Hello readers! Bari here. Tim Urban is the only cartoonist who has elicited an existential crisis in me. It’s not because he’s some great illustrator. His drawings are comically simple stick figures, or, if he’s feeling fancy, maybe a chart.

What makes them so affecting is the way he is able to capture and distill the most complex and profound questions we face. Questions like: What does it mean to be human? Are we spending our finite time on Earth wisely? And do we even grasp how finite that time is?

By capturing the length of our days in, say, the amount of times we have left to swim in the ocean; the books we have left to read; or the dumplings we have left to eat, Tim takes an abstract subject like time and makes it tangible.

If you click here, you’ll see just what I mean. (And while you’re at it, tool around Tim’s blog, Wait But Why, which is full of everything from posts on AI to the Fermi paradox to marriage.)

Suffice it to say, I’m a fan. And now Tim has written a book called “What’s Our Problem? A Self-Help Book for Societies,” in which he describes how and why we’ve lost our collective grip—and how we might regain it.

One of the key themes of the book is self-censorship. How have we arrived at a moment in which more than 63 percent of American college students say their campus climate prevents some people from saying things they believe? How is it that, in our liberal democracy, seven out of 10 say a professor should be reported if they say something offensive?

In the chapter we’ve excerpted below, Tim uses the tale of a made-up land called Hypothetica to show how easily people can be forced into saying—and eventually thinking—the same things. (The piece is longer than our usual fare, in part because of the illustrations, so consider printing it out or saving for this evening over a cocktail.)

And if you come to the end and want to read more, you’re in luck: Tim is offering all Free Press subscribers a 10 percent discount when you buy a copy of his book. Just click the links to directly download the audio or ebook—and the code FREEPRESS will be automatically applied. (If you prefer a Kindle version, you can purchase the book here.)

As always, share your free and uncensored thoughts with us in the comments.

—BW

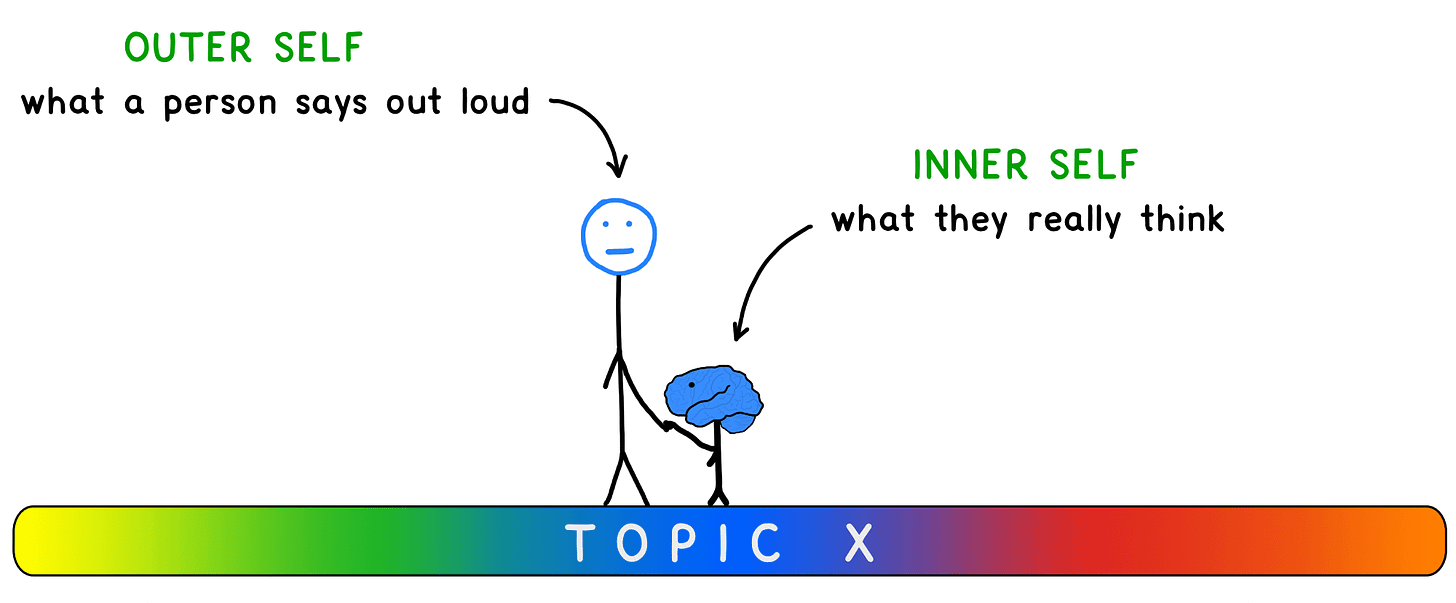

Let’s break every human into two parts: their Outer Self and their Inner Self.

The Inner Self represents what a person thinks; the Outer Self represents what a person says.

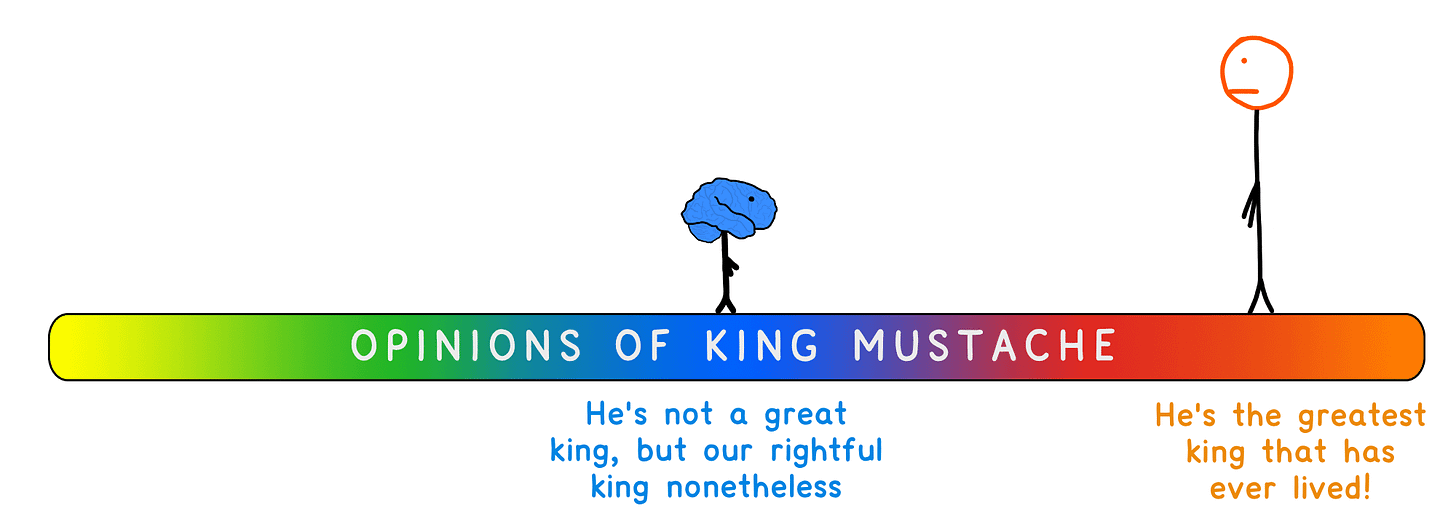

If we take any given topic, we can depict each of their viewpoints by where they’re standing on an “Idea Spectrum,” and by the color of their head:

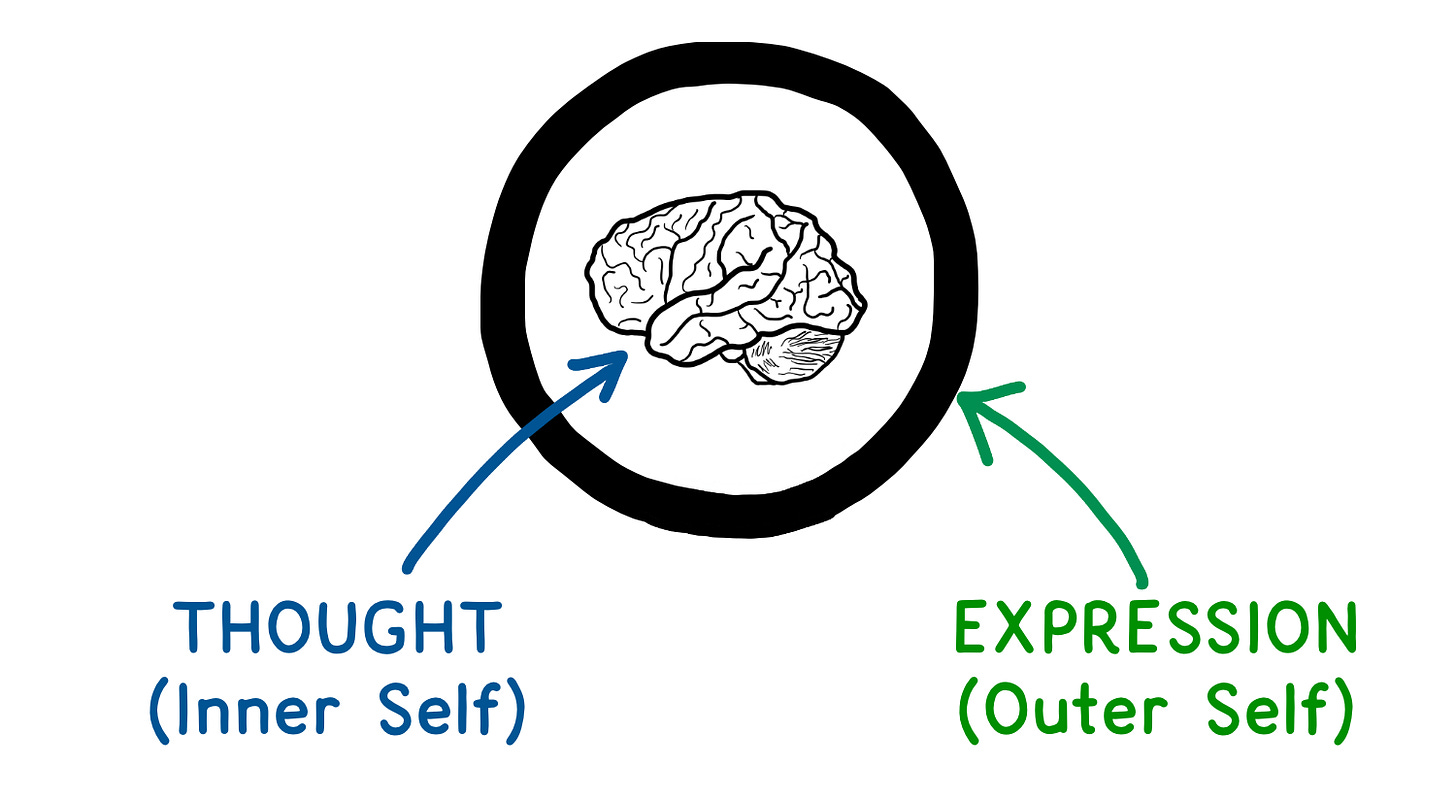

We can combine these using a shorthand notation:

And we can color these to show what a person is thinking (brain color) and what they’re saying (ring color). When a person is being honest and saying what they really think, the two colors are the same, allowing the thoughts of the Inner Self to pass unimpeded through the Outer Self and out into the world.

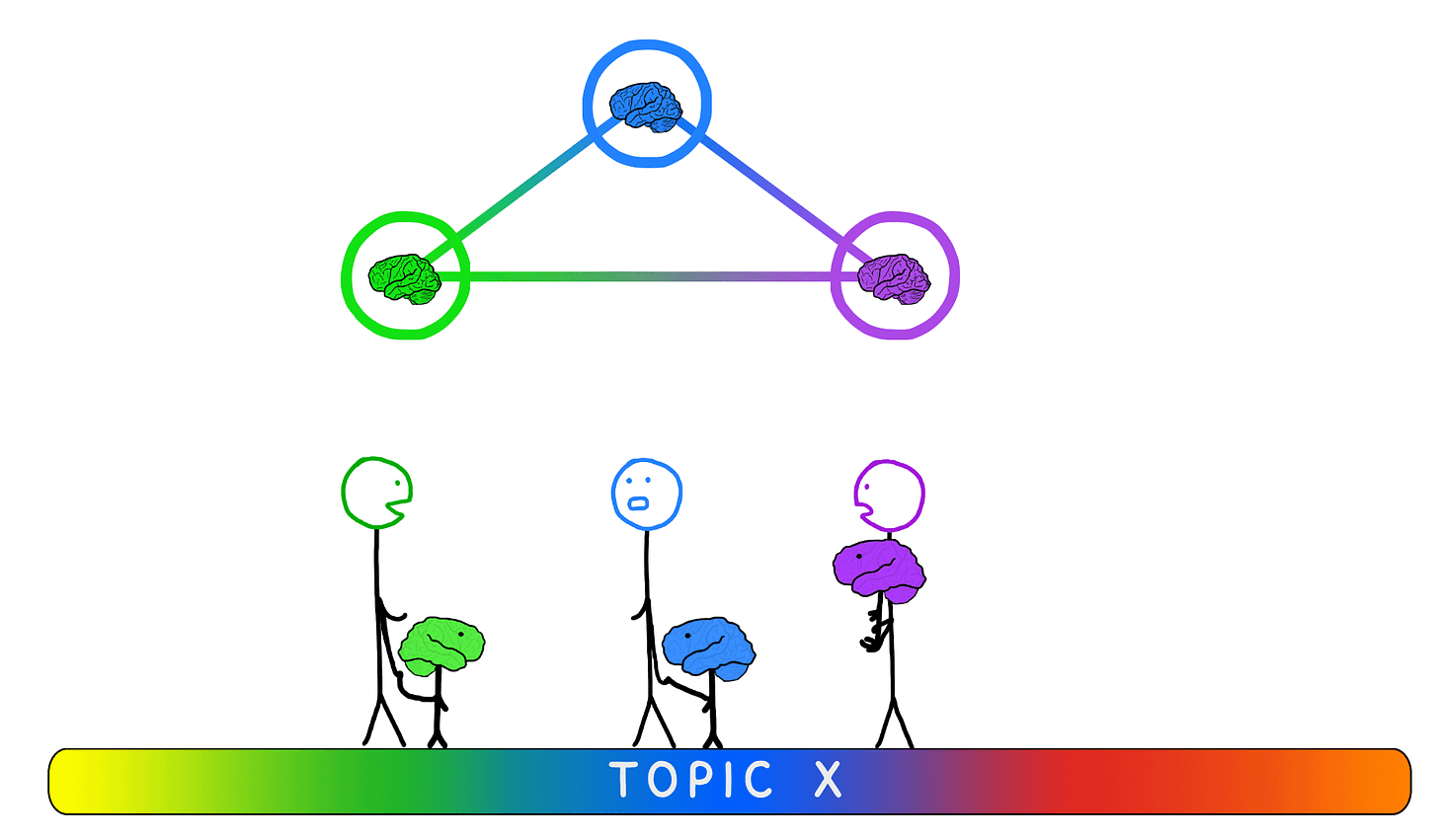

So, for example, when three people are having a conversation about a topic and everyone is saying what they really think, their brains link together into a three-brain thinking system:

Let’s use this system to visualize the story of a land far, far away called Hypothetica, a place known for its vibrant discourse.

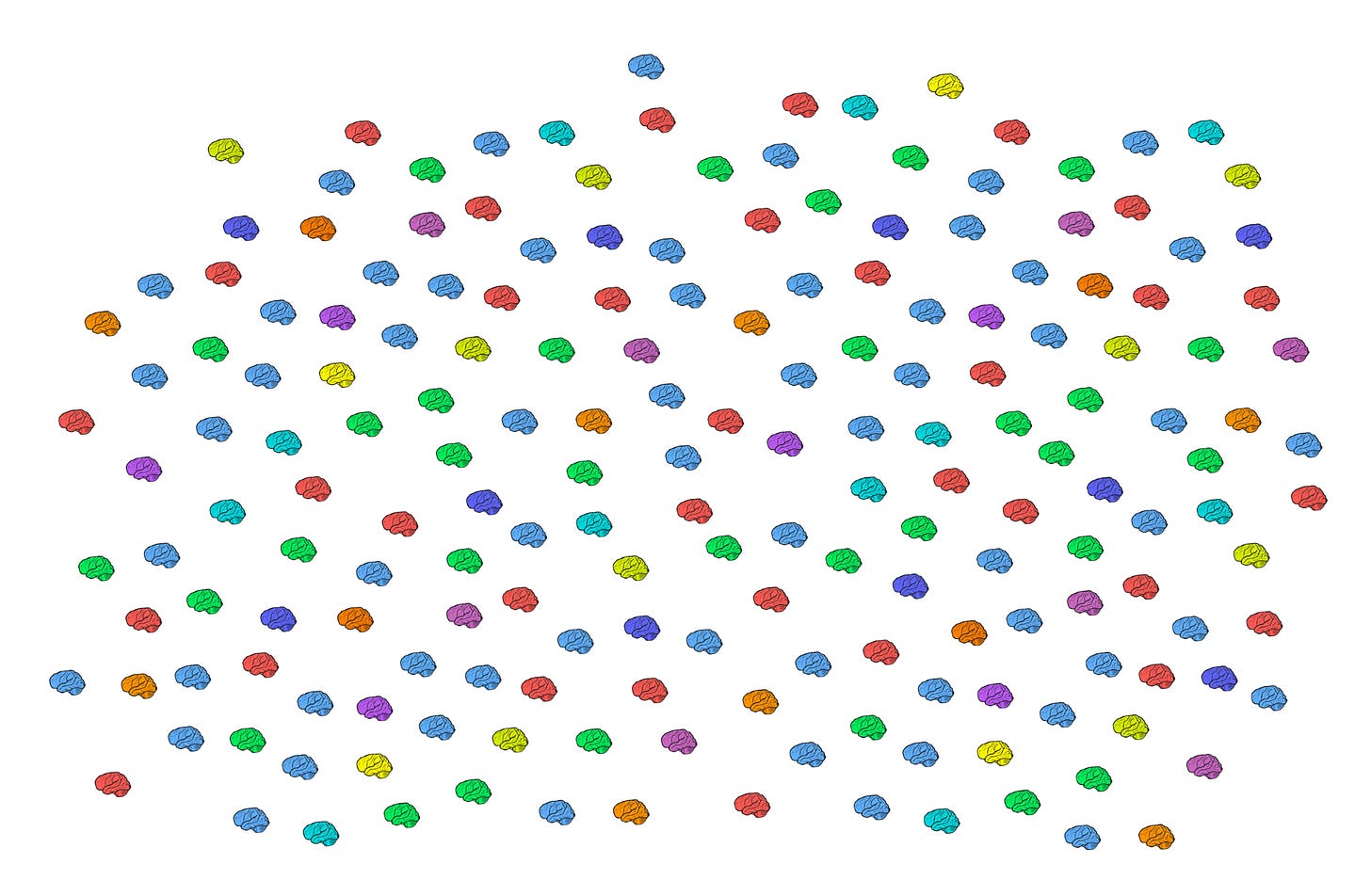

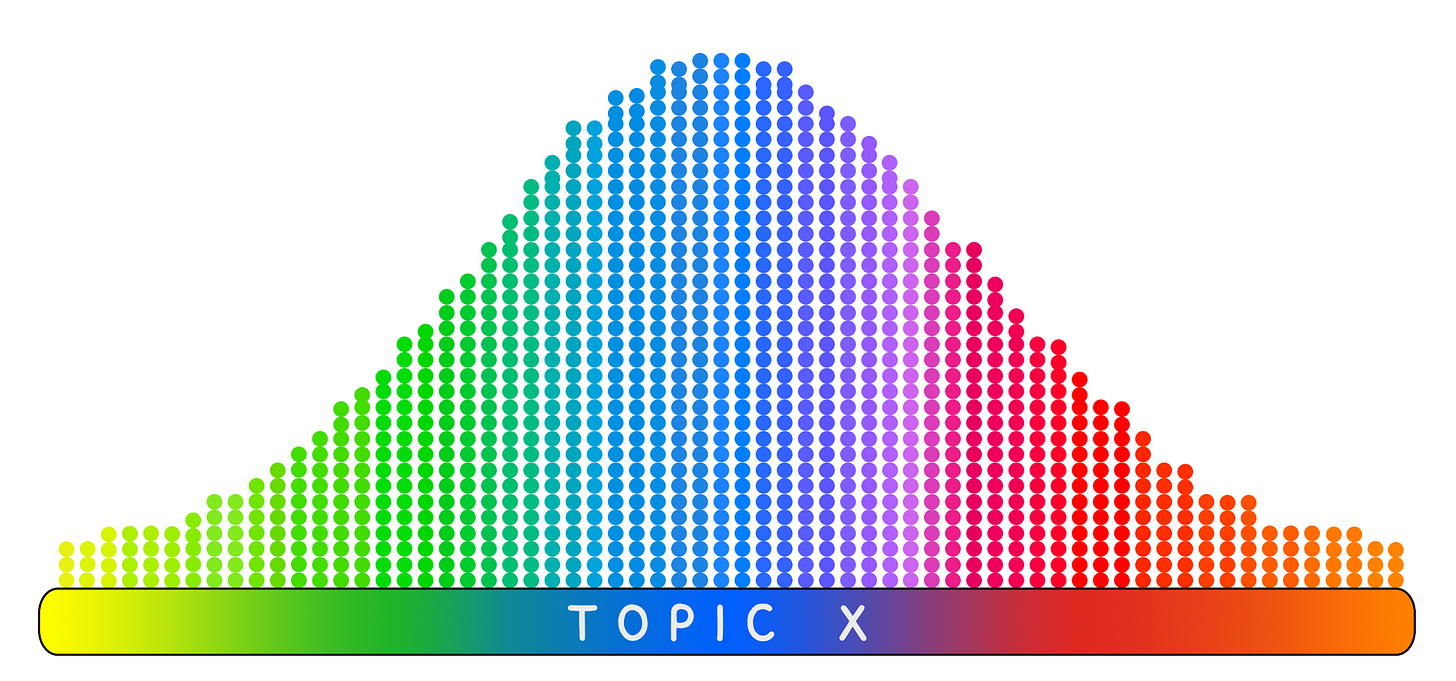

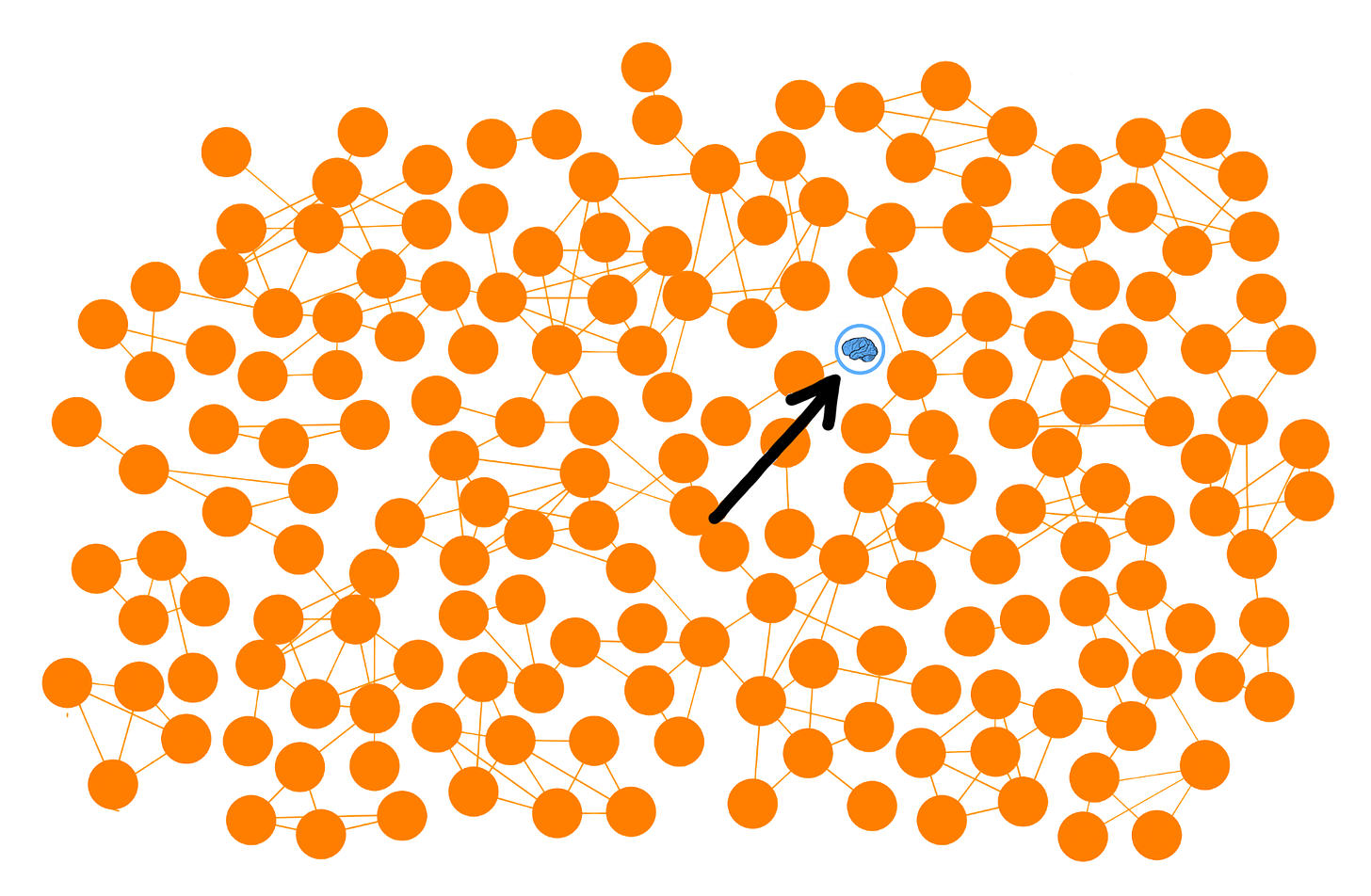

On a particularly controversial topic, the Inner Selves of Hypothetica’s citizens might have looked something like this:

We can organize these Inner Selves by stacking them along the Idea Spectrum:

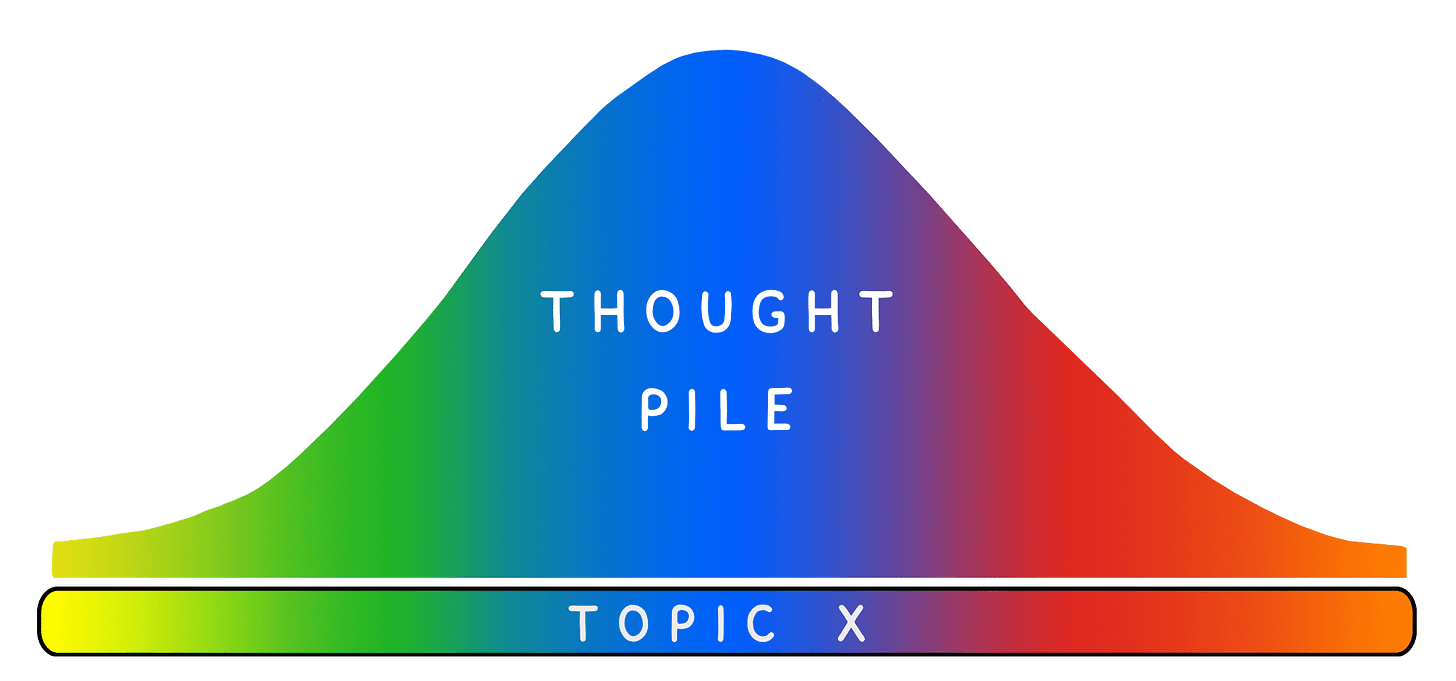

Smoothing it out gives us a visual representation of what Hypotheticans think about Topic X. Let’s call it the Thought Pile.

Human brains can have emergent properties, combining together into larger superbrains. This only happens when the brains actually connect, which they do by way of expression.

Hypothetica’s public venues—its teahouses and amphitheaters—help meld the kingdom’s disparate conversations together into a single larger conversation.

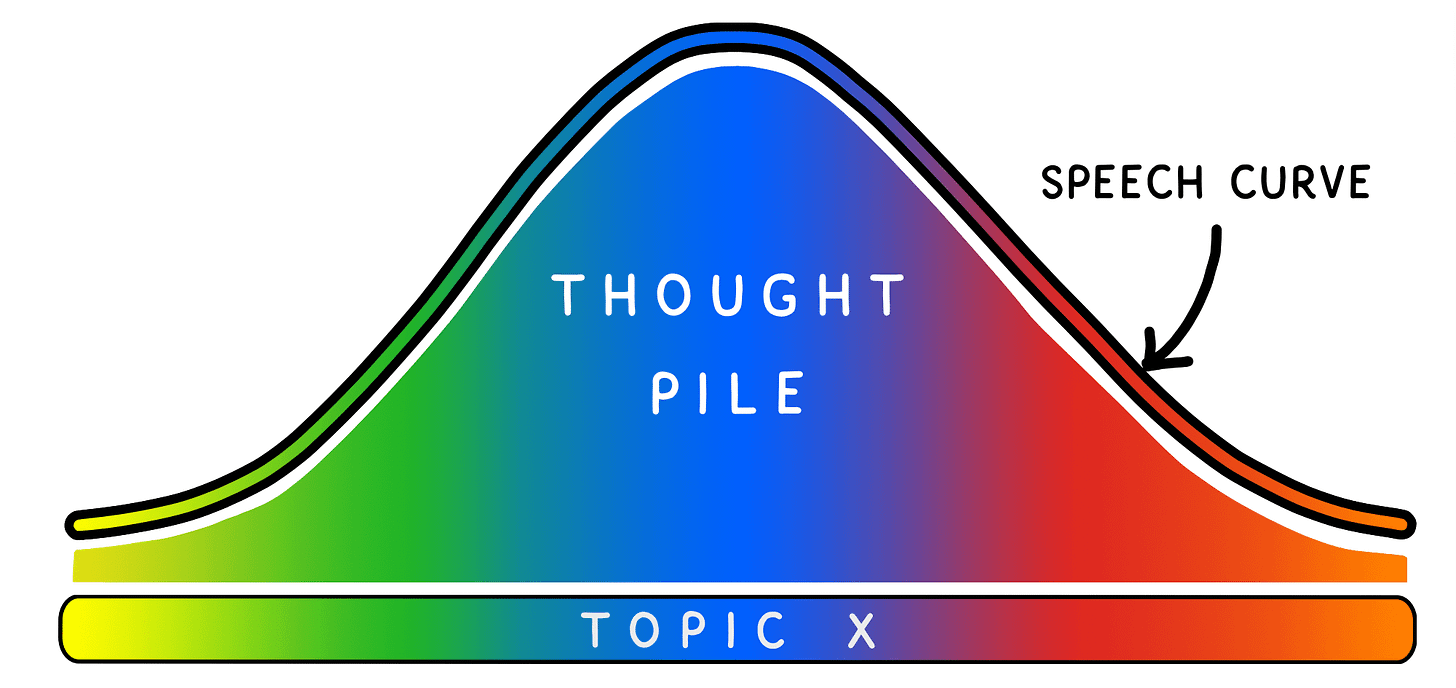

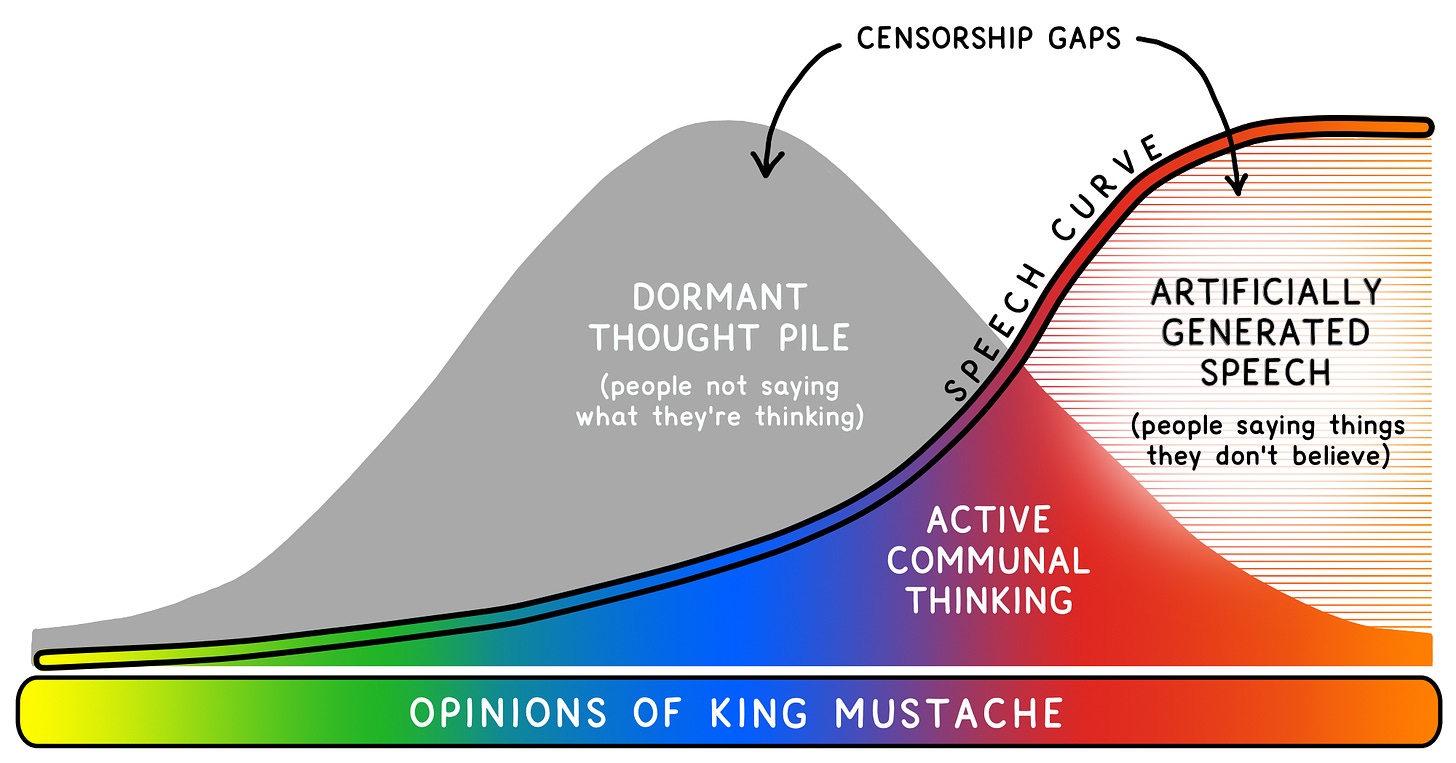

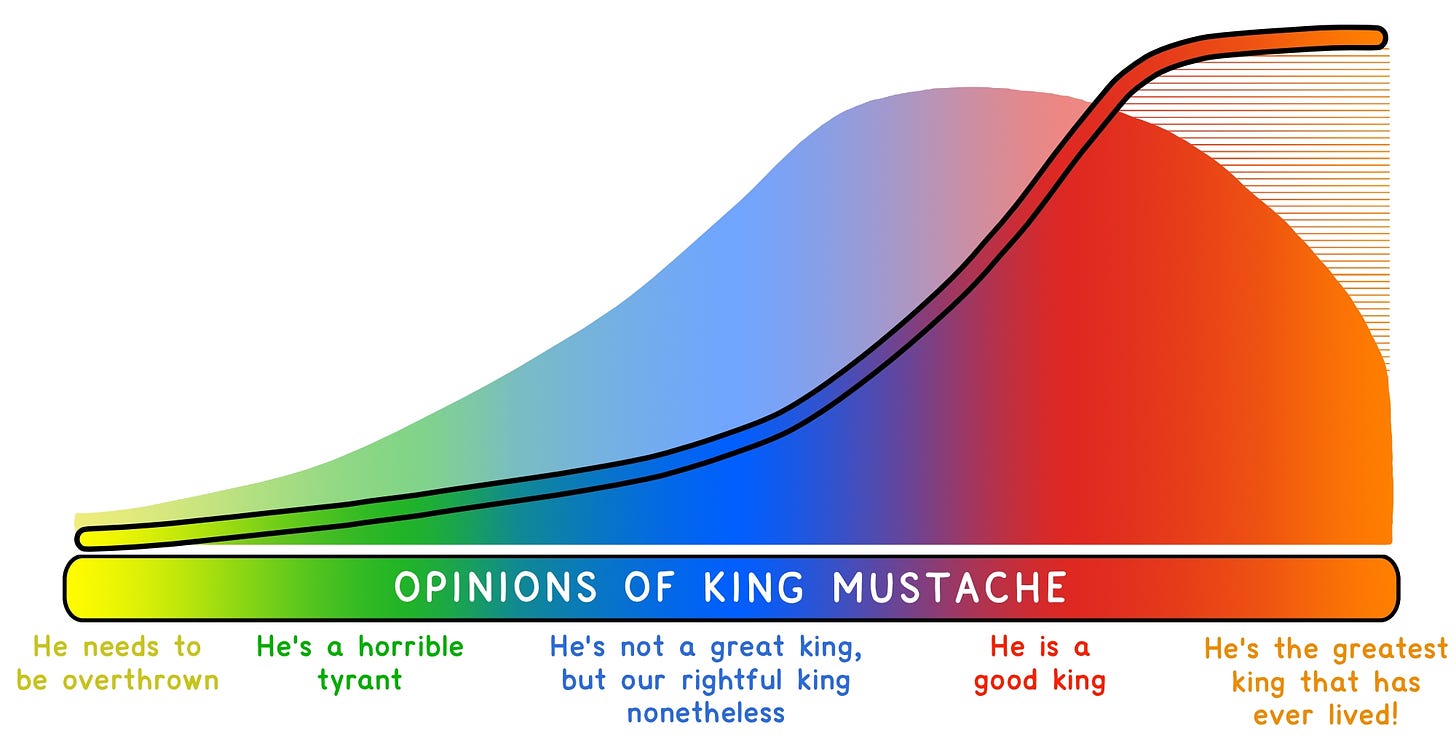

If the Thought Pile depicts what citizens are thinking, we can use a Speech Curve to illustrate what they’re saying. The more a certain viewpoint is being expressed, in conversations and in public venues, the higher the Speech Curve over that point in the Idea Spectrum. So when people are all saying what they’re thinking about a given topic, the Speech Curve matches the shape of the Thought Pile, sitting neatly on top of it:

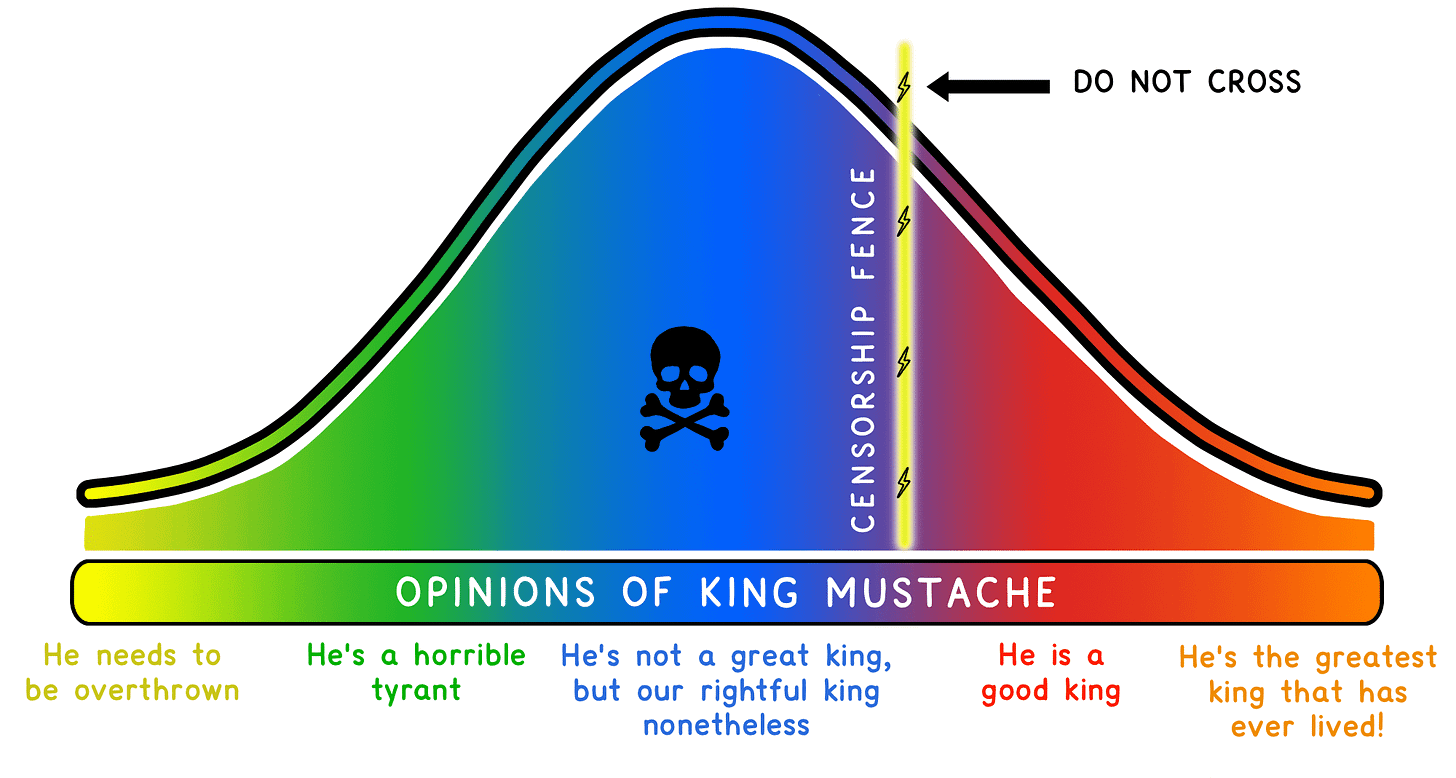

But one day, Hypothetica’s king died, leaving the throne to his son, King Mustache. Unlike his father, King Mustache was highly sensitive to criticism. He issued a decree that made criticizing him illegal—an attempt to lay down an electrified “censorship fence” across the topic that would severely punish anyone who dared to cross it.

The king’s open challenge to the free speech tradition was a pivotal moment of truth in Hypothetica. Would the guards and citizens stand up for that tradition or give in to the king?

Had the police and military stood together against the order, the king’s fence would be proven to be but a figment of his imagination. But the guards carried out the order and people were actually killed for criticizing the king, and the electric fence—and King Mustache’s authority—became very real.

Citizens’ Inner Selves could still think freely, but King Mustache’s now-very scary policy kept everyone’s Outer Selves contained to the reddish-orange part of the spectrum.

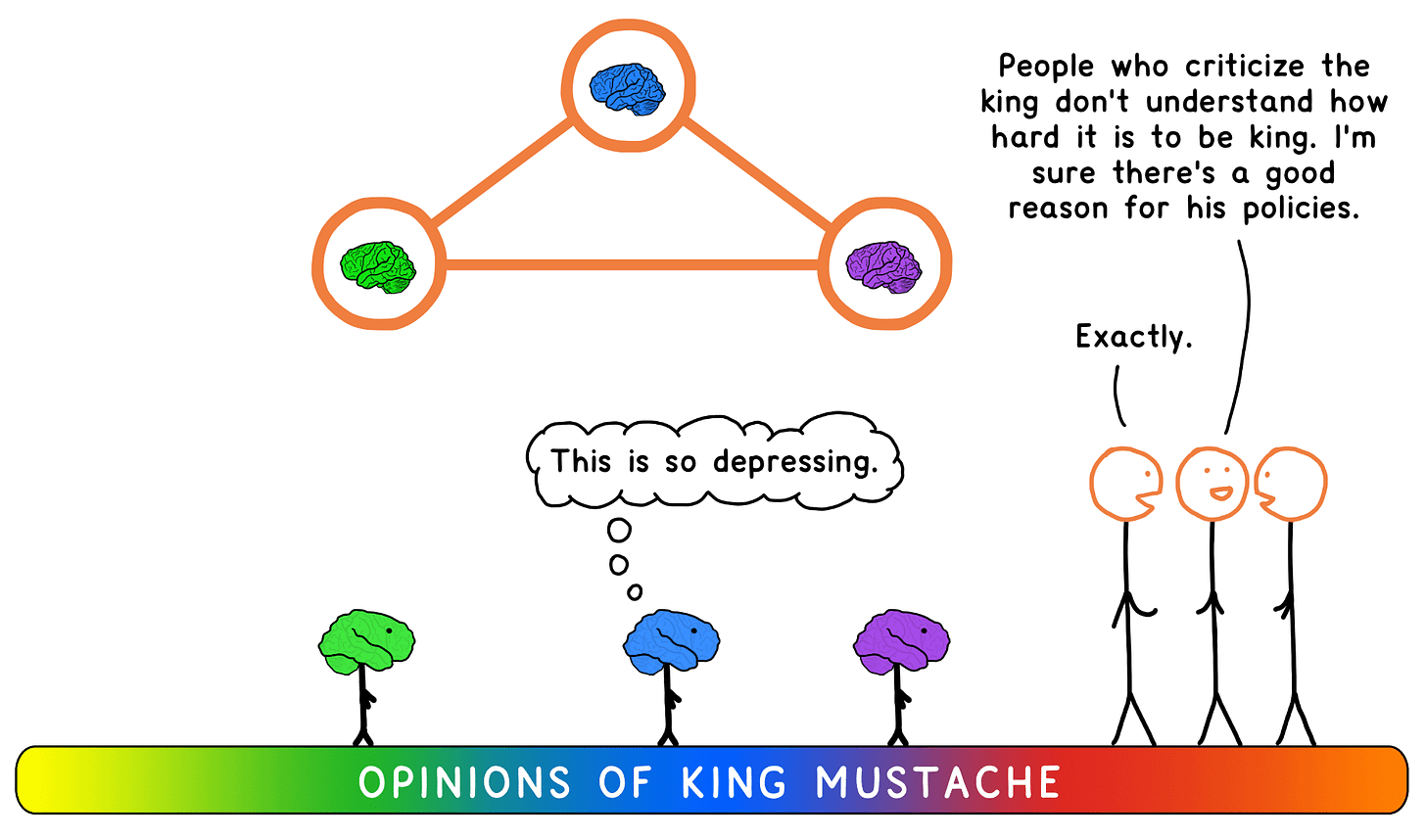

When a person isn’t allowed to say what they think, their ideas become quarantined inside their head, isolated from the outside world. From the communal brain perspective, where each individual human mind is a single neuron in a larger brain, it’s as if the axons of the neurons have been hijacked, and any real neural communication ceases.

The result was that when it came to opinions of King Mustache, Hypothetica now looked like this:

The kingdom’s public venues, with the king’s cudgel looming over them, also quickly fell in line. With people no longer saying what they were thinking, the Speech Curve separated from the Thought Pile. Silenced areas of the Thought Pile fell dormant. What was once a land of thriving discourse and higher-emergent thinking became a rigid echo chamber.

Meanwhile, especially on large platforms, the king’s preferred viewpoints were then repeated ad nauseam—receiving a far brighter spotlight than public opinion and public interest would normally warrant. Censorship takes a single region formed by an aligned Thought Pile and Speech Curve and turns it into three regions by generating these two “censorship gaps”:

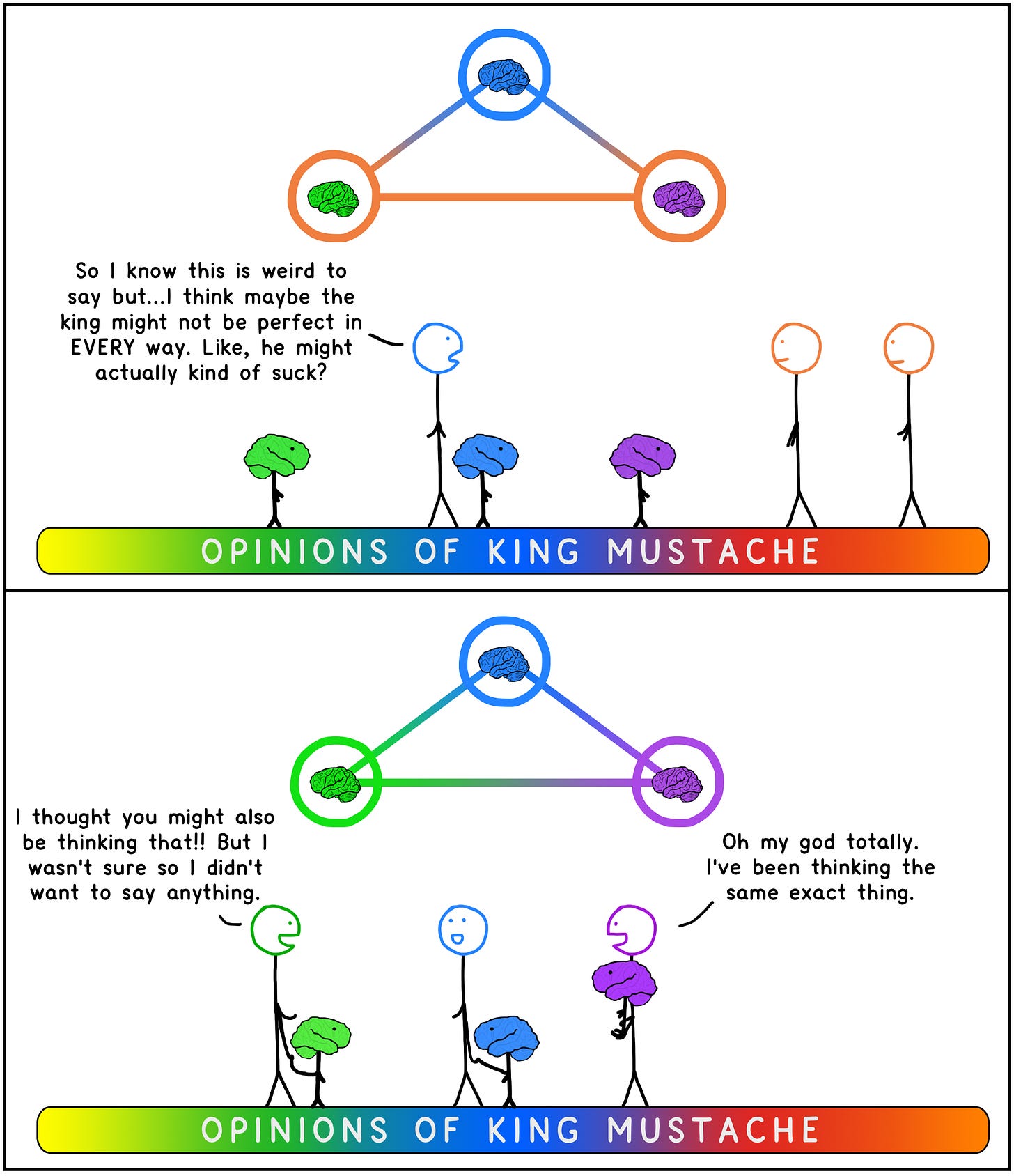

Censorship doesn’t have to be airtight to accomplish its goal. For example, a small intimate group might begin to be honest with each other, forming a tiny, undercover “Idea Lab” within the larger echo chamber:

But if a ruler can block ideas from being spoken in more public spaces, forbidden ideas are still quarantined within small, isolated pockets. If people will speak openly in private but still abide by the censorship rules in public, they appear to everyone else to hold the king’s preferred views.

Containing the expression of banned viewpoints to small groups prevents the viewpoints from traveling anywhere and gaining any momentum within the nation’s superbrain.

We think of censorship as control over what people can say. But the concept of emergence reminds us that superbrains only “think” by way of conversation—which means that censorship is really control over what the group itself can think. For a society, censorship is mind control.

If everyone spoke out against the king, he wouldn’t stand a chance—but that takes a coordinated effort. And if just one person speaks out against the king, they’re a traitor and they’ll be executed. This traps the populace in a kind of prisoner’s dilemma. Without the confidence that everyone will join them in their treason, no one will want to risk speaking out. If someone does speak out, no one will want to join them out of fear that they’ll be the only one to join in, which would spell their own doom. So even if every single citizen wants to overthrow the king, and even if everyone knows everyone else wants to overthrow the king, the censorship policies prevent the overall society from being able to act.

And then something else starts to happen. The illustrations we’ve been using display a cross-section of everyone’s head that shows us what people are both saying and thinking. But for each citizen, what others are thinking is hidden from sight. So if you’re this person—

—despite actually being surrounded by tremendous viewpoint diversity, you may start to wonder if you’re the only person thinking what you’re thinking.

Seeing only everyone’s orange exterior, you might assume everyone actually believes the orange viewpoint.

A phenomenon that psychologists call “pluralistic ignorance” begins to set in: when no one believes, but everyone thinks that everyone believes. Over time, hearing everyone expressing the same viewpoint, people start to doubt their own beliefs and assume that if everyone is saying it, there must be something to it.

As belief in the king’s narrative grows, the iron grip of censorship gets even tighter, as believers become loyal soldiers ready to turn in neighbors who speak treason, even in private. Over time, the Thought Pile itself begins to distort.

Many young Hypotheticans, raised entirely on the king’s version of reality, come to believe wholeheartedly that their king is righteous and his policies noble. They then pass the story into the heads of their own children.

Controlling what people can say controls what the superbrain can think—which eventually leads to controlling what individuals think. Over time, a superintelligent, pluralistic society turns into a single mindless force.

This is the true power of censorship. And once a society succumbs to censorship, they can get stuck in it for a long time.

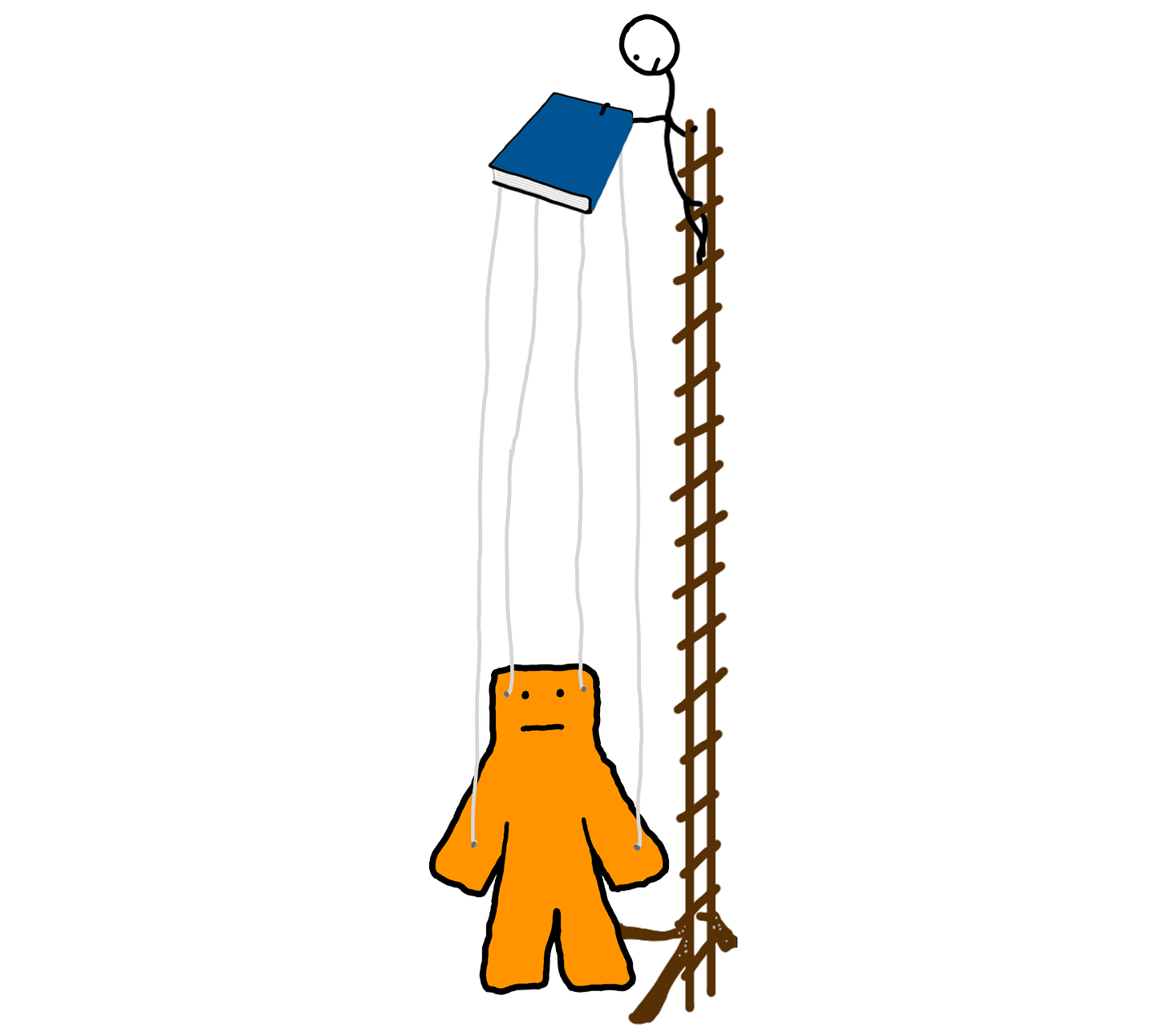

Throughout human history, clever opportunists have discovered that if you could control what people say, you could write the story people believed. You could dictate the values, the morals, and the customs. You could decide who the good guys were and who the bad guys were. You could create the laws, dole out the rewards, and inflict the penalties. If you could write the narrative, the group became your marionette.

The most effective puppet masters came up with depictions of reality that tapped directly into people’s most primitive instincts. Some would stoke fear with stories of imminent danger or invoke rage toward a common enemy to fuel people’s primal fires. Or they might write stories of their own ruthlessness and inflict fear of torture and death on subjects. Others would claim knowledge of the divine in order to bring the afterlife into the picture and drive incentives to astronomical heights.

Stories like these activate behaviors like conformity and obedience that make a population easy to control. They ignite psychology like self-sacrifice and out-group dehumanization that are perfect for tyrants trying to win wars for territory and resources. But none of this works in a society that can think for itself. This, perhaps above all, was the defining insight of the Enlightenment.

Free Speech and the Marketplace of Ideas

The tale of King Mustache—and so many real-world instances like it—is why the U.S. has the First Amendment:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Pulled out from the larger group of First Amendment liberties, we see that the American notion of free speech comes down to ten words:

Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.

In other words, Congress shall erect no electric fences. Congress shall exercise no mind control over the larger society.

These ten critical words mean that speech of any kind is always legal and protected. Well, not speech of any kind. There needs to be a compromise between freedom and safety. When speech actually infringes upon a citizen’s safety, it’s not allowed:

But aside from carefully delineated instances carved out in case law, speech is almost never illegal.

Free speech means that even the most vile and objectionable ideas can be aired freely. This is critical, because governments that enact censorship policies rarely call them “censorship” policies—they usually say they’re banning some form of vile or objectionable speech. And so often, what rule-makers happen to find objectionable is criticism of themselves and their policies. The ability to restrict blasphemy is the ability to censor.

In Hypothetica, we saw how the power to censor became the gateway to other kinds of power. That’s why free speech is often referred to as not just any right but the fundamental right.

Beyond protecting against tyranny, free speech laws open the gates to a dynamic free speech market—the marketplace of ideas. In the marketplace of ideas, scientists freely do their research, philosophers freely philosophize, activists freely protest, journalists freely report, and artists and comedians freely challenge norms and test the edges of what’s socially acceptable. If the market’s “supply” is made up of the ideas of millions of free-speaking humans, “demand” consists of millions of free-listening ears. To win the key currency of the market—attention and influence—ideas have to out-compete other ideas in the market.

In the same way that a free economic market has a natural tendency to push bad products to the fringes while elevating the best, the marketplace of ideas serves as a vast information filter. Ideas are stripped naked and analyzed from every angle. This exposes and embarrasses false or unwise ideas and prevents them from spreading too widely. The marketplace of ideas is messy, and it doesn’t always succeed at sorting right from wrong and good from bad, but it’s a far better system than the alternative: allowing the most powerful people to decide what’s true and what’s good. The marketplace of ideas is like a giant communal brain that allows the country to think for itself and, over time, point the country in the direction of truth and progress.

How the American Brain Learns

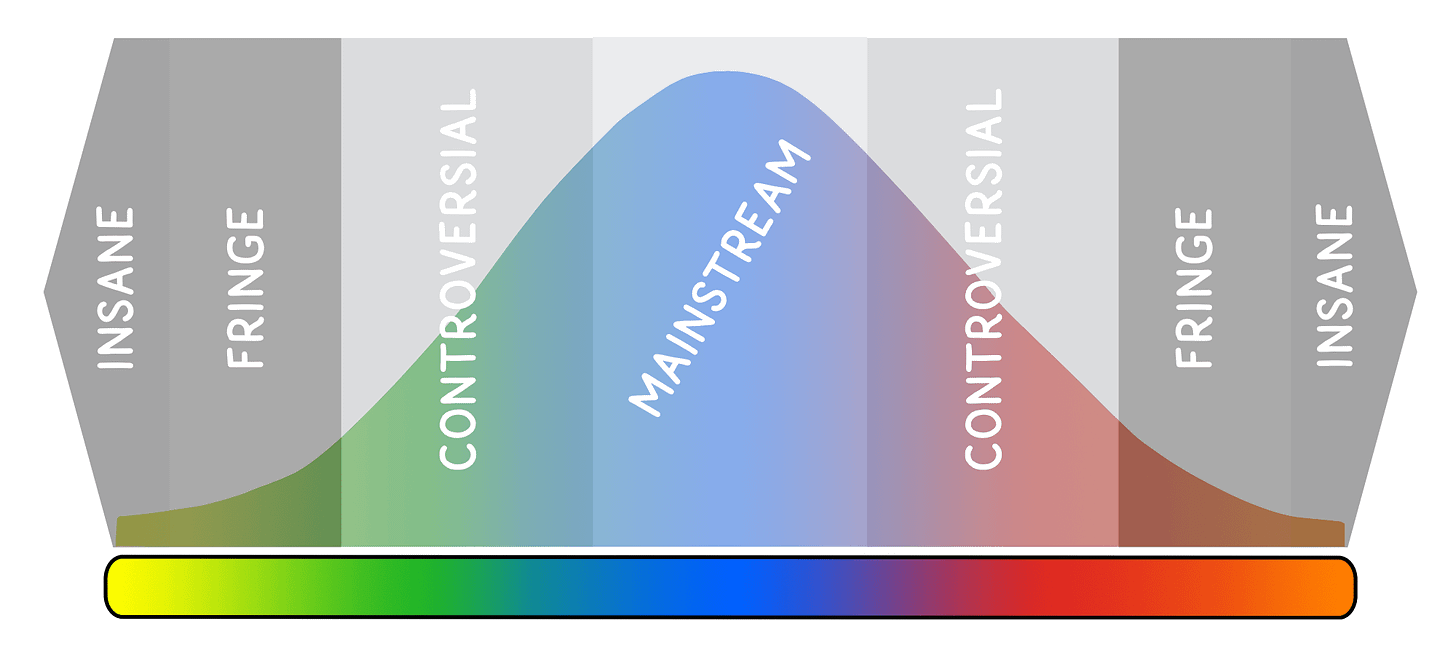

On any given topic, at any given point in time, there will be a wide range of what people believe to be true or good. But typically, the ideas that carry the most power will be those held by the most people—the mainstream ideas.

The mainstream ideas are taught in schools, dictate broad cultural norms, and show up as slogans in political campaigns. Even though plenty of individual citizens will disagree with them, the ideas at the top of the Thought Pile are what the big communal brain “thinks” at any given point in time.

The combination of free speech and representative government means one person with a good idea can freely speak out about it and start a mind-changing movement that, if successful enough, can eventually change the big brain’s mind and drive the country’s evolution. This is how, over time, the giant national brain can make its own decisions, learn new things, and grow wiser.

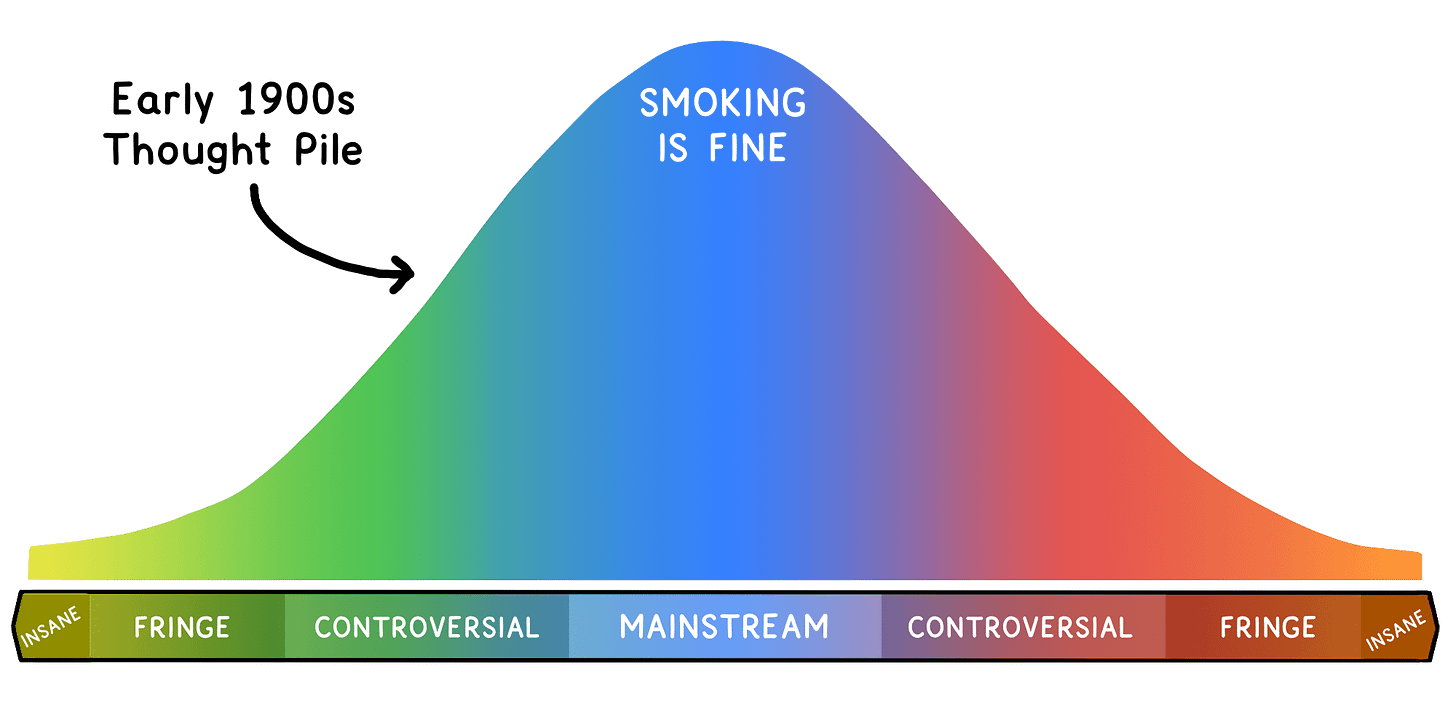

Take the history of smoking. The modern cigarette was invented in the 1880s and exploded in popularity in the U.S. in the first half of the twentieth century. Americans went from smoking an average of 50 cigarettes per adult per year in 1880 to over 2,000 by the mid-1940s.

Throughout these decades, it was a mainstream view among Americans that smoking was a relatively harmless habit.

The communal U.S. brain believed that smoking was harmless—a narrative that was continually promoted through mainstream channels. Ads portraying cigarettes in a positive, beneficial light were everywhere. Cigarettes were culturally cool and commonly associated with movie stars and other icons. You could light up in airplanes, restaurants, offices, hospitals, and most other places.

But then there was this other viewpoint, out in more controversial territory:

Early in the twentieth century, research began to appear linking smoking to all kinds of health problems. And people began to talk about it.

People don’t like having their beliefs challenged or their favorite habits disparaged. Companies profiting from the status quo really don’t like alternative viewpoints. So, the new anti-smoking position was attacked from all sides.

For a while, the attacks were effective. Forty years after the early evidence surfaced linking smoking to cancer, a 1954 Gallup survey found that 60% of Americans answered “No” or “Unsure” to the question “Does smoking cause lung cancer?”

But the marketplace of ideas eventually separates the truth needle from the haystack of falsehoods, and the anti-smoking voices didn’t fade away—they got louder.

In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General issued the first public report on smoking, outlining the negative effects. As evidence piled up about the dangers of second-hand smoke, more people in the marketplace began to protest cigarette smoking being legal in indoor spaces. Parents whose minds had changed about cigarettes became more likely to prohibit their children from smoking. Politicians, noticing the shifting tide of public opinion, began to outlaw cigarette ads and ban smoking in enclosed spaces like restaurants and airplanes.

As American society’s answer to “Does smoking cause lung cancer?” shifted from “No” to “Yes,” the percentage of Americans who smoked dropped from 47% in 1953 to 14% in 2017.

The “smoking causes cancer” advocates conquered the Thought Pile by pulling it toward their viewpoint—and in the process, pulling the Thought Pile away from the “smoking is fine” viewpoint.

As the Thought Pile slid, so did culture, politics, laws, and behavior. All of this happened against the tremendous force of a large industry’s fight for survival. The newer narrative had truth on its side, and in a free marketplace of ideas, truth usually prevails.

The same process that makes the national brain more knowledgeable can also drive its moral growth.

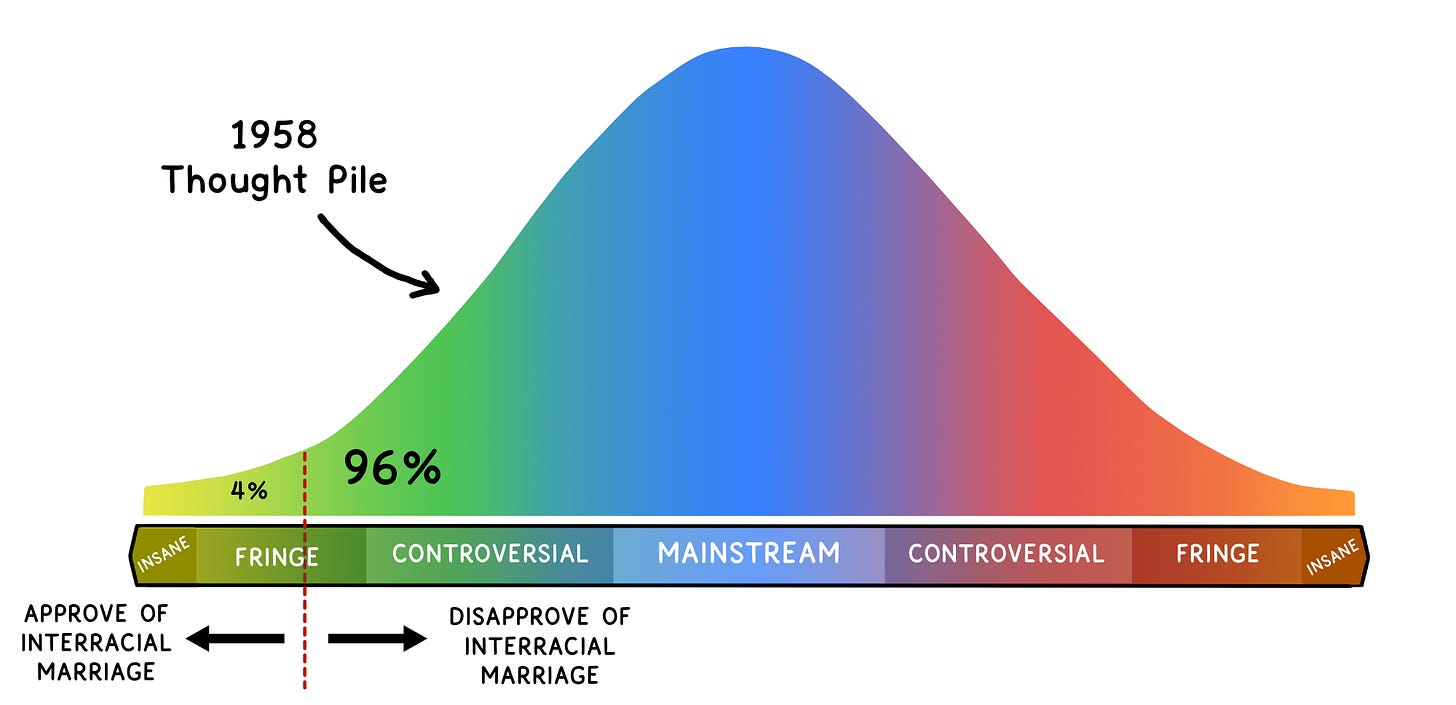

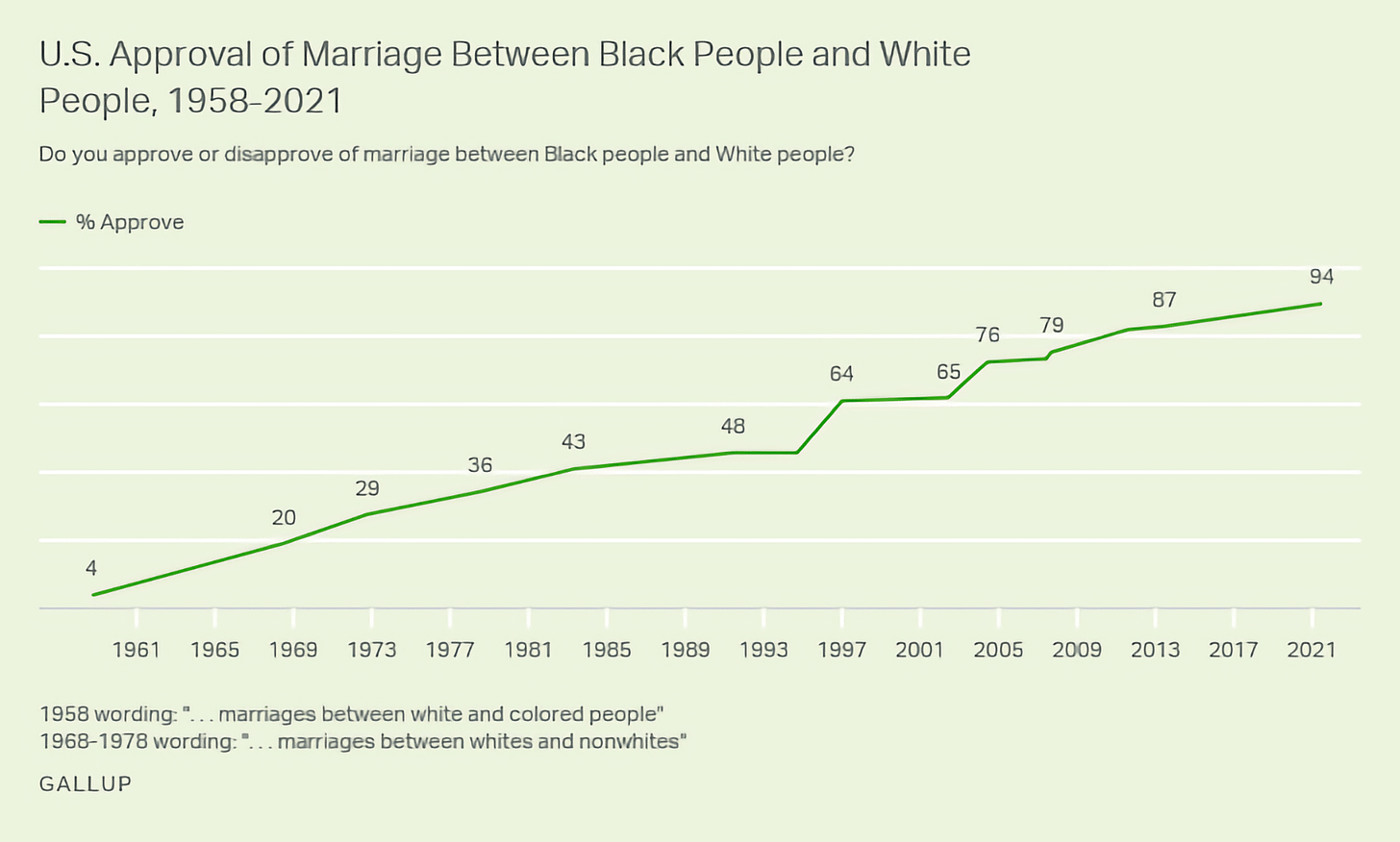

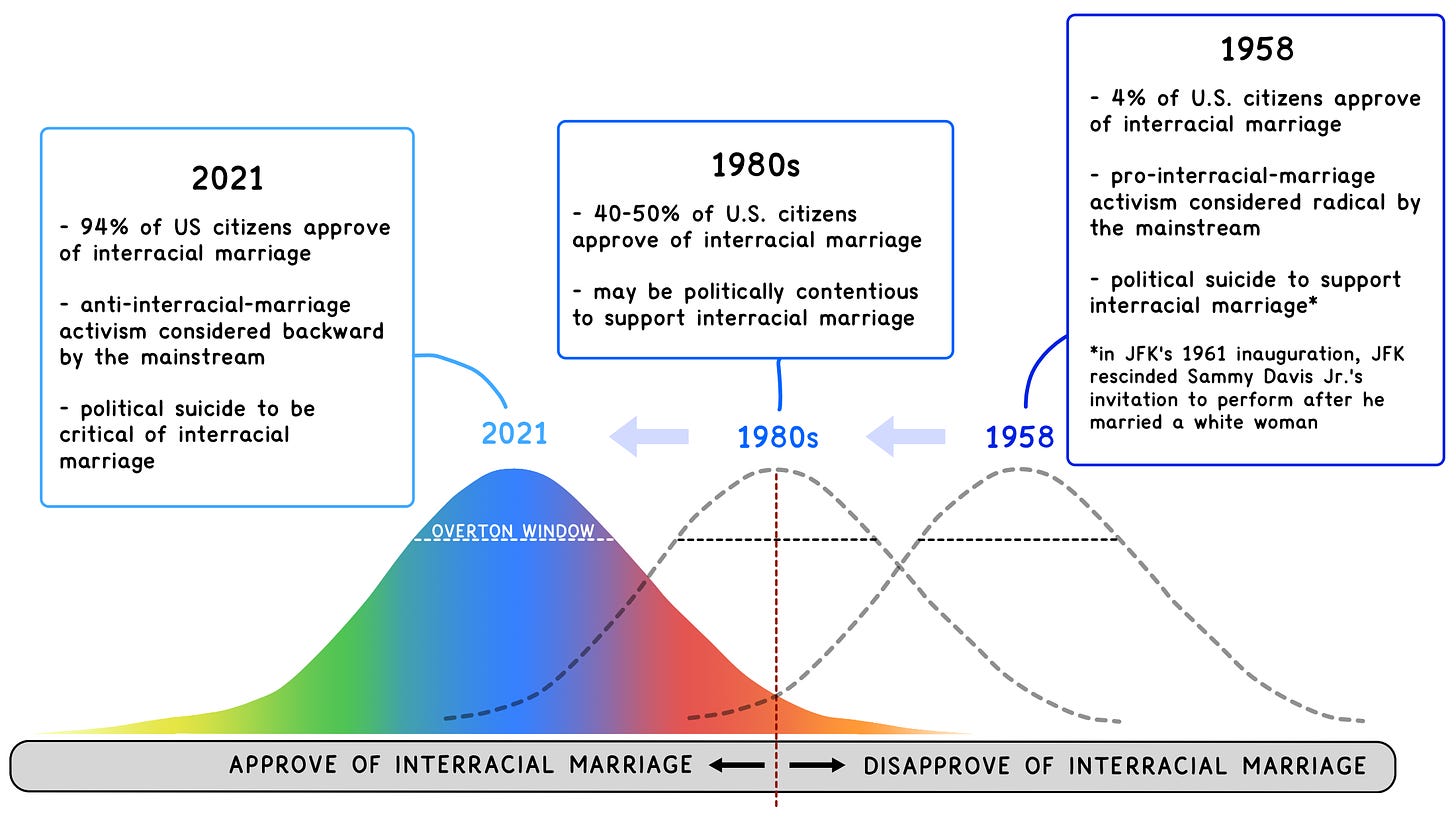

In 1958, 96% of Americans disapproved of interracial marriage.

The 4% who approved were on the far fringe:

In 1958, almost everyone in the U.S. bought into the “interracial marriage is immoral” viewpoint. Today, most of us see that fringe 4% as the wise ones, but this was anything but obvious at the time. Without free speech, that extremely unpopular viewpoint may have never been publicly expressed.

Instead, over the next half century, this small group of fringe activists shouted their unpopular views into the marketplace of ideas, igniting a mind-changing movement that spread until the change of mind had reached the center of the U.S. collective consciousness.

When the national brain changes its mind, politicians follow. The Overton window is a newish term—named after late political scientist Joseph Overton—but it’s a concept as old as democracy itself: that for any political issue at any given time, there’s a range of ideas the public will accept as politically reasonable. Positions outside of that range will be considered by most voters to be too radical or too backward to be held by a serious candidate.

It’s as if the Thought Pile is filled up to a point with water, and politicians who venture beyond the Overton window will drown.

As the national brain’s views evolve and the Thought Pile oozes its way along the Idea Spectrum, the Overton window is carried with it. When this happens, politicians have no choice but to adapt to the times or lose relevance. We can see this in the history of interracial marriage:

While most political squabbling happens within the Overton window, big picture change is driven by a second set of battles, over exactly where the edges of the window lie. If promoting Policy A would mean political suicide, it isn’t even eligible for debate. If its proponents want their chance to duke it out in the political ring, they first have to figure out how to shake that stigma.

We can see this in the history of gay rights in the U.S.

In his book Kindly Inquisitors, author and activist Jonathan Rauch describes what it was like to be gay in the U.S. in 1960:

Gay Americans were forbidden to work for the government; forbidden to obtain security clearances; forbidden to serve in the military. They were arrested for making love, even in their own homes; beaten and killed on the streets; entrapped and arrested by the police for sport; fired from their jobs. They were joked about, demeaned, and bullied as a matter of course; forced to live by a code of secrecy and lies, on pain of opprobrium and unemployment; witchhunted by anti-Communists, Christians, and any politician or preacher who needed a scapegoat; condemned as evil by moralists and as sick by scientists; portrayed as sinister and simpering by Hollywood; perhaps worst of all, rejected and condemned, at the most vulnerable time of life, by their own parents.

In a dictatorship, gay rights advocacy, considered deeply offensive to most people in 1960, would probably have been censored. But in a country that protected free speech, Rauch talks about how things changed:

In ones and twos at first, then in streams and eventually cascades, gays talked. They argued. They explained. They showed. They confronted. . . . As gay people stepped forward, liberal science engaged. The old anti-gay dogmas came under critical scrutiny as never before. “Homosexuals molest and recruit children”; “homosexuals cannot be happy”; “homosexuals are really heterosexuals”; “homosexuality is unknown in nature”: The canards collapsed with astonishing speed.

What took place was not just empirical learning but also moral learning. How can it be wicked to love? . . . How can it be compassionate to reject your own children? How can it be kind to harass and taunt? . . . Gay people were asking straight people to test their values against logic, against compassion, against life. Gradually, then rapidly, the criticism had its effect. You cannot be gay in America today and doubt that moral learning is real and that the open society fosters it.

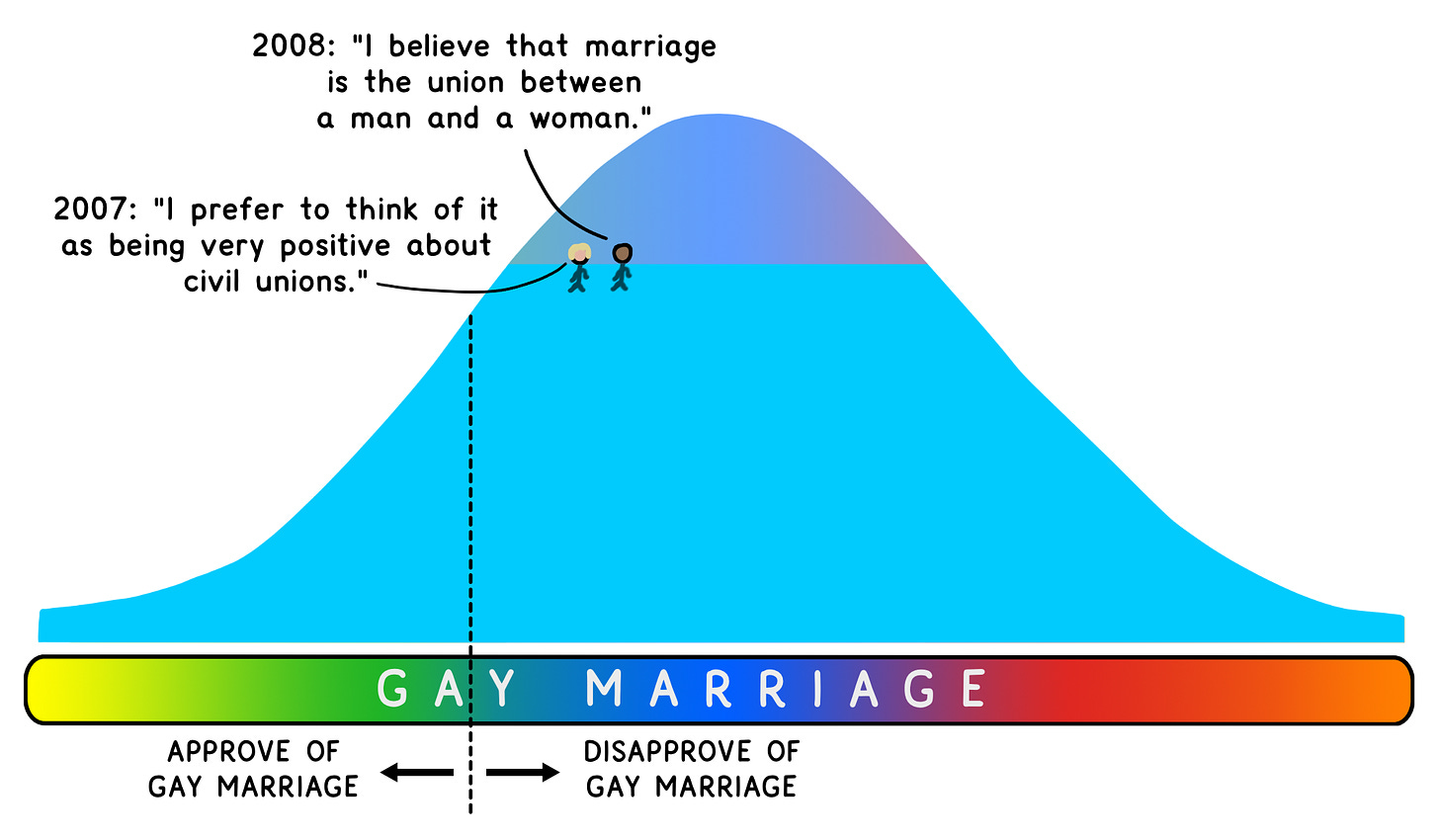

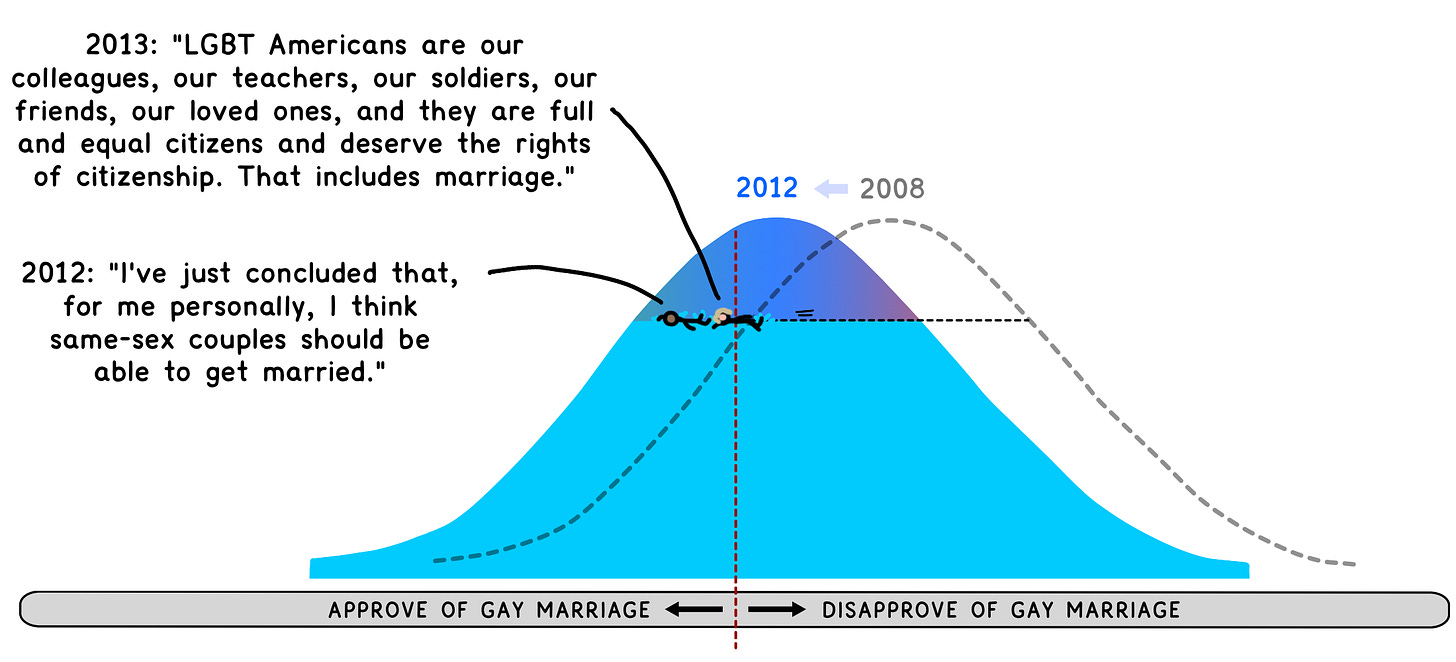

By 2008, the U.S. brain had given homosexuality a lot of reflection, and it had changed its mind considerably on the topic. But it hadn’t quite changed its mind on gay marriage yet. Most likely sensing that the pro-gay marriage stance was still below political sea level, Democratic presidential candidates Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton played it safe:

But a mind-changing movement had caught fire and the national Thought Pile was on the move. Only four years later, things had shifted. And suddenly, Obama and Clinton’s views on gay marriage had “evolved”:

The Supreme Court had undergone the same “change of heart,” and in 2015, they made it mandatory for states to recognize gay marriage.

Oppression has been a regular feature of human societies since the dawn of time, and for most of history, the primary tool to fight oppression has been violence. Free speech offers a better way. The rich are protected and empowered by their money, the elite by their connections, the majority by their vote, while minority views often end up left out. But free speech gives the powerless a voice—the ability to spark a mind-changing movement that gains so much momentum, it moves our beliefs and our cultural norms, which in turn moves the Overton window, which moves policy, and then law.

Throughout American history, free speech has been much more than protection against tyranny. It’s been the country’s brain, its compass, and its conscience.

Of course, a country like America isn’t quite as simple as I’ve presented it here.

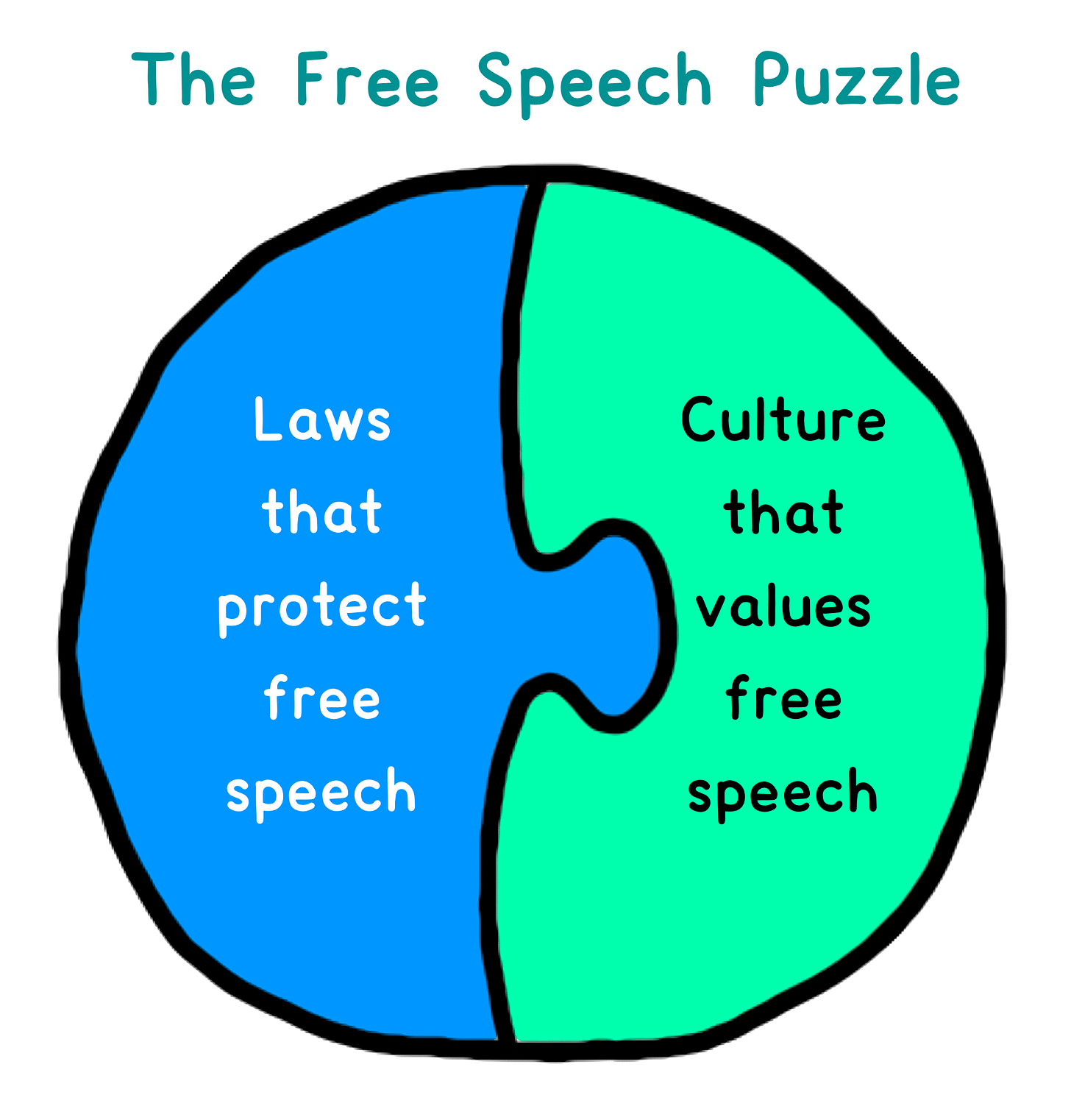

While all Americans live in a free speech country, not all Americans enjoy the full benefits of free speech. Laws like the First Amendment make free speech possible, but only within the right culture does the freedom come to fruition. What’s needed is an environment where open discourse is “how we do things here.”

In echo chamber cultures—where harsh social penalties are imposed for saying the wrong thing—freedom of speech all but vanishes, along with the presence of the marketplace of ideas.

In countries like the U.S., you’re so free that you’re free to be unfree, if you so choose. Echo chambers are like mini-dictatorships inside a larger free speech zone—a place where the culture is playing the role of King Mustache.

Political echo chambers are like frozen spots in the giant national brain—places where the flow of thinking isn’t driven by open discourse but by allegiance to certain political narratives. This distorts the marketplace, on hot political topics, into a less efficient camel shape.

The science and business worlds can advance quickly because bad ideas fail quickly. Political echo chambers allow bad ideas to live on for longer than they would in a more typical marketplace—they make the national brain less intelligent, less adaptable, less rational, and less wise.

But while these groups can slow progress, free speech means they cannot stop it. Free speech means that no one person, or group, can play King Mustache with the country by determining the narrative it believes. The U.S. is still driven by a narrative, but that narrative is ultimately written, and continually edited, by the American people.

At least that’s how it normally works. In our modern age of hypercharged political tribalism, this system is under strain. Across the political spectrum, groups that don’t represent mainstream thought have, in recent years, become unusually powerful—powerful enough to threaten the working order of the national communal brain.

Follow Tim Urban on Twitter @waitbutwhy, or sign up for the Wait But Why newsletter. And if you believe in independent journalism, become a Free Press subscriber today:

I love the analogy to the dead king and his tyrannical successor. How long before any criticism of the senile imbecile who rules over us is criminalized? The author writes "The king’s open challenge to the free speech tradition was a pivotal moment of truth in Hypothetica. Would the guards and citizens stand up for that tradition or give in to the king?"

We already know the answer to that. The FBI is all in on censorship and oppression. Would our local cops join in or stand with us? If this trend continues it won't be long before the Second Amendment is put to the test. And yes, liberty is worth fighting and dying for.

Our government is corrupt. Our populace is stupid and intellectually lazy, in general. There is a cabal with essentially unlimited money which seemingly controls and has controlled our government for a very long time. These are enormous problems, with no obvious solutions.

So my own solution for a very long time has been to speak what I think I know as clearly as I can, and more often than I can rationally justify. And my reasoning is simple: if everyone is silenced by fear, then speaking up, and hopefully saying either what people were thinking silently, or saying something new they find they agree with, is always potentially a positive and useful thing.

I'm not going to type the stories out this morning, but I have seen GroupThink in action many times. People become idiots in groups, when everyone is looking to someone else to speak up, make a decision, and/or do something. Be the one who acts. Be the one who decides. No one is going to save you if you are not willing to save yourself.