The Free Press

On November 8, 2021, a college professor named Pano Kanelos set off what felt like a bomb in these pages when he announced that in a country with more than 4,000 colleges and universities, he was moving to Austin, Texas, to start a new one.

“We are done waiting. We are done waiting for the legacy universities to right themselves. And so we are building anew,” Kanelos wrote. “I mean that quite literally. As I write this, I am sitting in my new office (boxes still waiting to be unpacked) in balmy Austin, Texas, where I moved three months ago from my previous post as president of St. John’s College in Annapolis.”

(Read the original piece: We Can’t Wait for Universities to Fix Themselves. So We’re Starting a New One.)

Many people said it was impossible. But yesterday, less than three years after that original essay, the University of Austin opened its doors to the class of 2028.

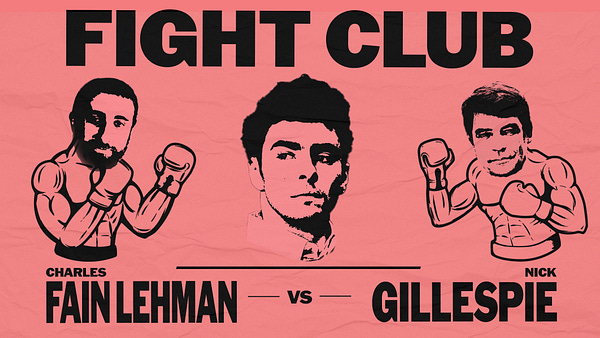

I cannot claim objectivity on this subject: I have been part of UATX, along with Kanelos, Joe Lonsdale, and Free Press columnist Niall Ferguson, since its inception. (This is the talk I gave at the inaugural summer school.) I am so proud of what the school is—and more, what it aspires to become. I think you’ll understand why when you read Pano Kanelos’s convocation address to the founding class, published just below.

In an era of so much brokenness—and it’s hard to think of an area of American institutional life more degraded than higher education—sometimes the only thing to do is to begin again. —BW

Good morning. It is a sincere pleasure and profound honor to welcome you to the inaugural Convocation of the University of Austin.

We often hear of occasions referred to as historic. Usually this is a sort of feeling or sense that a particular moment or event is elevated or heightened, that something noteworthy or novel is occurring—a new this, a first that. This to me seems a rather tepid use of the term historic.

What is truly historic is that which sends the trajectory of history, and lives lived within the stream of history, shooting in a direction other than that toward which they were tending. History is not a story unfolding; it is an epic being written. And its authors are those bold enough to exercise their agency in the pursuit of higher things.

As I look across this room, I do not see students or faculty or staff or loved ones. I see a room filled with the courageous, the bold, with pioneers, with heroes. I see a room filled with those who have said, emphatically, we will not accept passively what we have been handed, the givens are not good enough, we will create anew. We have come together, all of us, as founders.

Ours is a revolutionary institution—revolutionary in the proper sense. False revolutions propose only the tearing down of the established order; they are an exercise in nihilism. Yet the word revolution—in its original sense, revolvere—means to revolve, to turn back to a point of origin, with the purpose of renewing an original spirit or ideal.

To what are we returning? Not to some pallid vision of what universities looked like a decade or two or three ago, before their current malaise. Not to some nostalgic notion of ivy-covered quads and fusty dons. Our return is even more radical, radical in the sense of radix, roots, in that we are returning to the very roots of the Western intellectual tradition, to the very roots of the civilization that brought forward these extraordinary institutions called universities.

We are returning to a time when living the life of the mind was itself a bold adventure, when the world was afire with contending and clashing ideas, when everything under the sun was scrutinized, and measured, and queried, which gave birth to a civilization that was restless, and curious, and risk-taking, a Promethean civilization that sought the light of truth, even when that light was searing or sometimes even blinding.

Higher education is often referred to blandly as the “academy” or “academia.” This occludes how extraordinary the original Academy actually was. In 387 BC, Plato, very much like we are doing today, founded a school, which took its name from the place where it met, an olive grove on the fringes of Athens called the Akademia. Here, the great philosopher gathered students who were passionate about pursuing the fundamental human questions: What is justice? How do we acquire knowledge? What is the source of beauty?

There were other schools in Greece that coalesced around such figures as Empedocles, Epicurus, Thales, Democritus, and many others, all of whom believed that the world could be understood through sustained rational inquiry, and each of whom offered particular answers to the mysteries of the cosmos.

What distinguished Plato’s Academy, however, was doctrinal pluralism and a variety of intellectual approaches. There were no easy answers. Every discussion branched outward with ever-greater complexity. The Academy did not commit to a particular school of philosophy, but was a place where knowledge was comprehensively debated, analyzed, and advanced; it was, in the words of Shakespeare, the “quick forge and working house of thought.”

The range of topics was vast, the curiosity of the students ardent, their appetite for ideas voracious. From just a selection of the works of one of Plato’s students, Aristotle, we can come to understand how wide-ranging were the intellectual concerns of the age: On the Heavens, Meteorology, On the Soul, On Memory, On Sleep, History of Animals, Movement of Animals, On Colors, The Situations and Names of the Winds, Metaphysics, Ethics, Politics, Economics, Rhetoric, Poetics. Plato and his students were not narrow specialists, not pedants, not ideologues; they were rather propelled to dispute, to discover, everything there was to know, and to test the boundaries of knowing itself.

The animating spirit of the Academy was Plato’s great teacher, Socrates. Socrates was famous, perhaps infamous, for engaging the citizens of Athens in frank conversations about philosophical topics. He was restless, persistent, infuriating. He cornered his fellow Athenians and pressed them to answer his questions: Is virtue taught or does it come to us by nature? What is the purpose of love? Is the soul immortal?

As each would offer a response, Socrates would push harder, “Is this truly the best answer?” His persistence did not make him popular, and he was ultimately put to death after trial by his fellow Athenian citizens. Yet his mode of inquiry, the Elenchus or Socratic Method, is the fountainhead of the entire Western intellectual tradition.

“Is this truly the best answer?” This turn of mind, this unalloyed commitment to truth-seeking, which takes both humanity’s passion for understanding along with the realization that, as individuals, our capacity to apprehend what is true is limited, this is the very reason we create these collective enterprises known as universities; it is why this university is dedicated to the fearless pursuit of truth.

Sacred institutions rest upon the revelation of settled truths, truths from the mouths of prophets and from the pages of hallowed texts. For human institutions engaged in human matters, however, given that, as Kant opined, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made,” our confidence in received opinion ought to be tempered. Our work is to stir up settled ideas, not as puerile exercises in contrarianism, but to see if, once they settle back into place, they have the same shape as before.

The term education derives from the Latin educare, and means “to lead out of.” To lead us out of what? Out of ignorance. A liberal education is one that presumes that human beings have freedom and agency, and that in liberating us from ignorance we will learn how to use our freedom well. Its purpose is not simply knowledge, but wisdom.

The great cautionary tale in the West is that of Doctor Faustus, who sold his soul to master every area of knowledge—law, medicine, theology, philosophy—but who, with all the power in the world at his fingertips, could think of nothing better to do than to satisfy his most trivial desires, and he surrendered his life at the allotted time in despair. His tale is tragic. Knowledge without wisdom is enslaving. Faustus had limitless knowledge in every domain. But he failed to come to know himself, and in the end was struck down by his own pride.

This is the great insight of the Western tradition, that all knowledge begins with self-knowledge. “Know thyself”—Γνῶθι σαυτόν—proclaimed the Oracle at Delphi. We must brush away the veils, dispel the shadows, unshackle ourselves from the chains of ignorance, beginning within and working ever outward.

Francis Bacon, the great Renaissance statesman and father of the scientific method, understood the manifold ways that humans compound our ignorance. He identified four “idols,” or false images, that distorted our understanding of the world. Looking at each in turn, we can come to understand the mission of a liberal education and perhaps come to understand some of the pathologies that afflict our own culture and society.

The Idols of the Tribe represent our tendency to leap to conclusions that accord with our desires, to ignore evidence that countermands our prejudices. To remedy this, we should seek objectivity, to see the world as it really is.

The Idols of the Cave reflect our limited, often warped, perspectives; what we know of the world is circumscribed by our narrow experience and often arbitrary circumstance. To remedy this, we should seek to be intellectually expansive, to search for sources of authority outside ourselves or those we have inherited.

The Idols of the Marketplace are those that arise from confusion in human communication, largely out of the imprecise nature of words and symbols and our failure to agree on common meaning. To remedy this, we should lead with empathy and grace, seeking to master the art of dialogue.

Finally, the Idols of the Theater are those errors that arise from the totalizing theories and abstract formulations that we construct to explain the human experience. To remedy this, we should embrace intellectual humility, rightly sizing the scope of human ambition, and be wary of those who claim to have found all the answers.

Universities, like Plato’s Academy, are the places that we have dedicated to these very ends: Seeing the world clearly, seeking to be intellectually expansive, learning from one another through conversation, asking fundamental questions. The word university comes from the Latin universitas, or a community convened toward a common end. As we pursue this common end, a quest for clarity that is often elusive, we must remember that each of us has only a fragmentary understanding of the world, that each of us, at best, adds a small piece to the great mosaic of learning.

Intellectual humility is not fashionable. Nor is the passionate pursuit of truth. We live in a schizophrenic age. On the one hand, this is the Age of I, an age of solipsism, of narcissism; we are so ensorcelled by the idea that the self is primary and inviolable that we have collapsed into nihilism. On the other hand, this is the Age of Ideology, a time when a regnant and totalizing system of thought, grounded in the fundamental error that all human relations are exclusively relations of power, is ascendant; we find ourselves stranded in a stark landscape, where the bellum omnium contra omnes, the war of all against all, rages, only to be mitigated, we are told, by the imposition of a technocratic, censorious, and absolute Leviathan. Our institutions, including our institutions of higher learning, have been overwhelmed by both the relativism of the Age of I and the absolutism of the Age of Ideology. They are shaken, unsteady, adrift.

So let us begin again. Let us be revolutionaries, radicals, returning to the headwaters of our tradition, reviving the spirit of curiosity, of courage, following the great chain of conversation across the ages, where orthodoxy and heterodoxy contend, carried out in books, in works of art, in the progression of the sciences. Our university, like Plato’s Academy, is a sort of sacred grove, a place set apart, from which we can observe the vicissitudes of our times, but not become enslaved to them. Let us ask, again and again, “Is this the best answer?”

From these humble beginnings, if we embrace the simplicity of our purpose and the clarity of our mission, becoming ourselves pioneers, founders, mavericks, and heroes, bringing into to the world not only this institution but also the remarkable things that we will each build, create, fashion, and forge, we will indeed look back at this moment, at this occasion, as truly historic.

So let us begin. Convocatum est!

Follow along with the founding class—and don’t miss a thing—by subscribing to Inside UATX. If you’re reading this and wonder how you can support this new school, please click here.

I wish them great success.

And I would like to point out some errors that I have detected while browsing through the web site.

Errors in “Select Core Texts”:

- The Travels of Ibn Battuta is a work by Ibn Battuta. Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier on February 24, 1306. It is not a work of Thucydides.

-Nicomachean Ethics, Physics y Politics are works of Aristotle. It is not a work of Aeschylus.

Review the entire website.

Forgive my possible mistakes. I am writing using a translator.

Thank you

Enrique Herrera. España

I wish your university the greatest of success.

I only wish we had something similar in woke, broke Australia.

We have so many bright, innovative, thought-diversity champions of the minds down here.....with no where to go.

Your moral courage - Pano, Bari, Joe, Niall, and team - is invaluable to the world.