The Free Press

In October of last year, Free Press reporter Francesca Block came across a fascinating tip in her inbox. It told the story of Allan Kassenoff and Catherine Youssef, a couple of New York City litigators who married in 2006. It was a tempestuous union, which resulted in three daughters, and ended with a series of terrible abuse allegations. Allan finally filed for divorce in May 2019, triggering a brutal custody battle that remains infamous in the courts of New York. It was still ongoing when, just over a year ago, Allan received a horrifying email—Catherine had traveled to Switzerland where she would die by assisted suicide.

But death did not part the Kassenoffs.

When Francesca started digging into their story, she found that nothing was as it seemed. To get to the truth, she has spent more than eight months speaking to dozens of people and reading hundreds of documents. This is the longest piece we’ve ever published, and it’s well worth your time. Because it isn’t just a story about one family’s ugly domestic dispute, though that story is a wild one. It’s equally a story about how social media can distort our perceptions, reflecting complicated human beings in a funhouse mirror that bears little relationship to who we really are. —The Editors

I. ‘The Video Footage Doesn’t Lie’: The Case Against Allan

This is a story that ends with my own assisted death in Switzerland.

That is how the suicide note began.

Allan Kassenoff was standing in the driveway of his Westchester home on Saturday, May 27, 2023, when he read it. His wife, Catherine, had emailed it to dozens of people—including judges, attorneys, journalists, police, friends, and even staff at Allan’s law firm, Greenberg Traurig—but she hadn’t sent it to her husband. A colleague had forwarded it to him.

Allan and Catherine had spent the previous four years fighting in court over the custody of their three young daughters. After millions of dollars, and over 3,000 court filings, the divorce still hadn’t been finalized.

In four single-spaced pages, the email detailed how Allan had been an abusive husband who had manipulated the corrupt court system into cutting off Catherine’s parental rights. She accused him of “ruining the lives of my children, me,” and so many other “parents (mostly mothers) who have tried to stand up against abuse.”

“Perhaps if I had not been re-diagnosed with cancer I could have lasted in this fight longer,” she wrote, disclosing a recurrence not even her closest friends had known about, and which Allan told me he doesn’t believe was real. “But I do not have the strength to go forward,” she concluded.

Catherine also embedded a Dropbox link that included hundreds of court documents, police reports, her children’s therapy records, and videos of her husband yelling—evidence that showed, she wrote, “exactly how abusive Allan Kassenoff is.”

While reading Catherine’s suicide note, Allan started to cry, he told me. “I felt bad for her,” he said. But he also admits he felt relieved. According to him, his wife was the abusive one, and had “made my life a living hell for so long.”

But while Catherine’s story may have ended that day, Allan’s torment had only just begun. In her suicide note, Catherine told readers, “Don’t let my death be in vain.” And whether she knew it or not, there were plenty of people willing to avenge her.

Then a successful patent litigator—representing big-name companies from Pfizer to Samsung and making nearly a million dollars a year—Allan was working at his law firm’s office in White Plains the following Wednesday, May 31, when his phone started ringing. He didn’t recognize the number, but picked up, and the person at the other end of the line started cursing at him.

“As soon as I hang up,” he told me, “it’s ringing again.”

He was bombarded by strangers’ voices, he told me, calling him an “asshole,” or claiming he “killed his wife,” or telling him he should “lose his kids.”

Within hours, all his email inboxes had also started to fill up with death threats from people he didn’t know. “Burn in hell,” read the subject line of an email sent to his work address. “I hope you die,” the stranger wrote. He was also getting messages on Facebook: “Go kill yourself,” “Die slow and painfully,” “Coming for you.” One person tracked down his home address and sent him a bottle of red paint—including a note: “I hope the color red haunts you for the rest of your life. From Catherine.”

Whoever it was did the same thing for five other colors: orange, yellow, blue, purple, and green.

Then, one of his daughters told him that an account on TikTok had begun posting Catherine’s videos of Allan. The account, which then had over 2 million followers, is run by Robbie Harvey, a 41-year-old digital creator living in Pensacola, Florida, who presents himself, in his TikTok bio, as a “citizen journalist.” A self-proclaimed recovering “narcissist” and “former bad husband,” Harvey’s page was dedicated to “speaking up for women.”

He started posting about Catherine four days after her death.

“This is quite possibly one of the most heartbreaking videos that I have ever created,” Harvey says in his first TikTok about the Kassenoff case. He’s sitting in a soft-lit room wearing a gray t-shirt, before his lips curl inward, almost quivering. “It does not have a happy ending.”

Harvey then plays one of the videos that Catherine included in the Dropbox link she sent out the day she died. (It’s not clear how he came by the footage. Harvey declined to comment for this story.) It shows Allan storming around the house, shouting at his wife, repeatedly yelling “Shut up.” You can hear kids screaming in the background.

In another video Harvey shares, Allan calls Catherine a “fat loser.”

“What did you call me?” she says.

When he repeats the insult, she instructs him to say it “one more time.” He does.

Then, Harvey takes out his phone and reads from Catherine’s suicide note, which she posted to Facebook, as solemn piano notes begin in the background.

Seeing Harvey’s post, Allan realized why he’d been getting death threats. As so often happens on social media, the TikToker had told a compelling story of good and evil, then watched it go viral: Harvey’s original post has since been deleted, but screenshots show it received at least 23.1 million views; Harvey re-uploaded it on June 13, 2023, and this version has since racked up 11.7 million views, 1.4 million likes, and over 14 thousand comments.

“Allan Kassenoff should be arrested for abuse,” reads one.

“Justice for Catherine,” many others declare.

“We will be her voice,” one user promises. “We won’t let him get away with this.”

But Allan insists the reality of his marriage was far more complicated than the TikTok narrative makes out. He told me he felt “embarrassed” about the videos of him screaming and says: “I regret my reactions to her behavior—especially when the children were present.”

But the footage was, he said, taken out of context: “What people don’t understand is what happened before that and what happened every other day.” His wife, he says, pushed him to the edge.

One of his daughters also had objections to Harvey’s version of events. The day after the TikToker first posted about the Kassenoffs, their middle child, then 12, sent him three messages in a row:

“Why are you posting videos about my dad?? Stop getting involved.”

“You don’t even know the true story.”

“You don’t know anything.”

In response, Harvey made another TikTok post, which included screenshots of the messages—and accused Allan of sending them from his daughter’s account. (This daughter confirmed to me that she sent the messages herself.)

In the video, Harvey breaks the fourth wall: “Allan, I know you’re watching me,” he says to the camera, before posting the screenshot: “Is this you?”

In the weeks that followed, Harvey posted almost daily about Allan—making nearly 40 TikToks that often reuse the same pieces of video footage. Some have gained over 10 million views. “I know there are many sides to a story,” Harvey says in one, pausing slightly before adding: “The video footage doesn’t lie. That monster has possession of these children, so I’m going to keep talking about it.”

That video has gained 1.6 million likes.

In the month after Catherine’s death, Harvey’s account grew by half a million followers—followers that Harvey urged to take action. In a video that has since been deleted—but which Allan saved and says was posted on June 8, 2023—Harvey says to the camera: “Allan Kassenoff is a shareholder at this law firm,” before posting the logo of Greenberg Traurig. “And since this law firm has not done the right thing and fired Allan Kassenoff. . . I figured it’s time to get their attention.”

He then identifies Allan’s biggest client, Samsung, before saying: “If there was only a way for millions of people to get the attention of Samsung and let them know who represents them.”

He then cocks his head as Samsung’s TikTok handle appears onscreen.

The same day, Samsung started getting messages like this reply to a tweet from its U.S. division’s official account: “You support domestic violence. Boycott Samsung. Allen [sic] Kassenoff needs to go to jail!”

And, in the early afternoon, Greenberg Traurig received an email with the subject line “Allan Kassenoff.”

“You should definitely fire that weak ass man,” it read. “Have you not seen what the internet can do? You all are definitely losing all your costumers [sic] and hopefully lose Samsung.”

The day after Harvey posted about Allan’s job, Allan was at the gym when, he says, his boss at Greenberg texted, “Can we please talk?” Within a few hours, Allan said he was presented with an ultimatum: resign with a severance package or get fired. He had two days to decide.

Allan told me he approached an employment attorney, hoping to fight for his job, but was told the nature of his contract wouldn’t allow it. All he could do was take the package and leave quietly, he said. “I had no choice; I really had no choice.” (He said he did manage to negotiate an extra three months of severance.)

I spoke to two Greenberg employees who had both worked with Allan for over a decade. (Neither wanted to be named.) One called it a “very difficult situation,” and the other said it wasn’t “an easy decision” to let him go, but when clients are targeted by such attacks, it is “disruptive to the business.” But, one of the employees added, “there were a lot of people who felt very bad for him.” (Greenberg itself did not respond to a request for comment.)

“I personally think that the TikToker appeared to be on a mission to destroy Allan without regard for the completeness of the facts,” the first individual told me. “I think many of the articles or publications that described what happened picked up on the easy, low-hanging, salacious fruit.”

With Allan’s resignation, the story of the Kassenoffs received tabloid attention—and the headlines were devastating. The Daily Mail emphasized Catherine’s claim that she had been “driven to assisted suicide” by the combination of cancer and Allan’s “domestic abuse,” trumpeting: “Husband. . . QUITS law firm after probe by his bosses.” “Attorney out of job after. . . scathing claims go public,” declared the New York Post. Both stories embedded Robbie Harvey’s TikToks.

On June 11, 2023, the day Allan resigned, Harvey posted a video where he gave the names and photos of people involved in the divorce case who Catherine perceived to have wronged her—including the lawyer representing their children, the psychologist who recommended Allan have full custody, and one of the children’s therapists.

Harvey alleges in the video that all of them “colluded with each other to make sure Catherine Kassenoff could not see her children ever again.”

The next day, in response to Allan’s resignation, Harvey made another video that has since been deleted: “There’s still a lot of people out there that need to answer for the decisions that they’ve made.”

“Your actions have consequences,” he said. “And I’m going to make sure those consequences come.”

II. ‘When It Was Bad, It Was Beyond Belief’: The Marriage

Catherine Youssef met Allan Kassenoff in New York City in 2005. He was an upstart, 33-year-old patent litigator; she was an associate at his law firm, four years his senior, and had already served as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York.

They started dating after they’d known each other a few months, and Allan says their relationship was a “roller coaster” from the beginning.

“When it was good it was great,” says Allan, over the phone. “But when it was bad, it was beyond belief.”

He’s reluctant to talk about the good times, or what he used to like about Catherine, but he will say: “She was, like, no-nonsense. Like, ‘I don’t take crap from people.’ ”

“It was an attractive quality,” he adds.

When I ask him what he and his wife had in common, he replies bluntly: “We were both litigators.”

The couple got engaged after a year and planned to have a small wedding in November 2006. They couldn’t agree on a venue: Allan says he proposed a kosher restaurant to accommodate his Orthodox Jewish family, but Catherine refused on the grounds that her family, who are Egyptian Coptic Christians, would object. (Catherine converted to Judaism to marry Allan.) In the end, the couple eloped in Puerto Rico.

I reached out to Catherine’s mother and two brothers for comment—her father has passed away—but none of them responded.

After they got married, Catherine wanted kids “ASAP,” Allan told me; she wanted to do IVF straight away, he said, before they’d even started trying naturally. He wanted to have kids, but he also wanted to at least try to get pregnant without medical intervention, given the expense of IVF—but Allan caved, he said, because Catherine, who was nearing 40, was so adamant. Allan says they underwent several rounds of IVF, estimating that in total the couple spent upward of $200,000 on fertility treatments.

Then, less than two years into their marriage, Catherine was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of breast cancer and received treatment. According to her therapy records, which Catherine shared with her suicide note, she later told a therapist that Allan “showed that he was not good at handling stress” during this time.

While she recovered, the Kassenoffs decided to adopt. They contacted an adoption attorney, who matched them with a woman in Florida who was pregnant but unable to look after a baby; in July 2009, the Kassenoffs became parents to Ally, who was delivered to them straight from the hospital where she was born.

Soon thereafter, Allan says Catherine wanted to try IVF again—and threatened to do it “with or without me.”

He went along with it, but told me he was “nervous, because of how bad our relationship was.” He didn’t think bringing another child into the family was “the best thing in the world.”

This time, the IVF worked: less than a year after she adopted Ally, Catherine got pregnant. The Kassenoffs’ second daughter, Charley, was born in February 2011—and was quickly followed by a third, JoJo, in August 2013.

Allan says he was happy to be a father. But he wasn’t home a lot. When the kids were babies, he was working long hours, consistently getting back around nine or 10 at night.

Meanwhile, in July 2014, less than a year after JoJo’s birth, Catherine was fired from her job as head of litigation at Boehringer Ingelheim, a pharmaceutical company. She immediately went after the company, accusing it, through an attorney, of discriminating against her for being a caregiver. In the course of the dispute, Boehringer Ingelheim took the position that Catherine was let go because, among other reasons, she made “bad and illogical decisions.”

Later, Catherine claimed in court documents that she had “left” this job in order to “serve as the primary caregiver.”

But by March 2015 she was employed again, working for Governor Andrew Cuomo as a Special Counsel for Ethics, Risk, and Compliance.

With two career-oriented parents, nannies were a constant during the girls’ childhoods—some staying a year or so, others lasting just a few months. Of the four I spoke to, all said the Kassenoff house was a tense place to be; also, all but one told me that Catherine showed a strong favoritism toward her two youngest daughters—at the expense of Ally, her adopted one.

Kim Hull was hired as a live-in nanny in 2009, when Ally was just an infant—and she told me several disturbing stories about Catherine. Once, she said, Catherine instructed her to keep the baby awake all day by dripping water on her head, so that she would sleep through the night. Hull said she refused, worrying that it bordered on “abuse.”

Hull also said she found marks on the baby’s back that looked like they’d been caused by fingernails digging into skin—which concerned her so much she took Ally to the doctor.

Hull never reported Catherine, out of multiple fears: “I’ll lose my job. I’ll be investigated. I’ll never get a job again. And I don’t have proof that she did it.”

“She terrified me,” Hull said.

Celine Dublanchet, who became the Kassenoffs’ au pair in October 2016, also made disturbing allegations about Catherine. According to court documents, Dublanchet said Catherine once locked Ally, then 7, in the basement by herself for two hours as a punishment, and on another occasion made Ally go outside alone after dark to “clean the garden” in the middle of winter.

Dublanchet claimed that Ally slept on a mattress on the floor in her room, while the other two children slept in Catherine’s bed every night. Every morning, she told me, Ally had to make her mother’s bed.

“Ally was Cinderella,” Dublanchet later wrote to the court, “her two sisters Anastasia and Drizella, and Catherine the horrible stepmother.”

When I asked Dublanchet what she thought of Allan, she called him “very nice.” And though she acknowledged that “he could be very angry,” she quickly added that Catherine “pushed him to his emotional limits.”

“She wanted the girls to see their father be so angry,” Dublanchet said. “She did it on purpose, to have the children on her side.”

After six months, Dublanchet’s visa expired, and she had to go back home to France. “When I left the house,” she said, “I wanted to take Ally with me because I felt so sad and bad for her.”

Another nanny, Mylene Gry, lived in the Kassenoffs’ home from 2015 to 2016. When I spoke to her, she said she saw Catherine “scream at Ally for almost 10 minutes after she misbehaved—she said things such as ‘You will never have friends’ and ‘You will never succeed in life or get married and have your own kids.’ ”

“What I witnessed in my 13 months working for the Kassenoffs has troubled me to this day,” Gry later wrote to the court in June 2019, when the couple was fighting for custody of the children. “I believe Catherine is a mentally ill and abusive person.”

Mylene also told me that in March 2018, a former au pair had posted in a Facebook group for French nannies in the U.S.: “Careful to all au pairs who are looking for a family, I won’t advise you to work for the Kassenoff family, the mother is a psychopath.”

Robbie Harvey, of course, told a different story in his TikToks—and so did the friends of Catherine I spoke to. Wayne Baker, a lawyer now living in New Mexico who Catherine met in 1999 through work, told me Catherine did not abuse Ally but merely disciplined her for misbehaving.

“She was the parent that was home all the time. She was the one dealing with it. Allan was rarely there, and when he came home, he would say, ‘Oh, why are you treating Ally like that?’ ”

Allan admitted to me that he often volunteered to go on long, international work trips, to avoid “the amount of stress in the environment at home.”

He didn’t realize how badly Catherine was treating Ally, he claimed, though he was aware that his wife treated their adopted daughter differently from their other children.

When I ask him why he didn’t intervene more to protect his daughter, he grows uneasy, often pivoting away from my questions. He claims he held off on filing for divorce because he feared Catherine would get custody, which would only make life worse for Ally.

But he also admits that his frequent absences may have enabled the abuse. “Maybe I wasn’t doing the best job in the world because I had a job,” he says. “But I did the best I could.”

When he was home, he made everything worse, according to a friend of Catherine’s who didn’t want to be named. (She feared Allan might sue her.) This woman, who Catherine had known for decades, says that when she was on the phone with her, she often heard Allan yelling in the background. Allan was a “monster,” she says, who Catherine “had to get away from.”

Catherine told friends—and later, the court—that it wasn’t just verbal abuse. Between 2016 and 2019, she sought urgent medical care at least three times for injuries she alleged were caused by her husband. Hospital records, which Catherine submitted to the court during the custody battle, show that she told doctors Allan had picked her up “and slammed” her to the ground, that he “threw her across the room and she hit her right arm and head on [an] ottoman,” and that he “threw a mixture of grass and sod” at her eye. Her medical records also show that doctors noted redness—and in one case a couple of abrasions—but no significant injuries.

After a trip to the hospital on May 11, 2019, Catherine texted a friend: “If I had a mark or a bruise or something, it would be easy.”

“You don’t need a bruise to divorce him,” the friend texted back.

“Just to get full custody,” Catherine replied.

Allan submitted screenshots of these messages to the court. According to him, Catherine was crafting a narrative in which she was an innocent victim, and he was an evil husband—similar to the narrative that ended up going viral on TikTok.

Allan denies all allegations of abuse. “She used to call the police on a weekly basis,” he says, but they never pressed charges. “Each time it was more nonsensical than the time before. But she was trying to build a case. Do you see what I mean? She’s a lawyer. She’s very conniving and scheming.”

On May 15, 2019—mere days after Catherine sent the text that began, “If I had a mark or a bruise”—Allan says his eldest daughter went to school and told her teachers that her dad had kicked her a couple of days earlier. The school immediately launched a Child Protective Services investigation.

Allan had already left for an overnight work trip to Long Island. He didn’t get home until 10 p.m. the next day, after everyone in the house had already gone to bed. In the morning, he wanted to ask Ally why she had made the accusation—which he insisted was completely false—but he said Catherine stopped him. He went to work at Greenberg’s offices in New York City, and by the time he returned after dark, the house was empty. He says he immediately thought that Catherine “may have kidnapped the kids.” By this point he was in touch with a divorce attorney, Gus Dimopoulos, who advised him to stay home and wait.

The next morning, Saturday, May 18, Allan woke to an email from Catherine’s friend Wayne Baker, informing him that she had obtained an order of protection, barring Allan from contacting her or the kids. Allan says he believes the entire story about “the kick” was fabricated by Catherine, and she told Ally exactly what to say to school officials—all so that she could get custody of the kids.

When I asked Ally—now almost 15—about it, she supported Allan’s version of events, saying her dad had not kicked her; what she’d said to the school wasn’t true. “My mom told me to, like, always say bad stuff about my dad,” she told me.

Claiming his wife was abusive, Allan was the one who officially filed for divorce, on May 24, 2019. A couple of weeks later, he submitted to the court recordings of Catherine berating Ally, calling her a “moron” and a “complete idiot,” yelling at her for stealing a chocolate bar from Catherine’s bedroom, telling her “You will go to jail if you keep this up.”

It’s the kind of footage that could go viral on TikTok.

Allan also wrote an affidavit, in which he claimed his wife had fabricated the story of the kick. “I have come to learn in the past two weeks that Catherine has planned for divorce,” he wrote.

He added that their marriage had been “destined to fail from the beginning.”

“I am ashamed and embarrassed that I have waited this long to do this,” he wrote, “but my inaction was motivated only by what I thought was the best way to protect my daughters—that is, to remain miserably married in a constant state of lies, deceit, false accusations, and spousal abuse, so that I could do my best to protect my children from their mother.”

III. ‘Holier Than Thou’: The Battle for Custody

The Kassenoff divorce was infamous in the courts of New York. One attorney who was involved in the case, and who has worked on over 100 divorces during a 45-year career, told me it “was probably among the top two or three most contentious cases I’d ever had.”

It revolved around a brutal battle for custody. After Allan submitted the affidavit claiming their mother was abusive, a judge decided the kids’ father should temporarily have full custody. A few days later, Allan and Catherine agreed to share custody as they prepared their cases against each other—but the judge ruled she couldn’t be home alone with the kids. An approved friend or family member always had to be present.

The judge also appointed psychologist Marc Abrams—who had worked in the Westchester County courts system for over two decades—to offer a neutral assessment of the parents and recommend a custody agreement. Though the report is confidential, Abrams revealed during a July 2020 temporary custody trial that he recommended Allan have sole custody of the kids—and that he believed Catherine had an “unspecified personality disorder.”

Catherine refuted this claim. During the same trial, a psychiatrist she had been seeing on and off for a year, Dr. Anna Filova, affirmed that Catherine “does not exhibit any features or problems relating to mental health issues,” and that she was in therapy “probably related to spousal and emotional physical abuse, divorce, separation from the children.”

Catherine also submitted a letter from Katherine Klein, who had worked for the family as a nanny from March to July of 2018—and who wrote that Allan was “manipulative and cannot control his temper.” The kids, Klein wrote, “should be with their mother as much as possible, even exclusively.”

When I called her in May, Klein told me that Allan used “verbal abuse” and “emotional blackmail” against Catherine and the kids. One time, when JoJo, the youngest daughter, was sprayed by a skunk, Klein said she witnessed Allan “yelling and screaming” so much that his daughter was “physically scared” and “shaking.” (Allan denied this.)

Abrams, the psychologist, did support some claims about Allan’s bad temper. In his testimony, he criticized Allan’s “rash inappropriate yelling,” for instance. Both parents, Abrams added, “showed incredibly poor judgment in creating this kind of noxious atmosphere for the children”—he didn’t think “either one of them should necessarily be applauding themselves as being holier than thou.”

“They both,” he went on, “played a role in this violence that occurred.”

Though TikTok paints Catherine as a martyr, what the courts revealed was that she was no saint.

Ultimately, Abrams said in court, Catherine “was clearly the more powerful partner,” and displayed much more of an “aggressive, confrontational style” than Allan. Three former nannies also testified in favor of Allan.

The result of the July 2020 trial was that the judge reaffirmed Allan’s temporary full custody of the kids—and that Catherine could see them only under supervision.

Catherine continued to protest against this arrangement—right to the end of her life. In her suicide note, she wrote that “the Courts of New York State are so invested in minimizing, suppressing, and punishing valid claims of abuse” that they “imposed ‘supervision’ on me for saying that the girls were telling the truth about their father’s abuse.”

IV. ‘She Went After Everyone’: Catherine’s Revenge

Catherine used social media to fight back. A lot of her Facebook posts have been deleted, but the dozens of screenshots I’ve seen suggest that she documented every twist and turn of the custody battle—and went after anyone who disagreed with her.

One post, which Allan says Catherine made on May 14, 2021, shows that Catherine criticized the children’s attorney, Carol Most, on Facebook, writing that Most “has been actively suppressing any evidence that is detrimental” to Allan.

“She is completely aligned with his interests,” Catherine claimed.

Most denies these allegations. “The mother was trying to create a story for herself, but it just wasn’t true,” she told me.

But Catherine did ultimately get Most removed from the case in October 2022 by order of the court, after the judge found Most had made statements to the court “for no apparent reason other than to denigrate the mother.” As a result, Most was denied her fee for working on the case, which amounted to over $100,000.

“It was just what Catherine Kassenoff was about,” Most told me when I spoke to her in December 2023. “If you don’t agree with her, or do what she wants, you had to be punished.

“That was her legacy. She went after everyone.”

It wasn’t just Carol Most.

Catherine, along with two other women, filed complaints against Marc Abrams, the psychologist who recommended Allan have custody, alleging professional misconduct and inappropriate behavior toward women. Abrams denies these allegations, calling them and any others “defamatory.” After an investigation, the panel of court-approved mental health professionals removed him, meaning he could no longer provide court evaluations—a lucrative gig, with each case paying around $50,000.

“I still have my license,” Abrams told me—adding that he’s “been in the business long enough to still have a good practice”—but the damage to his reputation has caused “a tremendous amount of stress.”

Catherine celebrated his removal in an August 27, 2021 Facebook post, writing that Abrams, as well as Most, had “destroyed my family to line their own pockets.”

Then, in October 2021, Catherine sued the two youngest girls’ therapist, Susan Adler, claiming she had “cast aside her moral and ethical obligations by manipulating the children and unjustifiably recommending their removal” from her care. The case stayed open for nearly a year after Catherine’s death—with Wayne Baker, the executor of her estate, representing her interests. It finally came to an end this past May, when both parties agreed to dismiss it.

Adler has continued to work, but the accusations have weighed heavily on her. “It was one of the most horrible things of my life,” she told me when I spoke to her earlier this year, adding that her only goal had been “to protect these children as much as possible.”

“If it looked like I was taking his side over hers, I was taking the children’s side.”

While going after those she believed had wronged her, Catherine became something of an advocate for family court reform in New York—attacking a system that many agree is broken. After sharing details of her case, she often made comments like this one, from 2021: “What occurred here occurs in courtrooms all over this country, and the world.” Other women who felt victimized by the court system often commented on her posts.

Also in 2021, Catherine testified before a commission that was investigating the use of court-appointed psychologists in divorce cases, which reported its findings to Governor Kathy Hochul; at the end of the year it concluded that the process “is fraught with bias, inequity, and a statewide lack of standards, and allows for discrimination and violations of due process.”

Shortly afterward, in early 2022, Catherine helped found an organization called WeSpoke, which focuses on “speaking up on the systemic failures in Family & Matrimonial Courts across America.” She partnered with Natalie Blundell, another divorcée living in Westchester, who told me she’s worked with over 300 women who felt trapped by the family court system. Blundell says she believes it is inherently biased against mothers—painting them as “unhinged” or “unstable.”

She also points out that in places like Westchester, men tend to have more money to spend, so they get to control “the narrative” of a divorce.

“This wasn’t just Catherine’s story,” she told me. “This was happening to a lot of women in New York State.”

“Knowing her and also knowing many other cases like hers, I don’t think there’s ever, ever going to be justice,” Blundell told me.

Catherine went to extreme lengths in pursuit of what she saw as justice. When I asked Blundell about Catherine’s suicide note, she said: “I think everyone is going to interpret her email and her announcement differently.”

“I don’t believe Catherine did that to be spiteful, or to really cause harm to her girls or to Allan,” Blundell added. “I think she wanted the truth of what’s going on in these courts spread.”

V. ‘The Death Knell’: The End of the Battle

In the course of reporting this story, I found hardly a single fact that everyone agreed on, except that the drawn-out custody battle took a terrible toll on the Kassenoffs’ three girls. The Dropbox folder Catherine emailed to dozens of people the day of her death included her daughters’ therapy records, which show how much these children suffered, emotionally and sometimes physically, while their parents fought over them.

In 2022, the girls were meeting their mother once a week, supervised by a counselor, in Carmel, New York—about an hour from their home. Before and after seeing Catherine, they often waited at The Carmel Diner, across the street, where they became friendly with a waitress named Jennifer Voltz.

“I loved them to death. All of them,” says Voltz, who could still reel off their regular orders when I spoke to her in February. JoJo and Ally always ordered chicken fingers, she said, while Charley got grilled cheese and chocolate milk.

Voltz had a front row seat to how the girls’ visits with their mother affected them. “There was not one day when one of them didn’t come out in a rage, or like breaking down crying,” she says. “They just didn’t want to be around her.”

“It was honestly devastating,” she added, “as a mother myself.”

“They just wanted it to be over with, you know.”

Allan was determined that the children would never live with their mother. On March 19, 2023, he sent his wife an email: “Even if this Court awards you my last dollar, I will never stop protecting them. Until the day I die. If I lose my house, so be it. If I go bankrupt, so be it. I will do everything and anything to take care of the kids and protect them.”

“All you know is hate and vengeance,” he added.

(The Daily Mail reported on this email under the headline: “ ‘Abusive’ husband sent terrifying email to NY mom-of-three claiming he ‘will never stop.’ ”)

A month later, Catherine bought a three-bedroom house in Westchester for nearly $900,000, despite having just submitted an affidavit to the court claiming she was in “dire need of financial assistance” from Allan. The previous year, Catherine had been awarded nearly $300,000 by the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, after she claimed to have suffered “cancer-related injuries” because of the attack—and she wrote in the affidavit that she’d had to use that money to buy the home.

When I asked Wayne Baker, the executor of her estate, about the house purchase, he said it was a sign that she had hoped, right until the very end, to be reunited with her kids.

“She thought she was going to have sleepovers with the children,” Baker said. “She bought beds for them, bought backpacks, and all these little things. You could see she was just so excited about the prospect.”

But on May 2 of last year, a new court-appointed psychologist issued an incredibly thorough, over 100-page report that was so damning for Catherine, a judge suspended all access to her kids until further notice.

“That was the death knell,” said Baker. “Basically, the court said you can’t live with them. And she said, ‘Well, I can’t live without them.’ ”

VI. ‘Understandable Misery’: Catherine’s Suicide

Catherine’s plans to kill herself came as a surprise to almost everyone she knew. Several of her closest friends told me they found out through email or Facebook on the day of her death.

“I was completely shocked,” said Keri Christ, a friend she met in 2021 through WeSpoke, and who is the trustee of Catherine’s estate. She was among the dozens of recipients of the email Catherine sent on May 27, 2023. “I read the first sentence and I immediately tried to call her,” she told me. “But she was not picking up the phone.”

“I obviously didn’t know,” her psychiatrist, Dr. Stephanie Brandt, told me. “It would have been my ethical obligation to stop her.”

But in fact, Catherine’s plans had quietly been in motion for some time. One of the documents she included in the Dropbox along with her suicide note was a medical report dated April 9, 2023, and signed by Colin Brewer—a UK-based former psychiatrist in his eighties. Brewer is the author of the 2015 book, I’ll See Myself Out, Thank You, which argues that “people with terminal conditions, or poor quality of life due to illness or treatment” should “be allowed to be helped to kill themselves.”

In the medical report, Brewer confirmed that Catherine was of sound enough mind to kill herself, writing that she is “not suffering from a psychiatric illness and continues to understand the nature and purpose of [Medically Assisted Suicide].” Brewer also comments that Catherine’s death “was originally scheduled for October [2022] but was postponed twice for administrative reasons.” In other words, she had been planning to kill herself long before the courts suspended access to her children.

When I spoke to Brewer, he told me Catherine had first reached out to him at some point in mid-2022 and was already in contact with the renowned clinic in Basel, Switzerland, called Pegasos. It allows anyone—regardless of where they are from and whether they have a terminal illness—to kill themselves, as long as they are “of sound mind.”

Brewer believes Catherine got his contact details from the clinic. (Pegasos did not respond to a request for comment.)

Brewer told me he ended up writing four medical reports. Every time Catherine’s assisted suicide was rescheduled, he had to evaluate her again and issue a new one—and he also spoke to her a few days before she died.

Brewer therefore spoke to Catherine multiple times over several months. According to him, she never seemed anything but competent. “She was always very calm,” he told me, then added: “She got naturally a bit exasperated when talking about her husband.”

She was, he said, “very clear about what she wanted to do and why she wanted to do it.”

Catherine’s suicide note claimed she could have “lasted. . . longer” if she had not been “re-diagnosed with cancer.” Brewer said Catherine told him she had cancer, but when I asked whether cancer was the reason she had decided to end her life, he said: “Absolutely not.”

“It was not something that troubled her, because she wasn’t planning to be around long enough for it to cause trouble,” he told me, adding that she wasn’t seeking treatment, because of her plans to die. “She was just concerned that she had been treated abominably by her husband.”

Catherine’s case for assisted dying was “unusual,” Brewer explained, because there was “no serious psychiatric diagnosis involved.”

“Catherine was functioning extremely well,” he said, “as evidenced by her ability to get all these documents out into the world before she actually departed from it,” he added—referencing her suicide note.

He called hers an “existential assisted suicide”—which is “when people feel that they have failed to achieve something very important or that something very important is being destroyed.”

He made “no actual medical diagnosis,” he clarified; Catherine’s case was one of “understandable misery.”

Brewer was “struck off” the medical register in 2006, after the UK’s medical body found him guilty of “irresponsible prescribing practices” in treating people struggling with drug addiction. A Telegraph investigation into the case suggested that Brewer was caught in the middle of “a showdown. . . between two opposing schools of opinion about how heroin addicts should be handled.”

When I asked him about this, Brewer stated: “My dispute with medical authority arose in the context of a big row with the addiction establishment. They were determined to get back at me for making them look bloody silly.”

Pegasos does not require someone to be a registered doctor to sign off on assisted suicide, he added, “as long as you have the necessary experience and qualifications.”

Brewer spoke to Catherine again a few days before her death, issuing a final report on May 25, which he read to me over the phone. In it, he confirms that Catherine showed none of the “classic features of severe depressive illness,” and wrote that she is “looking forward to no longer having to live with a domestic situation becoming increasingly intolerable.”

“She traveled to Basel and she was comforted to meet the family of another Pegasos client,” the report goes on. “She has also made extensive arrangements for her children to learn of her death in a setting that she hopes will minimize their distress.”

If she had made such arrangements, they didn’t work. Ally told me she found out about her mother’s plans to kill herself from a Facebook post Catherine made the day of her death.

Katherine Klein, one of the Kassenoffs’ former nannies, believes she was the last person to speak to Catherine before she died. She told me that when she read Catherine’s suicide note, the morning it was sent, she called her cell phone right away.

“I kept calling and I got hold of her,” Klein told me. “It was 12:08 in the afternoon.”

“I was, like, begging her not to do it.”

“And she said, ‘I’m already here.’ ”

Catherine told Klein that the IV of chemicals that would kill her was already in her arm—but she offered one last piece of advice, from one mother to another.

“She just told me to always help my children first,” Klein said—“to never allow anyone to get between me and them.”

VII. ‘The Gospel of Me Being the Devil’: Allan’s Case Against Robbie Harvey

Sitting behind the wheel of his black SUV on a cold and dreary afternoon in Westchester in late November 2023, Allan looks resigned. His hair is graying at the sides, and he hunches toward the dash, peering through the raindrops on his windshield.

As he makes a turn, I notice he is wearing a colorful friendship bracelet on his right wrist with beads spelling out “Best Dad Ever”—a bracelet he tells me he hasn’t taken off since his youngest daughter, now 10, made it for him at camp last summer. I can’t help wondering whether he’s just wearing it because of my visit: once you’ve heard any version of the Kassenoffs’ story, it’s hard to know what to believe.

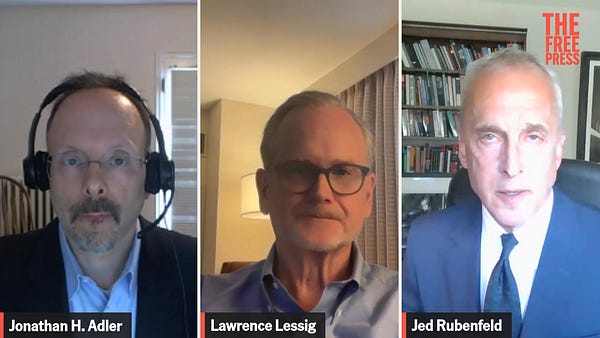

Allan parks in the driveway and walks the stone pathway to his back door. With one hand, he carries a bag of fresh bagels from a nearby deli; in the other, he holds a tattered brown accordion file folder full of legal documents. As an unemployed lawyer with endless free time outside caring for his daughters, Allan was spending his days collecting and organizing thousands of documents, working on his latest legal case—against Robbie Harvey. Last September, Allan filed a defamation lawsuit against the TikToker for $150 million to compensate for his loss of earnings and his “destroyed reputation.” On July 5, 2024, they settled the case under undisclosed terms.

On the day of the settlement, Harvey issued a nine-minute apology video. Sitting in a plaid shirt, in a dark room lit by purple LED lights, he admits that he “made some mistakes in the reporting of the story” of Catherine and Allan’s divorce.

But, he continues, he made those mistakes because “Catherine did not provide a complete record of what was happening.” And rather than seek out the other side, he admits, “I echoed exactly what Catherine said.”

Harvey said Catherine uploaded “many documents and videos. . . that she believed would support her claims.” But, he adds: “What Catherine did not do is upload all of the documents in regards to her marriage with Allan, and their ultimate divorce.”

“I wish I would have known the whole story at the time when I was reporting the Kassenoff case,” he said. “But I did not. Now that more facts have been presented to me, I now see where I was wrong.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

While Allan told me he is satisfied that Harvey has apologized, he said the damage has been done. “When the videos first came out, you know, you’re getting hammered left and right. And I don’t even mean death threats. I mean just video after video about you, not just from a TikTok, but articles that did no research.”

Now, he concludes, “the narrative is set.”

We don’t know what happened in the privacy of the Kassenoffs’ home, only that a state court found both parents had caused their kids to suffer. Yet it was Allan who was put through trial by internet, where virality rejects complexity, where the most popular stories are often one-sided, where nobody has an incentive to interrogate the evidence, let alone call witnesses for the defense.

The verdict was resounding: Allan is an evil man who robbed a loving mother of her children.

Allan turns into the driveway of his home in Westchester—a large, wooded structure, held up by stone columns, which his kids joke looks like a haunted house. It feels like one, too. Catherine Kassenoff doesn’t live here anymore, but you can feel her presence everywhere. Pictures of her still hang on the dining room walls; in one, she beams from a hospital bed, holding a newborn child (Allan can’t remember which one). On the mantelpiece in Allan’s bedroom sits a family portrait in a gold frame. The three kids are toddlers, dressed in white tulle dresses, sitting on Allan’s lap. Catherine, statuesque in a strapless white gown, leans over her family, unsmiling but serene.

When I ask him why he hasn’t taken down the pictures, he just shrugs. “She’s still their mother.”

We sit in the kitchen as Allan sips from a cup of black coffee, in between nervously spinning it on the table. The girls are chatting in the next room, but I notice that Allan doesn’t keep his voice low as we speak about Robbie Harvey’s videos and their consequences.

He tells me how, in the past year, he’s thrown himself into life as a stay-at-home dad.

On a school day, he typically wakes his three daughters at 6:45, but always has to go back to check on JoJo, who he jokingly refers to as “Sleeping Beauty.” Afterward, Allan chauffeurs the girls to and from school, and to their various activities—soccer, basketball, ice skating, cheerleading practice.

They seem like a happy family, but their humor is sometimes dark. At one point, I hear the girls bantering about who has the best bedroom: Ally, they all agree. When JoJo complains that hers is too hot, Ally jokes: “At least you didn’t have to sleep on the floor for years.”

At another point, JoJo picks up a bottle and hits her sister, Charley, on the head. Charley squeals, and Ally pipes up: “At least now you know what it feels like to be me.” She then turns to me and asks if I’d heard the story of when her mother threw a glass at her.

Allan didn’t seem to mind my asking the girls questions, claiming they have “no privacy anymore thanks to Harvey and Catherine.” But all three were reluctant to talk about their mother, often changing the subject when I brought her up. When they do reference her, they refer to her as “Catherine.” When I ask if they miss her, all three girls reply with a resounding “no.”

Allan is worried their lifestyle could soon drastically change. Since he was forced to resign over a year ago, he says he has applied to around 70 jobs, but hasn’t received a single offer. His severance package has run out, he tells me, and he will have to sell the house if something doesn’t come along. He signed up for unemployment benefits, but when prompted to explain why he left his last job, he didn’t know how to answer.

“There’s no option for ‘a TikToker destroyed my career,’ ” he told me.

He said he doesn’t blame employers for not wanting to hire him: “This guy spread the gospel of me being the devil.”

In his lawsuit against Harvey, Allan alleged that the TikToker directed his followers to harass him, and intentionally sought to get Allan fired from his job. He also claimed that Harvey’s “motivation was one thing and one thing only—money.” He pointed to a now-deleted Facebook post—in which Harvey says he’s built a “movie room” with “surround sound”—as evidence that the TikToker was “apparently proud of the money he made off of the children’s suffering and trauma.”

Whether you believe Allan was an abusive husband or the victim of a manipulative wife—or something in the middle—it’s hard to deny that, since the dawn of social media, “suffering and trauma” have become a valuable resource: the best way to get attention, which is what makes money on the internet.

But Allan says “the few seconds of me telling Catherine I hate her” wasn’t what ruined his life. He regrets his behavior; but, he says, “tell me who wouldn’t look bad if their worst moments in time were recorded?”

“I think the issue is Robbie Harvey’s story,” he says. “You know, his version of reality.”

In this version, Allan is a monster—and he’s not the only one. In the role of Catherine’s avenger, Harvey called upon his TikTok followers to go after other people who supposedly betrayed her: Carol Most, Susan Adler, Marc Abrams. All of them told me they received death threats as a result.

Carol Most played me an audio message in which a woman says, “Bitch, you are lucky I don’t live in your same state or else I’d find where you live and slit your fucking throat.”

Susan Adler, the children’s therapist, showed me various abusive emails, including one that read: “We are coming for you. Coward. Prepare to die,” and another that stated, “Die, bitch. Die painfully. Cunt.”

“That anybody could think I was such a horrible person when all I did was care about their children,” Adler told me, “was horrendous.”

Marc Abrams, meanwhile, has received “thousands of nasty messages, nasty texts, nasty emails and death threats” since Catherine’s death.

“It really doesn’t matter what the truth is,” he told me. People on TikTok don’t want to “explore what may be fact as opposed to fiction.”

They “simply hold you guilty.”

Robbie Harvey’s early posts, which date back to 2021, are mostly geared toward men, who he coaches to “choose to be attracted to your wife” and to do simple tasks for their spouses like taking out the trash and “stop watching porn.” But he also comments on cases where men have allegedly abused or acted inappropriately toward women, sometimes calling out these husbands by name.

Sometimes he alludes to the idea that he’s prosecuting—rather than documenting—a case. In June 2023, when a TikTok user asked about all the people who had allegedly failed Catherine—“how do we bring them all down?!?!”—Harvey responded: “I’m working behind the scenes.”

“Many of you have asked, ‘If we get justice for Catherine Kassenoff’s death, then what will happen to the kids?’ ” he says in a video from July 9, 2023. “Many of you have asked, ‘Am I adding to their trauma?’ ”

Instead of answering, he criticizes the family courts that “sell children to the highest bidder—just like Allan Kassenoff.”

It’s a good question, though: Did Robbie Harvey and the social media firestorm add to the girls’ trauma? Jennifer Voltz, the waitress at the diner where they used to wait to see their mother, tells me that as the story of their parents’ divorce has taken on a life of its own, the kids—now 10, 13, and 14—can’t escape it. They’re just “trying to figure out who they are,” she says, but “they’re getting bullied at school”—partly because the man who picks them up after class has been demonized online.

Voltz believes Allan “didn’t do anything wrong.” But she also believes the real story is probably much more complicated than anyone knows.

“You have three sides to every story,” she said. "His, hers, and the truth.”

VIII. ‘Her Dying Wish’: The Haunting of Allan Kassenoff

It’s been more than a year since Catherine emailed her suicide note, but Allan isn’t yet convinced she’s dead. Although he received her death certificate from both the Swiss authorities and the U.S. Department of State, dated the same day her suicide email was sent, he still can’t talk about her death without prefacing it with the word alleged.

According to her U.S. death certificate—which Allan showed to me—Catherine’s body was cremated, and her ashes are in the custody of Wayne Baker, who has stopped returning my calls.

I last saw Allan at the Starbucks in a Westchester train station, in mid-March. He had his brown accordion file folder with him, and as we talked about Catherine, his voice grew louder, almost enthusiastic. He leaned over the table between us and started to pull out his wife’s bank statements.

Allan is obsessed with trying to understand Catherine’s last moves. He told me he had scoured her financial records for months, trying to work out what happened to her assets. He has theories even he admits are wild. He sometimes says, half-jokingly, that he thinks his wife is alive and well, living in France.

In Catherine’s will—which Allan also showed to me—she left what remained of her assets to her children, but Allan says her executor is in control of them. “Wayne Baker could do anything he wants,” he claims. “One thing you could do with [the assets],” he speculates, is “send someone who’s living overseas who is undercover money.” (There is no evidence that Baker has used any of the money in Catherine’s estate inappropriately; when I tried to contact him, to ask about Allan’s suspicions, he did not respond.)

The Kassenoffs’ divorce was never finalized, and Catherine’s will emphasized: “I intentionally make no provision for Allan Kassenoff, for reasons best known to him.”

But Allan is now fighting Baker in court for 50 percent of the estate—for the sake of the kids, he says. It seems that neither he nor Catherine saw her suicide as the end of their divorce: Allan also showed me a letter of instructions Catherine wrote to Wayne Baker, in the event of her death—in which she directs her lawyers to continue pursuing a lawsuit against Allan.

“Assuming she’s dead,” Allan says—a caveat I’ve heard him use multiple times—“her dying wish and goal was to still hurt me and the kids.”

For the past year, Allan’s had to live with constant death threats. He scrolls through his inbox of Facebook messages in front of me—he’s received around 1,600 in the last year, he says—and what I see is an almost hourly barrage of hate mail: people calling him a “disgusting human being,” telling him “can’t wait to spit on your grave,” and “I hope you pay for this for the rest of your life.”

On that last afternoon in Westchester, he told me he thought this was what Catherine would have wanted. “She set this all in motion,” he says, in a tone that suggests there’s no doubt in his mind. “Whether she got lucky with Harvey picking this up, or she coordinated with him, either way: this is her dream.

“It’s like she’s harassing me from beyond the grave.”

Francesca Block is a reporter for The Free Press.

Deep investigations take time. To support our work, become a Free Press subscriber today:

Well, a good read for dads involved in custody disputes….when you think your situation is the worst, someone will outdo you by an order of magnitude!

My guess is that this story is far from over. Stay tuned.

My money is on her being alive and well. I find it curious that the reporter couldn’t nail down the cancer diagnosis or recurrence…