The Free Press

Two decades ago, the dawn of social media and the increasing ubiquity of smartphones catalyzed a fundamental shift in how human beings relate to each other. It wasn’t all bad: At their best, these new technologies fostered connection, communication, and creativity on an unprecedented global scale. But they also rendered visible an entire category of expression that was once kept private—the kind of thing we used to say only in the company of intimate friends or secretly scrawl in the pages of a diary. To scroll Twitter or Facebook is to literally read other people’s minds—or at least the closest we’ve been to doing this in the several thousand years of human history.

And yet: Instead of ushering in a golden age of human understanding, the transparency of social media has rendered us ever more anxious, more unhappy, more suspicious. The more time we spent on social media, mainlining the thoughts that used to live in the impenetrable darkness of other people’s minds, the more we were consumed by a paradoxical fear of all the secret terrible things they must be thinking and not saying. And what we do know, we’re tormented by—because with knowledge comes the sense, however misguided, of obligation.

It's not hard to understand how we talked ourselves into the phenomenon known as cancel culture, spearheaded by an extremely online authoritarian cohort that is utterly convinced not just of its own righteousness, but of its responsibility to police and punish. Today we are a nation of control freaks, aiming our personal technology like weapons at whatever distracts or discomfits us. Our primary response to any negative interaction is to record it for public consumption; we dig like loathsome little moles through the social media history of friends and strangers alike in search of something cancellation-worthy, or better yet, a fireable offense.

But even as the delusion that we could and should be micromanaging other people’s lives spread like a social wildfire, a sense persisted that we had stumbled into dangerous territory, that we needed someone to help us navigate this brave new world of hyperconnectedness. At first, a cottage industry of extremely online gurus emerged who mainly served the cancel culture status quo, instructing their followers in various controlling, punitive behaviors under the guise of “self-care.” It gave rise to a world where family estrangements are increasingly common, where normal dating disappointments are pathologized, and where every relationship is conducted through an impenetrable layer of therapyspeak that makes vulnerability nigh impossible.

But there are also people who want to pull us out of the death spiral of knowing much too much about everyone else, and this is where Mel Robbins comes in.

You might not know Mel Robbins’s name, but you’ve probably seen her around the internet—sporting brilliant blonde hair and thick black Buddy Holly glasses—or heard her coming out of your earbuds, delivering no-nonsense, and often profanity-laden, pronouncements about how to achieve life fulfillment in a tuneless tenor voice. Robbins boasts over 20 million followers across Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and YouTube, has the No. 1 ranked podcast on Apple, and has written five books, three of them New York Times bestsellers. Her latest one, currently in its 16th week as the No. 1 entry on the NYT Advice, How-To & Miscellaneous list, is a highlight of airport bookstore self-help sections everywhere, so popular that it gets its own little stand. More on that in a moment.

Clearly, Robbins is very, very good at giving people what they want. She test-drives her insights in 15-to-60-second videos on TikTok, to see which of them spark engagement. The most viral ones become podcast segments, while the most popular of those might eventually make their way into print; her first bestselling book, The Five Second Rule, started with a megaviral TED talk she gave in 2011 called “How to Stop Screwing Yourself Over.” But while her strategy for content creation is enviable, her real gift is being deeply attuned to what troubles the psyches of her mostly female, digital native audience—and her new book is a direct challenge to our era of collective control freakiness, in the form of a two-word mantra that provides part of the title:

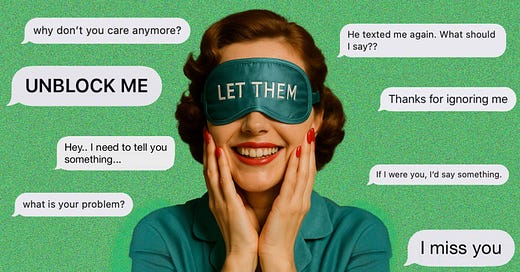

Let Them.

The book is “a step-by-step guide on how to stop letting other people's opinions, drama, and judgment impact your life.” Like Robbins’s other published works, this one began with a viral moment on social media: “I just heard about this thing called the “Let Them Theory” and holy crap… I absolutely LOVE this!!!!” she posted on Instagram in 2023. “Stop wasting energy on trying to get other people to meet YOUR expectations. Just LET THEM show you who they truly are.” That reel garnered almost 1.5 million likes, while a similar post on Robbins’s TikTok collected more than 20 million.

In the book, Robbins describes how she came up with the Let Them theory after first awakening to the truth of how often she herself was trying, frustratingly and fruitlessly, to micromanage other people’s lives. Her epiphany, she says, came on a rainy spring evening, as her son and his friends were making last-minute plans for prom night. While the kids discussed grabbing dinner at a taco bar, Robbins fretted and hovered, second-guessed and criticized. The restaurant was too small, the vibe too casual, the weather too rainy, and this was when Robbins’s daughter, exasperated, stepped in: “Mom! If they want to go to a taco bar, let them.”

Though the Let Them theory may be particularly useful for parents of the helicopter variety, its applications (per Robbins) are myriad. The coworker who doesn't pull his weight; the parents who never come to visit even as they complain all the while that they never see you; the friend who keeps going back to her dirtbag ex—all beyond the limits of your influence, all part of the titular them who must be let, and left, to their own devices. And the energy you once dedicated to steering everyone else's life? Use it to worry about the one thing you can control: yourself.

At the risk of stating the obvious, the ideological underpinnings of this idea are extremely not-new. It was roughly 300 BCE when the ancient Athenians first workshopped the philosophy of stoicism, with its emphasis on distinguishing the things within our sphere of influence from the things we cannot control; since 1941, Alcoholics Anonymous has been opening its meetings with a similar sentiment in the form of the Serenity Prayer.

As such, it’s easy to criticize Robbins for being derivative, bogarting a sentiment expressed best by Epictetus almost two thousand years ago, and passing it off as her own for a semiliterate audience of TikTok wine moms. But this would be unfair: As with all motivational speakers, the secret of Robbins’s success isn’t in what she says. It’s how she says it, and to whom; it’s the ability to interpret banal and ancient platitudes in a way that contemporary audiences find novel and inspiring—and in a medium they can consume while they fold the laundry or chauffeur their kids to soccer practice. Robbins’s followers describe her advice as life-changing; a not insignificant number are now sporting “Let Them” forearm tattoos.

And while this may be an extreme reaction, it doesn’t change the fact that “Let Them” is undeniably good advice, repackaged for a culture that pretty desperately needs to hear it. When we whip up shaming mobs against some random person who said something maladjusted on TikTok; when we shriek over the cultural appropriation of some garment or foodstuff or hairstyle; when we estrange ourselves from our family members over voting habits or vaccines; when an Oscar-nominated actor instructs his semi-pro surfer girlfriend not to post swimsuit photos on her Instagram because doing so violates his “boundaries”—what do all these things have in common if not a pathological inability to let people think, speak, act, and live as they please?

Perhaps the greatest problem with the Let Them theory is that it doesn’t go hard enough—which is to say, it doesn’t do anything to undermine its prospective practitioners’ unwavering belief in their own moral superiority, even as it encourages them to relinquish control. The thing about Let Them, at least as Robbins describes it, is that the letting is often treated like an act of magnanimity rather than one of acceptance: The object of “let” is invariably doing something ill-considered, while the person doing the letting invariably knows better. In other words, it does nothing to address the toxic certainty of the digital-era control freak that everyone around him is an idiot, and he alone knows what needs to be done.

Although Let Them theory may present itself all at once as a huge challenge, a vital corrective, and a wildly radical idea, it cannot cure what ails us culturally. Individual readers may implement this concept in their individual relationships and find some level of peace and success, but they do so against the backdrop of countervailing cultural forces that show no sign of abating anytime soon. It’s depressingly easy to imagine, for instance, a scenario in which a mom inspired by Robbins decides to let her 12-year-old daughter walk the half mile to a friend's house even though it looks like rain—only to have Child Protective Services called on her by a neighbor who thinks this is wildly irresponsible. It’s a problem of mistrust, and intolerance, but more than that: It is a problem born of the sense, so endemic among American society’s self-appointed hall monitors, that we both can and should control other people’s behavior, because we are definitely right and they are definitely morons.

Which is to say, Let Them may be a good start. A good end would be a full renaissance for the exquisite art of minding one’s own beeswax.

Don’t miss Kat’s previous essay for The Free Press, about a much-hyped new show: “In ‘Dying for Sex,’ Men Are Eternally Disappointing.”

And for more on how cancel culture took over America, read the excerpt we published from TGIF Queen Nellie Bowles’s book, “The Day I Stopped Canceling People.”