are their customers: starstruck women who subscribe to their content, share their posts, and dutifully buy whatever they’re selling, from supplements to life coaching sessions to a $449 baseball cap that’s supposed to help combat baldness.

And if all of this seems a bit silly, it’s also understandable: There is a long and unhappy history between women and the medical establishment. In its early days, female illness was viewed as an explicitly moral issue, and female bodies with a mix of incuriosity, skepticism, and suspicion.

In the Victorian era, physicians believed that virtually every medical condition in women—from scoliosis to anemia to mastitis to epilepsy—was tied to sexual immorality, and would accuse afflicted patients of being compulsive masturbators. Darwin-obsessed anatomists declared that women’s smaller skulls and broader pelvises were incontrovertible evidence that they were congenitally stupid, suitable for breeding and not much else. Less than a hundred years ago, women suffering with everything from personality disorders to painful periods were still routinely diagnosed as hysterical by doctors, and imprisoned in mental institutions; and as recently as 1967, some doctors were still “treating” these women by giving them frontal lobotomies.

And while the medical establishment has ignored, antagonized, and institutionalized women, there has always been a motley crew waiting to profit from our fear: snake-oil salesmen, con men, and quacks marketing tinctures and supplements and elixirs explicitly to a female consumer. In the Victorian era, one such man—who called himself “Dr. Pierce”—advertised his products to women in the pages of newspapers and magazines, taking a markedly conspiratorial tone.

One ad that ran in newspapers nationwide in 1896 reads: “Doctors are often handicapped by the mere fact that when treating the diseases of women, they suggest and insist on ‘examinations’ and ‘local treatment.’ A great many of them do not know that this is absolutely unnecessary.”

“Diseases that all other medicines had failed to cure, have been perfectly and permanently cured by the use of ‘Favorite Prescription,’ ” promises another.

This is the same message employed by influencers like Gibson.

In Apple Cider Vinegar, Belle announces the launch of her wellness brand with an earnest video monologue to her followers: “When I was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, I didn’t know where to turn or who to trust. I felt unsupported, unmotivated, and uninspired. You may not have cancer, but maybe you feel that way too, and you know what? It’s not okay.” And then, the sales pitch: “Download my brand-new app, The Whole Pantry, today, and change your life, one meal at a time.”

This message might be even more seductive today than it was in 1896, at a moment when the public’s trust in health experts and institutions is at an all-time low. The damage done to their credibility during the pandemic is difficult to overstate, marked by policies that seemed to be less about making people healthy than crushing them into compliance. Vaccine mandates, forced masking, the suppression of the lab leak hypothesis: This rampant authoritarianism creates a massive trust vacuum that is ripe for the Belle Gibsons of the world to fill. Not just because of what they sell, but because of who they are: not an institution, not a corporation, but a person, just like you. Traditional medicine and Big Pharma wanted to control me, she might say, just like they want to control you. But I broke free, and healed myself—and you can too.

The desire of people, especially women, to reclaim authority over their health is embodied in this moment by the Make America Healthy Again movement, the instincts of which are often broadly correct and compelling—albeit sometimes overshadowed by the conspiracy theorizing of its lunatic fringe. Like Gibson, those who subscribe to MAHA will emphasize that the medical industry isn’t actually designed to promote health, per se. After all, pharmaceutical companies don’t profit from making you well; they do it by making you a patient, living from one dose to the next, and paying into their pockets for the rest of your life. Both wellness gurus and MAHA moms will promote, rather than drugs, nutrition—an idea whose appeal to the average American is easy to understand. Pharmaceuticals are expensive, inscrutable, their recipes jealously gatekept by massive corporations, while food is cheap, accessible, and available without a prescription. Virtually nobody can synthesize doxorubicin in their basement, but anyone can put a bunch of kale in a blender.

Of course, kale, despite its many fine qualities, will not cure your terminal cancer. But this is only a problem if you have terminal cancer, which most of the people who follow these modern-day health gurus do not. The average fan of someone like Belle Gibson isn’t critically ill; she may not even have any real concept of what “getting healthy” might look like. She’s just trying to do something, to feel like she’s in control and improving her life.

And the thing is, she does. Because what wellness influencers understand is that it feels good to make a change, to take charge—especially if you’ve previously felt like you were at the mercy of a faceless, impersonal system that doesn’t listen, doesn’t care, doesn’t even know you.

Belle Gibson listens. Belle Gibson cares. She’s telling you she’s been where you are, she knows your pain, and she’s making you a promise: There are brighter days ahead. The great secret, the great tragedy, and the greatest scam of all is this: These alternative medicines probably won’t heal you.

And yet: Don’t you feel better already?